Eastern Orthodoxy

The Historical Context

In our introductory class last week we focused on Eastern Orthodoxy today – meaning what did it look like today, the basic demographics – where it was primarily located, and what modern countries have the most Orthodox adherents.

We are going to make a big shift today and go from today to the beginnings – that is the beginning of the Empire and the beginnings of Christianity. There is a lot of history to cover, about 18 centuries. But we are going to try to focus primarily on the history as it pertains to the eventual evolution of the strain of Christianity known as the Orthodox Catholic Church.

31 BC – the end of the Roman Republic and beginning of the Roman Empire

Julius Caesar’s nephew became the first Roman Emperor and took the name Augustus Caesar.

Augustus ruled from 31 BC until 14 CE and is still considered one of the greatest of all the emperors.

His rule and the first 200 years of the Empire is referred to as Pax Romana (Roman Peace). It was the period of greatest growth of the Empire.

Roman politics made our inept government look exceptional.

One Emperor after another took office, usually following an assassination.

The trick to stay alive seemed to be to keep the Senate, the Pretorian Guard, the Roman Legions and their top generals happy.

Roughly, from the death of Augustus Caesar in 14 AD to Emperor Diocletian in 287, a period of 270 years, there were 48 Emperors, and 29 of them were assassinated, and four of them committed suicide, possibly to avoid assassination. So only 16 of them left office in a peaceful way.

So let’s jump past all of that intrigue and look at what the early Empire looked like in what is considered its peak year 117 AD.

This is a map of the Early Roman Empire at the height of its power in 117 AD. It covered a vast territory and is considered the largest political and social structure in Western civilization. They divided the territory into provinces, as shown and extended from near the top of Britannia on the north, Mauretania on the west, Egypt on the south, and Mesopotania or Armenia on the east.

While we are looking at it let’s note some other things. Note that Rome is not at the center of the Empire. More importantly, but not evident from the map Rome is far from the center of wealth in the empire. At this point in time there were numerous larger cities in the east that were much wealthier than those in the east. So Rome was not near most of the wealth it controlled. As we discussed when we covered the Reformation era, there were not that many large cities in the Western part. of Europe. Places like Spain France and Britannia were largely rural.

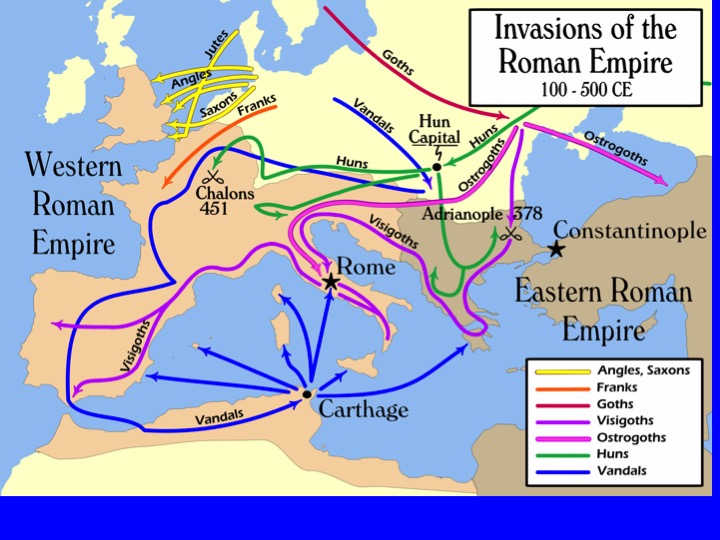

The other thing to note is the looming menace hanging over the western part of the empire called Germania Magna. This is the home of the Germanic tribes that you have heard so much about. You know, the Goths, Visagoths, Huns, Franks, Vandals, Ostrogoths, etc. The movement of these tribes and others into the western Empire can best be understood as part of what European historians call The Migration Period.

The Migration Period was a time of widespread migrations within or into Europe in the middle of the first millennium AD. It has also been termed the Barbarian invasions. Many of the migrations were movements of Germanic, Slavic, and other peoples into the territory of the then Roman Empire, with or without accompanying invasions or war.

The Migration Period was a time of widespread migrations within or into Europe in the middle of the first millennium AD. It has also been termed the Barbarian invasions. Many of the migrations were movements of Germanic, Slavic, and other peoples into the territory of the then Roman Empire, with or without accompanying invasions or war.

The migrants comprised war bands or tribes of 10,000 to 20,000 people. The first migrations of peoples were made by Germanic tribes such as the Goths (including the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Anglo Saxons, Lombards, Suebi, Frisii, Jutes, Burgundians, Alamanni, Scirii and Franks; they were later pushed westwards by the Huns, the Avars, the Slavs and the Bulgars.

So these movements of peoples were perhaps more migrations then invasions, although the migrations often turned into wars because the Empire tried to keep them out. They were a growing major problem to the western empire. Over time though they absorbed into the culture and in fact became significant parts of the Roman legions, often led by German generals.

So, over time, three crises threatened the Roman Empire: external invasions, internal civil wars and an economy riddled with weaknesses and problems. The city of Rome gradually became less important as an administrative center.

Emperor Diocletian (284 to 305 CE) believed that the empire was too big for one person to rule and divided it into a tetrarchy (rule of four) with an emperor (Augustus) and a co-emperor (Caesar) in both the east and west.

This did not go well. The western Emperor died and his Caesar young Constantine rose to power. Diocletian (Eastern Emperor) did not like that and nominated Maxentius to be the western Emperor.

The ambitious Constantine, supported by his Roman legions, challenged and defeated Maxentius at the battle of Milvian Bridge, becoming the sole Emperor of the West.

When Diocletian inexplicably decided to retire, his replacement Lucinius assumed power in the east in 313 AD and Constantine challenged and defeated him at the Battle of Chrysopolis, reuniting the empire in 324.

Constantine announced almost immediately that Rome could not remain the capitol of the empire.

Rome’s economy had stagnated and it’s infrastructure was in decline.

He choose to build a new city at the site of old Byzantium, and name it Nova Roma (New Rome).

The site was closer to the geographic center of the Empire and more importantly closer to the wealth of the Empire.

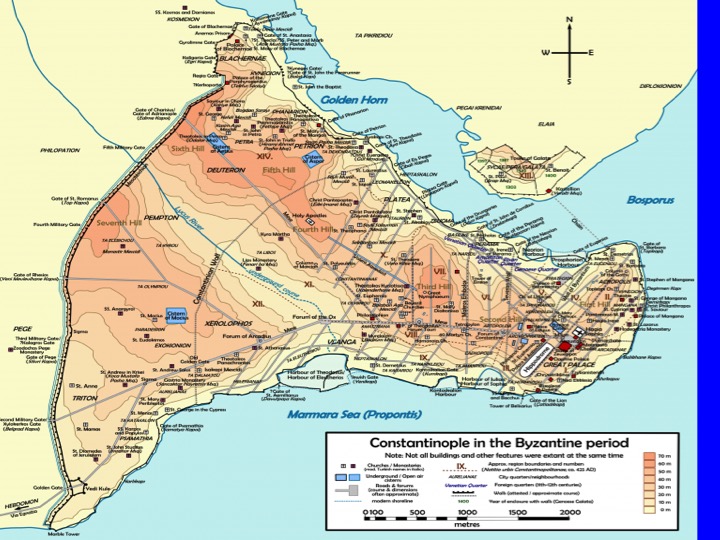

Surrounded by water, it could be easily defended. Had an excellent harbor, and easy access to the Danube river and the Euphrates frontier

Although he kept some remnants of the old city, New Rome --four times the size of Byzantium-- was said to have been inspired by the Christian God, yet remained classical in every sense. Built on seven hills (just like Old Rome), the city was divided into fourteen districts. Supposedly laid out by Constantine himself, there were wide avenues lined with statues of Alexander the Great, Caesar, Augustus, Diocletian, and of course, Constantine dressed in the garb of Apollo with a scepter in one hand and a globe in the other.

In 330 CE, Constantine consecrated the Empire’s new capital, a city that would one day bear the emperor’s name. Constantinople would become the economic and cultural hub of the east and the center of both Greek classics and Christian ideals. Its importance would take on new meaning with Alaric’s invasion of Rome in 410 CE and the eventual fall of the city to Odoacer in 476 CE. During the Middle Ages, the city would become a refuge for ancient Greek and Roman texts.

With the move of the government of the empire to Constantinople the nature and culture of both the government and the church changed dramatically. Although the official government people called themselves romans and Constantinople was frequently referred to as the “Second Rome”, this became in many ways a Greek government.

Constantine died in 337 AD, after 30 years of service, but left his successors and the Empire in a typical Imperial turmoil.

There follows a long history (another 1100 years) of the Eastern Empire.

But we will now turn to how this move of the capital to Constantinople and the East played out in creating and spreading the Orthodox Catholic Church in that part of the world.

Another new word for the day – Caesaropapism

Caesaropapism's chief example is the authority the the Byzantine (East Roman) Emperors had over the Church of Constantinople or Eastern Orthodox Church from the 330 AD consecration of Constantinople through the tenth century. The Byzantine Emperor would typically protect the Eastern Church and manage its administration by presiding over Ecumenical Councils, appointing Patriarchs and setting territorial boundaries for their jurisdiction. The Emperor exercised a strong control over the ecclesiastical hierarchy, and the Patriarch of Constantinople could not hold office if he did not have the Emperor's approval.

It is important to remember that all through European history there has been a strong understanding by kings, emperors, and others in high office that a strong state religion can be the glue that holds the kingdom or Empire together. Consequently the rulers across Europe have taken a keen interest in religion, and particularly on the predominant religion of their country or Kingdom. Often supporting that predominant religion and suppressing other religions.

It is important to understand though that although Caesaropapism certainly existed to a certain degree many influential church leaders opposed it constantly.

So how did all of this work?

So how did the church do?

Eastern Orthodoxy spread throughout the Roman and later Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empires and beyond, playing a prominent role in European, Near Eastern, Slavic, and some African cultures.

During the first eight centuries of Christian history, most major intellectual, cultural, and social developments in the Christian Church took place within the Empire or in the sphere of its influence, where the Greek language was widely spoken and used for most theological writings.

Between 325 and 787 AD seven influential councils were held, targeted at defining the faith and eliminating various heresies.

Every one of them was held in the Eastern part of the Empire and was conducted in Greek with Eastern Bishops and Patriarchs leading the arguments. The Pope of Rome never attended these councils.

Yet all of the decisions of all of these councils are still today accepted by both the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox church.

But now we are going to turn to the initial question raised in the beginning of this class. How did this early development of the Roman Empire and church lead to today’s arrangement of a church that is predominately in one part of the world, primarily Eastern Europe, and still a strong established Christian denomination.

First – who are the Slavs?

Slavs are the largest Indo-European ethno-linguistic group in Europe. They are native to Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, Northeastern Europe, North Asia, Central Asia and West Asia. Slavs speak Slavic languages of the Balto-Slavic language group. From the early 6th century they spread to inhabit most of Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe.

States with Slavic languages comprise over 50% of the territory of Europe, therefore it is the largest ethno-linguistic group in Europe by land area. Present-day Slavic people include for example, Belarusians, Ukrainians, Russians, Serbians, Bulgarians, and Macedonians. It is noteworthy that each of these countries appears in the list I presented last week of countries that are predominately Orthodox (more than 50% of the population).

And yes – there is a story there.

In the ninth century two brothers from Thessalonica initiated mission work to the Slavs. Cyril and his older sibling Methodius. They are now referred to as “the apostles of the Slavs.”

They were both highly educated, and were monks of the Eastern Orthodox church.

In 860–861, the brothers went on a diplomatic mission to the Khazars (north of the Caucasus) and, while there, learned the Slavic language, which importantly, as yet existed only in speech, not in writing.

In 862, the emperor Michael III sent them to Moravia (a territory east of the present Czech Republic), where they began to teach in the vernacular they had earlier learned.

Cyril then decided that the Slavic languages needed an alphabet so that Christianity could be spread through Bible written in Slavic tongues. Cyril invented the Glagolithic alphabet (Cyrillic), which became the medium for the translation of the Bible into Slavic and the development of a substantial ecclesiastical literature in Slavic.

Cryllic is the basis of alphabets used in various languages, past and present, in parts of Southeastern Europe and Northern Eurasia, especially those of Slavic origin, and even in non-Slavic languages influenced by Russian. As of 2011, around 252 million people in Eurasia use it as the official alphabet for their national languages. About half of them are in Russia. Cyrillic is one of the most-used writing systems in the world. And as people learned to write with this new language the reading material they had was the Slavic translations of the Bible provided by Cyril.

Thus the Slavic people were often exposed to Christianity exclusively through the church's established in the East (Constantinople being the first). There was little competition from other religions.

Christianity took a firm hold in the Ukraine and Russia through the grand prince Vladimir (d. 1015), who held sway over those lands. Adopting Orthodoxy, he subsequently imposed it on the territories he had conquered.

From that time forward the relationship of the Russian patriarch in Moscow and the czars (“Caesars”) mimed the dance of caesaropapism characteristic of Constantinople.

Orthodoxy was able both to survive and thrive in these Slavic lands and escape the vigorous attempts at conversion by both the later Roman Catholic church and Islam.

The East–West Schism, also called the Great Schism and the Schism of 1054, was the break of communion between what are now the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches, which has lasted since the 11th century.

The break was not sudden. There was a growing series of disagreements on theological and ecclesiastical issues that went on for several centuries.

Some of the issues: the source of the Holy Spirit, the authority of the Pope, whether leavened or unleavened bread should be used in the Eucharist, etc.

Next Week

We have talked about Holy tradition and the importance of the liturgy in keeping the tradition.

Next week we will explore that and try to experience what the ancient and extensive Orthodox rites are and how they are used in worship.

And in doing that we will review some of the basic beliefs and practices that set the Orthodox tradition apart from other Christian denominations.

< Audio >