History of Christianity Class 4

Persecution and Extreme Christianity

History of Christianity Class 4

We are now on Lesson 4.

To this point in our study, the lessons have described the contexts of Christianity within Mediterranean culture, Greek civilization, and Roman rule; its birth within the symbolic world of Torah; its first rapid expansion; and the composition of its earliest literature. But it is premature to speak of “Christianity” in these earlier stages as though it were a fully defined and distinct entity; the process of its formation continued into the 2nd century and only then achieved greater clarity. We will trace the history of this continuing formation in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, beginning in this lesson with a discussion of many of the dangers that Christianity was facing, including Christian persecution, & extreme Christianity.

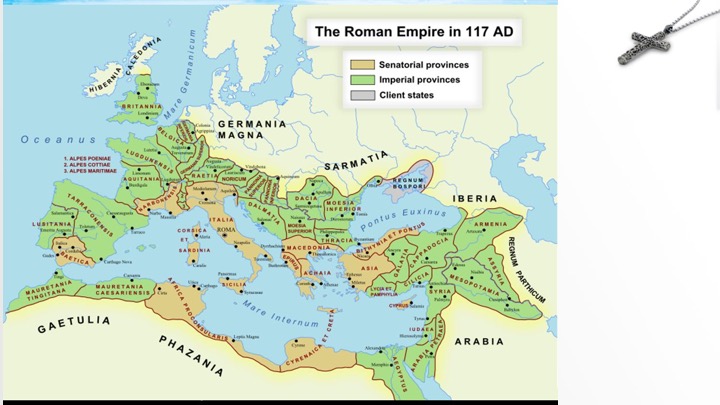

To provide some context and background for this discussion let's look at a map.

History of Christianity

This is the Roman Empire early in

the 2nd Century

A few important points. The Roman Senate, in dealing with how to manage a very large empire, decided that the only practical way to do it was to divide it into Senatorial provinces, shown in brown, which were relatively safe, and Imperial provinces, shown in green, which were predominately on the fringes of the empire, and by this time were under constant threat from outside interests.

The Senate wisely gave the Roman military authority to deal with internal insurgencies, as well as outside invasions, which were already being threatened from the Parthian Kingdom on the east, the Germanic tribes from the north, and “barbarians” from the north end of Britannia.

Another point – some of the new house churches were in the safe part of the empire but many were in the dangerous part, so the early Christians had to deal with that.

So what were the biggest issues early Christianity had to deal with?

The 3 Major “Issues” for Christianity in the 2nd Century

1. How do we fit into the dominant culture of this time (the Greco-Roman culture). Can we get along but still remain holy or separate?

2. How do we deal with Judaism? – we were initially a sect of Judaism, but now clearly are rapidly becoming Gentile.

3. And most importantly, how do we deal with our own diversity? The rapid growth of Christianity across a large geographical area with varying cultures had begun to exhibit variants of Christianity that were very different than what came to us from the original apostles.

Two examples preceding Christianity show such premises at work and help explain the subsequent experience of Christ-believers when they became sufficiently numerous to be noticed by outsiders. Although Judaism was granted imperial recognition as a national religion—and reciprocated by offering sacrifices and prayers for the emperor—there are instances of its being persecuted.

For example, the Maccabean books show that resistance to syncretism under Antiochus IV Epiphanes in Palestine led to executions, most famously that of the aged Eleazar and of the seven Maccabean brothers with their mother. Philo tells us of anti-Semitism in Alexandria that expressed itself in local riots against the Jews, requiring an appeal to the emperor for assistance.

Even among non-Jews, philosophers who challenged traditional beliefs or who withdrew from religious practices, such as the Epicureans, were suspected of subversion. Individual philosophers who challenged social mores or popular religious tenets were sometimes put to death (Socrates and Zeno) or exiled (Dio of Prusa, Epictetus, Seneca) as “enemies of the Roman order.”

History of Christianity

Societal Reasons for Persecution

The Roman Empire, like the Greek Empire before it, was concerned above all with the good order on which the stability and prosperity of the city-state and the empire depended.

The worship of the gods was an inherent and necessary part of such world maintenance; the participation of all in the “city of gods and men” was a fundamental premise of ancient politics. Plutarch despised the Epicurean philosophy primarily because its denial of the gods was attached to a withdrawal from political involvement. It thus represented a challenge to good order and a threat to society.

Although the Roman Empire was generally receptive to new religions, especially when, like Judaism, they were ancient traditions of a conquered nation, participation in the empire’s benefits required the recognition of the empire’s gods. Cults regarded as subversive were dangerous.

Even when a cult enjoyed imperial recognition or official favor, it could be the target of local resentment and harassment. Ancient people were no less prone than we are to fear and resent that which is strange.

Two examples preceding Christianity show such premises at work and help explain the subsequent experience of Christ-believers when they became sufficiently numerous to be noticed by outsiders. Although Judaism was granted imperial recognition as a national religion—and reciprocated by offering sacrifices and prayers for the emperor—there are instances of its being persecuted.

For example, the Maccabean books show that resistance to syncretism under Antiochus IV Epiphanes in Palestine led to executions, most famously that of the aged Eleazar and of the seven Maccabean brothers with their mother. Philo tells us of anti-Semitism in Alexandria that expressed itself in local riots against the Jews, requiring an appeal to the emperor for assistance.

Even among non-Jews, philosophers who challenged traditional beliefs or who withdrew from religious practices, such as the Epicureans, were suspected of subversion. Individual philosophers who challenged social mores or popular religious tenets were sometimes put to death (Socrates and Zeno) or exiled (Dio of Prusa, Epictetus, Seneca) as “enemies of the Roman order.”

History of Christianity

Sources of Persecution

In its first centuries of its existence, Christianity was particularly vulnerable to attack from both Jews and Gentiles. It was sociologically underdetermined and ideologically oppositional.

As an intentional community, the Christian cult drew from both Jews and Greeks but had no secure place in the world. It did not meet in established temples or synagogues but in households.

Its understanding of “holiness” demanded an opposition against paganism (with its idolatry) and Judaism (with its Law).

The earliest evidence of opposition comes not from the side of the Roman Empire but from the side of the Jews.

The question of the involvement of Jewish leaders in the death of Jesus is difficult and contentious. Certainly, he was executed under Roman order, but it is likely that some degree of cooperation if not instigation can legitimately be ascribed to some Jewish leaders. With the exception of the Gospel of Luke, however, the Gospels certainly tend to exaggerate the complicity of the Jewish population in the death of Jesus.

Nevertheless, the evidence of the New Testament (especially Acts and Paul’s letters) supports the fact that in the first decades, Jews harassed and sought to subvert the Christian movement. In fact, Paul attests that he was a persecutor of the church before his conversion and that after becoming an apostle was persecuted by his fellow Jews.

For the Jews, the problematic claim was not that “Jesus is Messiah,” for such a confession (right or wrong) was compatible with Jewish identity. The troubling claim was that “Jesus is Lord,” that is, as the son of God, he shared fully in the life and power of the divine. This claim offended Torah observers who interpreted the manner of Jesus’s death as an indication that he was cursed by God and who believed that declaring Jesus as Lord was the equivalent to polytheism.

The sources speak of two forms of harassment: stoning (attested by Paul and Acts) and excommunication from the synagogue (attested by Acts and the Fourth Gospel).

Christians put Roman rulers and administrators in a difficult situation.

So long as Christianity flew under the flag of Judaism (as a “sect” of Judaism), it would enjoy the same privileges accorded that ancestral tradition, but when relations with Jews were severed, as they were by the late 1st century, the subversive elements in Christianity could not be ignored.

History of Christianity

Sources of Persecution from Empire

Insofar as it succeeded in expressing egalitarian ideals, it was inherently threatening to the stratified world of ancient patronage, and therefore threatening to the Empire.

Over time, Christians became more aggressive in their attacks on Gentile idolatry: The gods of the nations were idols and demons. There was also intense proselytism.

The earliest non-Christian sources concerning Christians (Suetonius, Tactitus, and Pliny the Younger) described them as highly superstitious and extremely stubborn.

The separateness of the cult, above all its refusal to participate in the “city of gods and men,” marked its members for the same attacks that had been made on Jews: They were atheists and were guilty of misanthropy.

History of Christianity

Imperial Persecution – What Do We Actually Know?

Constructing an adequate historical account of persecution from the 1st to the 4th centuries is difficult. The precise events are uncertain, and there are large gaps in the evidence.

For the most part, evidence comes from Christian sources, which understandably tend to maximize state opposition and oppression. Thus, in Christian lore, Marcus Aurelius is a notorious persecutor, but there is little evidence of this persecuting activity under him.

It is difficult to distinguish the occurrence of local riots (as in the Martyrdom of Polycarp) or even regional repression (as in Pliny the Younger) from systematic state persecution, or temporary spasms of persecution from sustained efforts.

The numbers of Christians killed over these centuries is particularly difficult to assess, although to be sure, the effect of persecution should not be measured only by numbers of fatalities.

It seems clear, moreover, that Christians enjoyed periods of peace that sometimes lasted for decades.

Overall, however, a consistent pattern appears to emerge: When Christians were persecuted by state authority, it was as a corollary of some larger political concern for the security of the imperial order.

History of Christianity

Persecution – What Do We Actually Know? (2)

The best known (or suspected) persecutions can be summarized according to century.

In the 1st century, Nero killed Christians in 64 as a way of deflecting blame for the fire in Rome from himself. According to Tacitus, Nero “inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations... [and] hatred of mankind.” A persecution under Domitian (89–96) is postulated as the backdrop to the oppression and murder depicted in the book of Revelation.

In the 1st-century persecution under the emperor Nero, it was said that Christians were mocked, attacked by dogs, crucified, and burned.

In the 2nd century, a regional repression under Trajan (109–111) in Asia Minor is known from the letter of Pliny, as well as from the letters of Ignatius of Antioch. Under Marcus Aurelius (162–177), a persecution in Lyons can be documented and may have been more widespread.

The 3rd century saw more violent outbursts of persecution under Septimius Severus (202–210), Maximinus (235), Decius (250–251), and Valerian (253–258). These were especially virulent in North Africa. In contrast to such spasms were lengthy periods of peace.

The most systematic and sustained persecution was the last, under Diocletian and Galerius (302–311), which led right up to the issuing of the Edict of Milan in 312, finally granting religious toleration to Christians.

History of Christianity

Effects of Persecution

Although the exact facts about the centuries of persecution are difficult to ascertain, the effect on Christianity is clear.

Under conditions of uncertainty and duress, Christianity continued to grow, partly by means of conversion and partly by means of childbirth—the refusal to practice abortion or infant exposure led to larger families.

Persecution generated two responses from within Christianity: the celebration of martyrdom as perfect discipleship and the writing of apologetic literature in defense of the movement.

The long-term effect on the Christian psyche was real: Like an abused child for whom early trauma continues to define later behavior, Christians tended through the ages to bear a sense of aggrievement and to become abusive toward others in turn when they came into power. We will see how imperial Christianity turned the state instruments of persecution on Jews, pagans, and those considered to be heretical in their Christian teaching.

Extreme Christianity (2nd and 3rd Century)

But there were other manifestations of the Christian religion in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, even those that can be considered extreme. The deeply experiential character of this religion manifested itself especially in phenomena that, at the same time, resembled aspects of Greco-Roman religion and appeared to threaten good order within Christianity. None of these manifestations truly represented Christianity’s future, but none of them was ever totally suppressed, and each recurred in different forms through the centuries.

One manifestation of Christianity is this period was a distinctive religious sensibility that extended and amplified an element found in the New Testament Gospels and Acts: an emphasis on wonder-working and the working of divine power in visible ways. This was expressed in a variety of new gospel narratives and acts of apostles.

The infancy gospels of James and Thomas focus exclusively on the birth and childhood of Jesus. They place an emphasis on wonder-working and the physical purity of the body.

The infancy gospel of James depicts the birth of Jesus as miraculous, almost as if the less human Jesus is, the more divine we can assume him to be.

In the infancy gospel of James, the perpetual virginity of Mary is ensured by the miraculous conception and birth of Jesus. When Jesus is born, time stops and all creation grows silent; he appears first as a shining light and only slowly takes the form of an infant.

In the infancy gospel of Thomas, the child Jesus is the source of both cure and blessing to his family and neighbors, so overwhelming are his acts; Jesus is portrayed as captive to his own extraordinary powers, only slowly learning how to turn them to good.

The Acts of Paul, Andrew, John, Peter, and Thomas (all composed in the 2nd and 3rd centuries) continue the literary tradition of the canonical Acts of the Apostles but focus almost exclusively on the apostles as wonder-workers who triumph over all, even in their death as martyrs.

History of Christianity

Extreme Christianity (2nd and 3rd Century) (2)

Although naive in some ways—they are filled with animal tales, nature wonders, and strange deeds—these narratives convey a sense of Christianity as a movement that exercises supernatural power and poses a radical threat to conventional mores.

The order of the household is threatened by a version of the “good news” that demands of its hearers—especially women— virginity and singleness. The apostles are itinerant wonder- workers who find their way into households and “seduce” wives by their preaching, convincing them to commit to a celibate life; the elevation of virgins and widows means women are not defined by biological or domestic roles.

Women in these accounts are definitely not “submissive to their husbands” but either leave them or assume leadership roles in the assembly; most impressively, Paul’s follower Thecla cuts her long hair, dresses as a man, baptizes herself, and undertakes a career in preaching.

The order of the empire is equally threatened by an aggressive assertion of God’s sovereignty. These stories show emperors and kings alike unable, despite violent efforts, to stop a movement that subverts their authority. Even when they put an apostle to death, power continues to emanate from the body.

That is a brief review of some of the many late gospels and books of Acts. Let us turn now to what we are calling Extreme Christianity. We will take a brief look at three examples:

History of Christianity

Extreme Christianity - the Montanist Movement

A second manifestation of radical Christianity was a movement that emphasized personal experience of the Holy Spirit. This was the “New Prophecy” or Montanist movement, named for its founder, Montanus.

Beginning either in 156/7 or 172, the movement claimed the outpouring of the Holy Spirit (the “Paraclete” of John’s Gospel) on Montanus and two female companions, Prisca and Maximilla in Phrygia. Members of the movement were “pneumatics” (spiritual people) and outsiders were “psychics” (merely natural people).

Forms of ecstatic behavior were attested in Phrygia before the time of Christianity. For example, The Golden Ass, written by Apuleius, describes the eunuch priests of the mother goddess Cybele in the ecstatic throes of self-mutilation and ecstasy. As Paul’s Letter to the Galatians suggests, Phrygia was a territory given to radical behavior: His converts in that area also sought to cut off their foreskins as a sign of religious enthusiasm.

o The impulse toward ecstatic utterance also extended a theme of earliest Christianity: In addition to Jesus’s promise of the Holy Spirit in John’s Gospel (ch. 16), see the portrayal of the church prophesying and speaking in tongues in Acts 2, as well as Paul’s discussion of tongues and prophecy in 1 Corinthians 12–14.

o As in the apocryphal Acts of the Apostles, the prophetic power of celibate women provides a radical alternative to the domestic roles society imposed on them; thus, the New Prophecy implicitly challenged conventional society.

• The Montanist movement was strongly ascetical; it forbade second marriages, imposed strict rules for fasting, and advocated the willing acceptance of martyrdom rather than flight in times of persecution.

o It was sufficiently popular to have converted the intellectual Tertullian in North Africa in the year 206; his last writings are marked by Montanist tendencies.

o The prediction that the “New Jerusalem” would appear in the village of Pepuza probably hastened, by its nonrealization, the fading of the movement.

o It was condemned by Asian synods before the year 200 and by the bishop.

History of Christianity

Extreme Christianity - Marcionism

Another teacher, Marcion, came to Rome in 140 from Pontus in Asia Minor. He proclaimed a Christianity that was based on an absolute division between matter and spirit: Physical reality is evil, and only spirit is good.

Marcion taught that the creator God of the Old Testament is a god of wrath, who by his creation, entrapped humans in material reality; Jesus represents an alien god of the spirit who liberates humans from the body.

Among the New Testament writings, Marcion considered only 10 letters of Paul to contain the true gospel; other writings were contaminated by the “Jewishness” sponsored by the creator God who had revealed the Law. Further, for Marcion, only an edited version of “Paul’s Gospel” (the Gospel of Luke) portrays Jesus truly. Marcionism was profoundly and essentially anti- Semitic in character.

Marcion founded a number of churches that were remarkably successful, especially in the East. His communities were strongly ascetical in their behavior: Virginity and fasting were essential to the freedom of the spirit.

History of Christianity

Extreme Christianity - The Gnostics

The discovery of a collection of Coptic compositions at Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt in 1945 confirmed the reports of ancient ecclesiastical writers concerning such teachers as Valentinus (in Rome, c. 135) and Basilides (in Egypt, c. 135), who sponsored a strongly dualistic and individualistic version of Christianity that has come to be called Gnosticism. This term covers a spectrum of variations, but certain characteristics are held in common.

o The soul is a fragment of the divine that has tragically been separated from its source and trapped in the darkness of the body, where it forgets its origins and destiny and falls into ignorance.

o Jesus is the revealer who comes from the light and announces to the soul its origin and identity. “Saving knowledge” (gnosis) is a form of self-realization: where one is from, who one truly is, and where one is destined to return.

o The way back to the light is through a liberation from the body and its physical entanglements, especially through sexual abstinence and fasting; marriage and children simply perpetuate the tragedy of somatic existence.

Extreme Christianity - The Gnostics (2)

The Gnostics divided humans into three categories: the hylic (lost in materiality), the pneumatic (self-aware), and the psychic (who can choose either way).

o The “spiritual people” saw themselves as superior to the members of the “catholic” community, who were hylic because of their enmeshment in matter. Gnosticism privileged the destiny of the individual over the survival of the community.

o The literature also reveals hostility toward the institutions of the “great church” and the “apostolic men” who cultivate a community that is lost in ignorance and materiality.

o Those drawn to Gnosticism tended to find their way into Manichaeism—founded by the Persian Mani (216–276)— which had both Christian and non-Christian forms, but versions of Gnosticism also endured into the medieval period, as among the 13th-century Albigensians.

Extreme Christianity – Understanding Its Importance

It is difficult to determine how many were attracted to these rigorous forms of Christianity. In some parts of the empire Marcionites seemed to be in the majority. We do know that they were numerous enough to generate a vigorous response from the more orthodox Christians.

But these radical phenomenon are of great importance for assessing the character of Christianity as it grew within the Roman Empire.

They continued the original diversity of Christianity in even more dramatic ways; Christianity was certainly not yet just “one thing.”

They continued to insist on a key element in earliest Christianity, namely, religious experience of various kinds. They continued to challenge the unity of the church, which would eventually expel some manifestations (such as Gnosticism) and domesticate others (such as miracle-working and martyrdom).

And so Christianity was faced with a significant issue with it's own diversity. And how they decided to deal with that will be reviewed next week as we wrap up the 2nd and 3rd centuries.

< Audio >

Next Week - The Shaping of Orthodoxy

History of Christianity Class 4 Slides