Christianity in the Reformation Era

Early Modern Europe

Early Modern Europe - A Larger View

In the period from c. 1500 to c. 1650, modern Christian pluralism took shape in Western Europe. Catholicism persisted and was renewed; various forms of Protestantism were born and institutionalized; and a wide range of radical forms of Protestantism emerged. We will attempt to understand each of these strands on their own terms and in conflict with one another. And try to provide an international perspective on early modern Protestantism, radical Protestantism, and Roman Catholicism in their complex social, political, and cultural contexts. We will then discern how their differences and conflicts contributed decisively to the emergence of modern ideas and institutions.

The Approach

• We will emphasize a cross-confessional story.

• Note the title – “Christianity and the Reformation Era”.

• What actually emerged was a renewed Catholic church, as well as various forms of Protestants, and a variety of radical Protestants.

• We will try to understand Protestants, Catholics, and Radical Protestants – each on their own terms.

What does that mean? Until the last two decades almost all histories of the Reformation Era were confessional. A confessional history is one written from the perspective of one church. The majority of scholarly histories until very recently) of the Reformation were frankly written by Protestant scholars, with some minority ones written by Catholics and very few by Anabaptists. Confessional histories tend to be about who were the good guys and who were the bad guys. In particular Protestant Confessional Histories tended to follow a narrative of a corrupt and evil Catholic church that was superseded by a reformed and enlightened movement that finally gave people the freedom to worship as they pleased. Although it is easy to say today that people can worship as they please in some societies - in fact freedom of religion was a very foreign concept in the Reformation Era - none of the protagonists, Reformed or Catholic had freedom of religion as a goal. It was in fact a very foreign concept. We will learn just how foreign as we progress through the classes. We are going to strive instead to be cross-confessional. Emphasizing how each of the traditions interacted with each other without being judgmental about any of them.

In fact you will note that I choose the title carefully. It is not called the Protestant Reformation. It is about the Reformation Era - which involved many reformations.

By many reformations we mean the emergence of a reformed Catholic church as well as various forms of standard Protestants and a variety of Radical Protestants.

And we are going to strive to understand each on their own terms - so that if they were here they might recognize we were talking about them. So I will be repeatedly putting on and taking off my Catholic, Protestant, and Radical Protestant hats as I present their conflicting stories.

In doing this study we will run into difficulties in trying to understand what people were thinking.

The first difficulty is what I call the Otherness of the time. In studying 16th century people we are dealing with a culture that is 5 centuries before ours. If we try to judge the 16th century by ours we will never understand. It is easy for us to be offended by 16th century views of things like society hierarchies, like gender relationships, beliefs about religious freedom. But we have to remember that most of these views were shared by all of the participants. Catholic and Protestant.

Secondly – in our modern separation between church and state we also live in a world of religious versus secular in daily culture and we come to view that as normal. But Christianity in the pre-Reformation period, unlike today, was deeply embedded in all aspects of human life, including both political and social life. And we will try to understand the implications of that. As an example of that we will frequently talk about the secular political structure in the various countries, like mayors, city councils, Princes, nobels, and even Kings. But every one of these were all Christians and they often were making religious decisions for their cities or regions.

The third thing that makes the story complicated is that religious changes played out very differently in different contexts. The Germanic countries had different experiences than in France, or Italy, or Switzerland. So as we tell the story we will have to jump around and talk for instance about what the Calvinists were doing in Germany – we may find that the Calvinist experience was very different in France, or the Low Countries, or in England.

As a general outline the presentation combines a largely chronological ordering with analysis and organization that shifts depending on the subject matter of each lecture. We will attempt to do this chronologically, but the complexity of the story will require constant jumps back in time to discuss the different traditions. We will kick all of this off, as usual, with a review of the contextual broth that that fed Reformation thinking. Because things were already changing on the eve of the Reformation era.

Let’s begin with I call the Landscape of Early Modern Christianity. We will never understand the Reformation Era if we look at it with 21st century eyes. Thus we will have to try to put ourselves into the worldview of 16th century Christendom.

So in order to try to do that we are going to look today at early modern Christianity in 3 major categories. Demographics - Social Arrangements - and Political Relationships.

The main narrative in understanding the demographics of early modern Europe immediately before the Reformation era was that early modern Europe was very thinly populated compared to today, was predominately agricultural, and that the people were subject to high infant mortality, waves of epidemic disease, and frequent agricultural crises.

65 to 90% of the people were peasants. The 65% referred to the urbanized areas - the 90% to everywhere else - and everywhere else was most of the land mass of Europe.

There were only three areas that might be described as urban in the time before the Reformation. Northern Italy, Southern Germany, and the Low Countries. That was pretty much it.

And you understand I am using the terms Germany in their modern sense. They were not called that then. The term southern Low Countries refers to what we would now call Belgium and the Netherlands.

But over all of Europe there were few real cities. In all of the Holy Roman Empire there were only about 10 cities of over 20,000 people. In France Paris was around 120,000, but the rest of France was rural.

Geographically we will focus on Western Europe – with most of the emphasis on Germany, Switzerland, France, the Low Countries. In the interest of time we will not cover England, even though it’s reformation was rather remarkable.

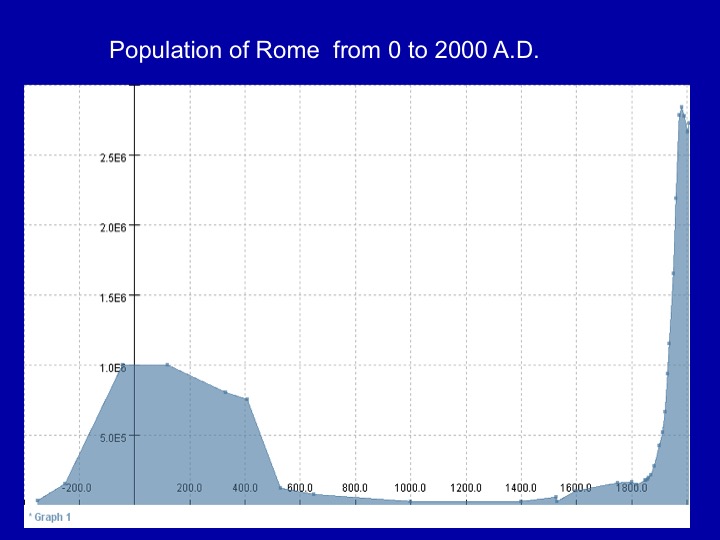

We often think of Rome as a major city, and indeed at the height of the Roman Empire around the time of Jesus it was over one million people. But look at how the population had crashed and how small it was between the years 600 and 1800 A.D.

Some stark realities of Demographics.

Physical suffering and death were persuasive elements of life.

We are reminded of a famous quote from Thomas Hobbes in 1651.

“…. the life of man - solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

The second part of the landscape is the Social Realities. So what were the social realities?

Unlike today when we rather automatically assume that hard work can result in moving on up - this was a society of hard stratification and a rigid hierarchy. And this was reinforced not just by edict - it was by custom and an ingrained habit of thought. You learned from birth what your place was in society and you stayed there. There were a few exceptions to that in some of the urban areas, which I will describe later - but the exceptions were few.

How was all of this held together? There were no police forces and no standing armies - so it was not by force. Rather the higher levels of society used just the right level of paternalism and gifts to the lower levels accompanied to a great deal of deference shown by the lower to the higher. And the combination, along with a constant appeal to the common good was a sort of glue that held society together - most of the time.

These hierarchical arrangements were somewhat different in rural and urban areas and we are going to talk about that.

In rural areas the fundamental hierarchy was between the peasants - the lower - and the lords - the landowners. Some descriptors you should know - the term lords or the term nobility refers to the wealthy families that had been granted the rights to large agricultural holdings in the past and generally kept those rights. They were able to accumulate wealth over time from the land - after all the principle source of wealth was agricultural. The peasants were allowed to live on those lands and worked the lands for the nobility and it was well understood that the nobility were the masters.

I should also add that in addition to the lands of the nobility there were rather extensive agricultural ventures on the larger monasteries. And they also used peasants for the hard work.

Finally the towns were also socially stratified by status and by wealth - but in a much more complex way.

With respect to the rural areas - For those who survived the plagues the century after the Black Death (1350-1450) was actually the best of times for medieval peasants.

And the reason was that the Black Death made agricultural labor much scarcer, giving surviving peasants more bargaining power over noble landowners. Then after 1450 rapid population growth allowed nobles to once again force peasants into a lower standard of living again leading to growing tensions.

The urban areas were also hierarchal, but in a more complex way. The important thing to realize is that in the urban areas there was a large mercantile class that manufactured and sold goods to others. An example was a large woolen clothing industry in northern Italy, especially Florence.. They bought wool from England and shipped it into cities like Florence where it is estimated that 30% of the population was involved in woolen clothing manufacture. Supporting these industries was a flourishing banking industry led by the Medici family.

These wealthy patricians and merchants were at the top of the social hierarchy. One rung below was the urban professionals , for example lawyers and doctors. Then members of the craft guilds. This would be crafts like cobblers, butchers, carpenters, etc. We will have more to say about the guilds when we talk about the political relationships. Domestic servants were a large working class. They lived in the homes of the wealthy. This was the predominant form of work for young unmarried women and they would continue working there until they either married or joined a convent. Finally wage laborers, who worked in the industries.

Then were the homeless. It is not just a 21st century issue. They lived on the street and lived by begging and their wits.

Now - all of these levels of society lived together in rather small towns surrounded by stone walls for defense. So every day the wealthy and the urban professionals rubbed elbows with the working class from the guilds, with domestic servants, with wage laborers, and with the homeless. There were no gated communities outside of town.

I might mention that in the urban areas there was some slight chance for upward mobility. The top people in the guilds might be able over time to graduate to become merchants and move up in class. And really good wage laborers might gain access to a guild - although they had to prove themselves because the guilds maintain their economic strength by controlling the number of guild members in any craft.

Turning to the Political Relationships of Europe at this time - Local urban political institutions were usually mayors and city councils with members from the patrician class as well as members from merchant and craft guilds.

Only male heads of households could participate.

Clergy were exempt from all civic obligations.

Guilds were important parts of the fabric of towns. A typical guild represented a particular craft or a particular group of merchants.

Merchant guilds were formed by the merchants in an urban area for mutual protection of their horses, wagons, and goods when delivering their merchandise.

Craft guilds were groups of artisans engaged in the same occupation – bakers, cobblers, stone masons, carpenters, etc.

Continuing in the rural political relationships - Relations between local and central political authorities were delicate and precarious. Towns fiercely guarded their independence and privileges – central authorities were constantly striving to enlarge their influence.

The largest political institutions were either monarchies (Tudor England) or territorial conglomerates (Holy Roman Empire).

Internationally – there was one major political rivalry in Europe in the early 16th century – the clash between the Holy Roman Empire and France.

Charles V – the Holy Roman Emperor 1519-1556. Frances I – King of France 1515-1547.

O.K. - so we have reviewed the demographics, the social realities, and the political relationships. If you have been listening carefully you may notice we have not talked about religion or Christianity at all.

Now we have to bring Christianity into this story. We said in the previous lesson that Christianity was completely embedded into the matrix of demographics, social realities, and political relationships. Now it is time to talk about how that worked in pre-reformation Europe. We will do that next week.