Genesis Class 4 -

The Ancient Near East

Today’s

class is a natural extension of last week’s material. Last week we covered the biblical history of

the people of Israel from 1400 to 333 BC.

Today we will broaden that considerably geographically and time wise and

try to understand the surrounding culture that the people of Israel evolved

from. If you recall our introductory material from week 1 I mentioned that this

summer we would be attempting to look at Genesis through different lenses than

we normally do. Two of those new lenses will be cultural and literary. Those

two go hand in hand because our predominant means for understanding ancient

cultures is the study of ancient literature. Not only what the literature was,

but how it was understood in ancient times.

And I will say again that we miss a great deal in understanding ancient

literature if we try to read it through modern understandings. So let’s start

talking about the ancient near east and eventually we will talk about it from a

literary standpoint.

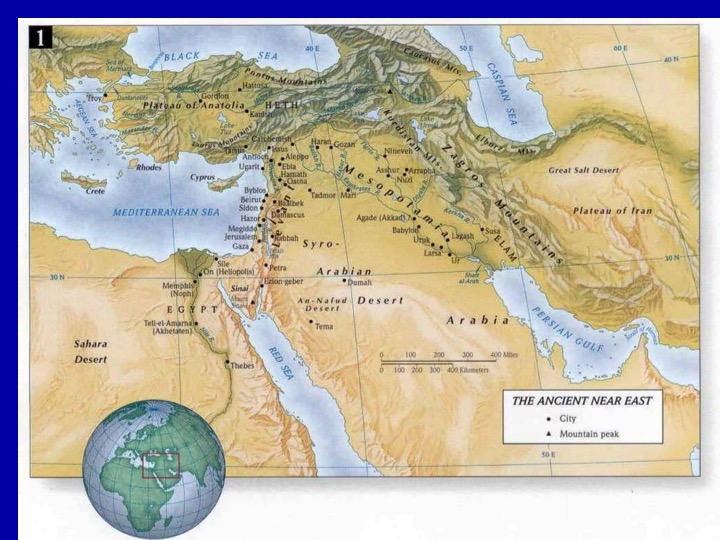

The Ancient Near East is divided into three major geographical regions: Egypt, to the west, Canaan, in the middle, and Mesopotamia, to the east. All of these are important for understanding the Bible in general and the book of Genesis in particular. Why do I say that? Consider this.

The key patriarchs discussed in Genesis are Abraham, his grandson Jacob, and Jacob’s son Joseph. Abraham is born in Mesopotamia, in fact the bible records that he did not leave Mesopotamia until he was 70 years ago. So he was completely immersed in Mesopotamian culture in his formative years. He then migrated to the land of Canaan, and spent time in Egypt during a period of famine.

His grandson Jacob is born in Canaan, but fled back home to Mesopotamia for 20 years, then returned to Canaan and then spends the end of his life in Egypt, where he eventually dies.

His son Joseph is born in Mesopotamia, moves to Canaan with his family at a young age, but then spends his entire adult life in Egypt, where he dies.

So Genesis is a travel tour of the ancient near east.

"Near East" is the term scholars use to refer to the area where Asia, Africa, and to some extent Europe all come together.

Ancient refers to the period from c. 3000 B.C., when our written records first begin, though 333 B.C.E., at which point we move to the Greco-Roman period, also called late antiquity.

From the archaeological perspective, we divide the period into large epochs, Bronze Age and Iron Age, with the former further subdivided into three periods:

Bronze Age (3000-1200 B.CE.)

a. Early Bronze Age (3000-2200 B.C.)

b. Middle Bronze Age (2200-1550 B.C.)

c. Late Bronze Age (1550-1200 B.CE.)

Iron Age (1200 B.CE. onward)

The three main geographical regions of the ancient Near East are as follows:

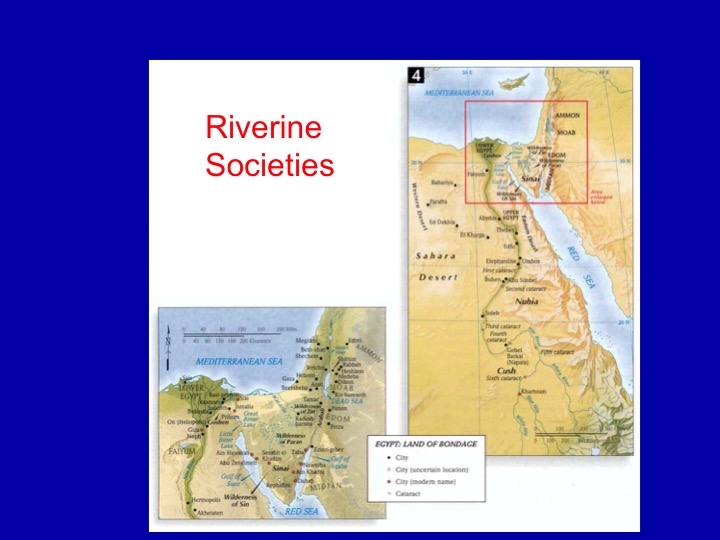

Egypt, which is really the Nile valley, home of the Egyptians, contained mainly a homogeneous population.

Mesopotamia, the Tigris and Euphrates valley, contained, in contrast to Egypt, a very heterogeneous population: it was the home of the Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Hurrians, and others.

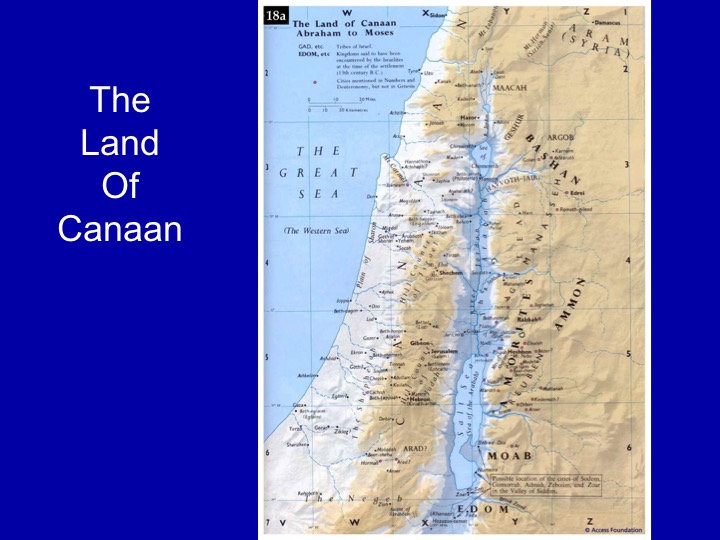

Canaan, the land in between the two great powers listed above, in which lived the Canaanites and the Israelites, might be called "the third world" of ancient times. Canaan has rather amorphous boundaries; basically, we define it as the area bounded by the shore of the Mediterranean to the west and the Syrian Desert to the east.

There are three regions beyond the main Near East that have a role to play in biblical history: Persia (modern Iran), Greece, and Arabia.

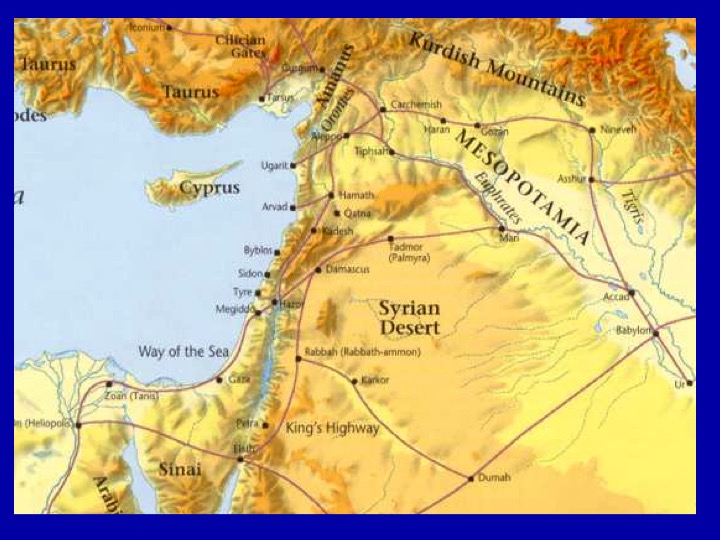

A slightly different view – this time to show the major International travel and trade routes that were in place in biblical times.

One of the important routes was the “Way of the Sea”. This was the predominant route used for travel and trade between Assyria or Babylon and Egypt. The Way of the Sea is mentioned in Isaiah 9:1. The other important one was the “Kings Highway” Linking Damascus south to Elath and on the large oasis of Tema in Arabia or on to Egypt. The Kings Highway is mentioned twice in the book of Numbers.

The point here is again that the people of Canaan did not live in a vacuum – travelers from both Mesopotamia and Egypt traversed through Canaan as part of the economic activity of the times.

We will return to this map in a later class when we examine the question of the birthplace of Abraham.

It is important to note that all of these cultures were literate societies during the biblical period (with the possible exception of Arabia). Moreover, their literary remains often share striking similarities with the Bible, as we have seen already and as we will continue to demonstrate as the course unfolds. Examples include:

By the way – literate does not mean everyone could read – only a few select could read or write anything. And the earliest writing was not literature as we are talking about it – it was primarily economic recordings and later legal recordings.

Let’s talk about why writing probably developed first in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

Let’s mention what drove the development of writing. We will use Egypt as an example but this argument holds for Mesopotamia.

Egypt and Mesopotamia are known as riverine societies. All of the great early civilizations developed along major rivers, particularly in regions where that river was the main source of water. It does not rain much in the ancient near east.

We

have evidence that as early as 4000 B.C. there were organized irrigation

activities along the Nile. As the water

begins to get divided up by irrigation activities the people there have two

options – kill each other for the water – or organize bureaucracies to divvy up

the water. Eventually they get tired of killing each other and government’s

form to manage water. They led to large

urban areas growing around the irrigation – governments eventually take control

and soon they had Pharaohs running the show. Bureaucracies lead naturally for a

need to record information – primarily economic information. And that is what we find in the very early

forms of writing – tons of writings recording economic and later legal stuff.

Literature - as in poetic and prose

narratives – came sometime later.

With that background of writing in riverine societies – let’s talk about the Land of Canaan. The Jordan River is not the Nile. And there is no evidence that it was ever used for irrigation. The people in the Land of Canaan depended on rain water for their crops – and for drinking water they dug wells or when they were luck discovered springs.

As a result all water was local and the result was no major metropolitan areas. Instead the Land of Canaan was sprinkled with many small city–states. And each had a King. King in quotation marks – because a typical kingdom may have a jurisdiction of maybe 10 kilometers radius.

And we find no significant records of writing until maybe the 15th century B.C.

By the way – this land is usually called the Land of Canaan in the Hebrew bible. The term Land of Israel was seldom used until much later. The Israelites viewed themselves eventually as the people of Israel but viewed the land where they lived as the Land of Canaan.

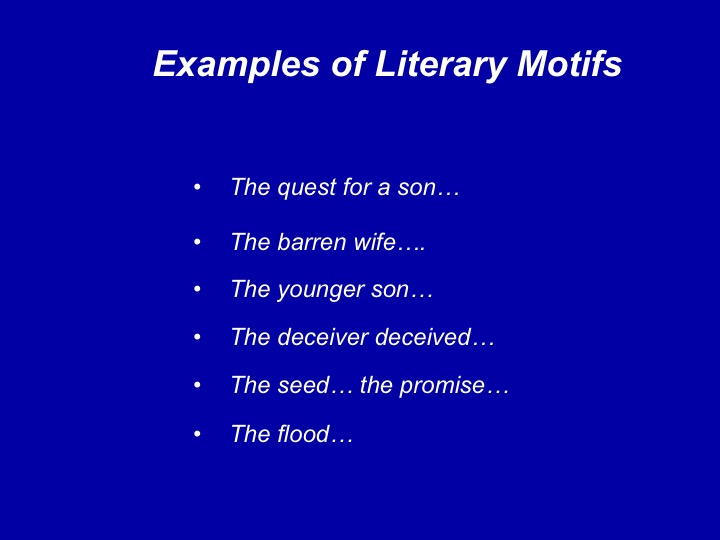

I want to briefly mention an important literary idea – the notion of motifs.

We see motifs in all literature – right up until today. Skillful writers use motifs to impart meaning into narratives. And when a writer repeats a motif it can be a very effective way to teach.

An

important idea is that motifs are often shared across multiple cultures –

especially if they interact.

And this is the nature of ancient literature. Meaning is conveyed not through historical or scientific facts – everything is conveyed through narrative – shared stories.

Let’s talk about some motifs in Genesis.

The Abraham cycle, which we will read in a few weeks, contains a poignant motif of the quest for a son. We will talk about that when we read it. But as you will see in a moment other near eastern literatures use that motif also.

Strikingly in Genesis we see a recurring pattern of barren wives. Abraham and Sarah, Jacob and Rebecca, Jacob and Leah, Hannah, mother of Samuel, the mother of Samson. There must be a message there and we will explore it when we get to that later.

The younger son. In patriarchal societies like the near east family life is dominated by primogeniture – the understanding that the oldest son inherits his father’s estate over all the other sons. Time and again in Genesis and later in the Bible the younger son is the winner. Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, David, Solomon. There is a message there and we will explore it – but not today.

The deceiver deceived. This is almost a form of karma from Asian religions – but we see it in the life of Jacob – who deceives his older brother Esau from his birthright by fooling their blind father Isaac into blessing the younger Jacob. Then later in life Jacob’s is deceived by his Uncle Laban into marrying Laban’s older daughter Leah instead of the more beautiful daughter Rachel. When Jacob protested Laban explained that in this land (Mesopotamia) the oldest comes first. Then later Jacob the deceiver is deceived again by his sons into thinking his son Joseph had died, when in fact they had sold him into slavery in Egypt. The deceiver was deceived twice.

A recurring motif in Genesis and later books is the ongoing promise of the seed, which includes the promise of a great nation. This motif appears to be unique to the bible.

And the flood – occurs in several near eastern stories. We will review that when we read the flood story.

These motifs work because

they create conflict – and conflict creates drama – and drama drives

literature, which can then communicate truths. And great literature is about

communicating important truth. I will say it again – neither Genesis nor any of

the other ancient near east literature we will review in a moment make any

attempt to record historical or scientific facts. That is not their purpose. The vehicle for

communication in the ancient world is narrative – stories that convey meaning.

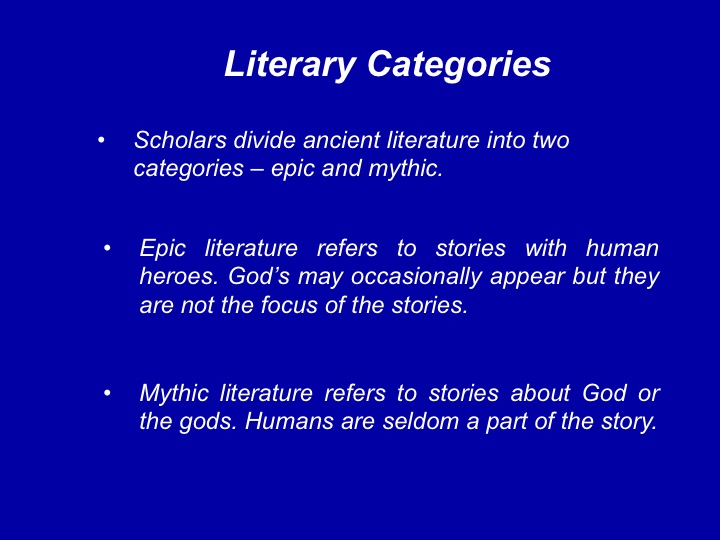

So before we briefly review some of the literature of the ancient near east let’s first define some literary categories.

It is important to understand what these mean – because outside of the world of scholars modernistic thinking misunderstands these terms.

Scholars define epic literature as stories with human heroes. Mythic literature as stories about God or gods.

By this type of lumping

Genesis 1-11 is considered more mythic in character because God plays a major

role. The remainder of Genesis 12-50 is

more epic in character. God occasionally

intervenes but the stories are very human. They are all about the family of

Abraham and their evolution.

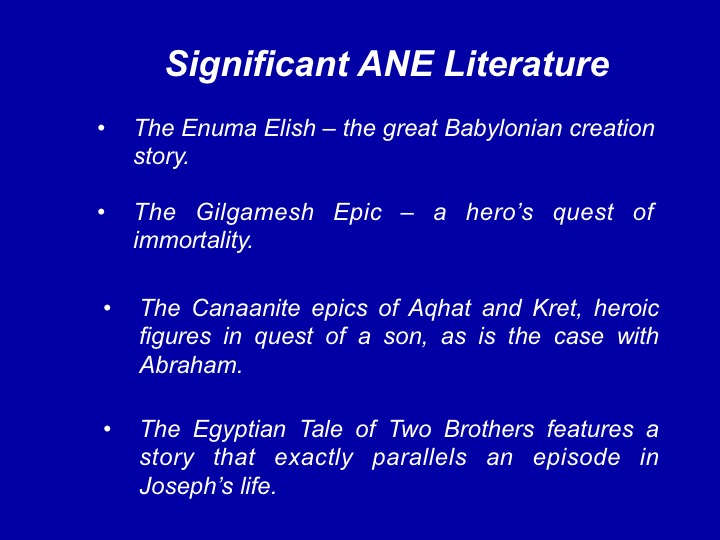

So let’s talk about the major, known ancient near east literature works. And I have to emphasize known because almost assuredly we have only recovered a small fraction of the literature of that time and place.

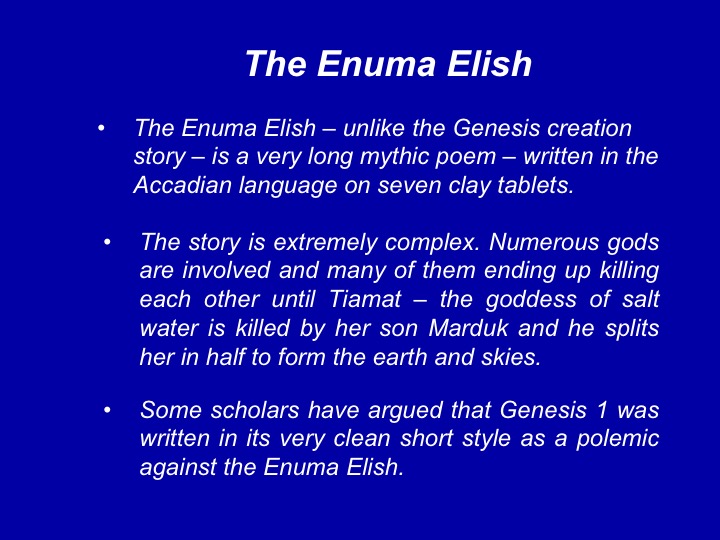

First is the Enuma Elish – the great Babylonian creation story of the creation of the universe. We will talk about it in a minute in order to understand what it was and how it was significantly different than for example the first chapter of Genesis. But is important to understand because it pre-dated the writing of Genesis and almost certainly the writer of Genesis knew it thoroughly since the patriarchs were from Babylon.

The Gilgamesh Epic – not a religious work but in the classic definition of an epic it is about a human hero – an ancient King named Gilgamesh and his quest. Because it includes the Babylon flood story we will review it when we read the flood story in Genesis 6-8.

In the land of Canaan we find the Canaanite epics of Aqhat and of Kret – again heroic figures both on a quest for a son, and that is a motif of the Abraham story we will read.

Finally – one last example, but their could be more – from Egypt we have the Tale of Two Brothers – another epic. But containing a story with an exact parallel to a story in Joseph’s life.

The creation begins with the universe pre-existing in a formless state, from which emerge two primary gods – male and female.

The poem has about 1000 lines – written in the Accadian language on seven clay tablets. It was recited to the people of Babylon annually at their New Year festival.

Not exactly like Genesis 1.

Everything about Genesis 1 is clearly stating that God is one and God is not like this and God alone created everything. Not only did it clearly state their was only one God but used demythologizing language to completely ignore any other gods such as the sun god or moon god.

The epic was scribed onto 12 clay tablets. It may be the oldest surviving copy of ancient literature – believed to date from the 18th century B.C.

Utnaptishtim tells him that he is immortal only because he survived the great flood and one of the gods gave him eternal life because of his bravery in the flood.

Because

it includes the Babylon flood story we will review it when we read the flood

story in Genesis 6-8.

In addition, although literary texts are the most exciting discoveries in archaeological excavations, note that the most common written records found, by far, are economic and legal texts. These detail the everyday life of the ancient Near East. And these play a role in our study of the Bible, the best example of which are the Nuzi documents from northern Mesopotamia, which we will survey when we study Abraham.

A simple example. When Abraham’s wife dies in Genesis Abraham buys a plot of land to bury her. The scripture describes for us that Abraham bought the land and the trees. He paid 400 shekels. Is that a lot, is that a little? Our experts who have translated all of the finds in Nuzi tell us that it is in fact the standard price for a plot of land. But we wonder why it said that he bought the land and the trees. Don’t you always buy the land and the trees? Again, the many legal documents we find in Nuzi inform us that in Mesopotamia you always bought either the land or the trees or both. Some people sold land and kept the right to harvest the fruit of the trees. But Abraham bought it all - the land and the trees.

We will learn more about some of the customs of the people when we read the Abraham story.

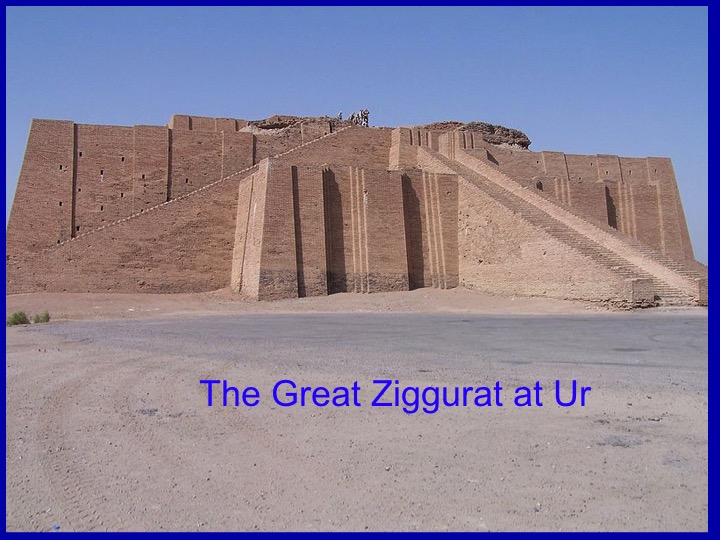

Another parallel is architectural.

The tower of Babel story in Genesis is an example. Babel is the Hebrew word for the city of Babylon. So it refers to a tower built in Babylon to stretch up to heaven.

Most

scholars are convinced this reflect the Ziggurat tradition in Mesopotamia. Babylon, Nineveh in Assyria, and Ur all had

great ziggurats – mostly in bad shape today except for this beautiful one

uncovered in the ancient of Ur in the 20th century. In the Mesopotamian tradition these ziggurats

were supposed to reach heaven.

These numerous parallels

lead us to the conclusion that Israel did not exist in a vacuum but, instead,

participated to a large extent in the greater cultural world of the ancient

Near East.