History of Christianity - Lesson 7

The Spread of a Christian Culture

Mike Ervin

History of Christianity - Lesson 7

The Spread of a Christian Culture

As we have seen, the effects of being established as the official religion of the Roman Empire went far beyond safety, legitimacy, or even privilege. The emperor and the state bureaucracy were intimately involved with the internal affairs of the church. Christianity had become a public political religion in precisely the fashion of the Greco- Roman polytheism that preceded it. In this class, we will discuss the role of conversion as an instrument of statecraft and the geographical extension of Christianity. We will also see how the now-official religion extended itself both spatially and temporally in order to meet its new cultural obligations.

Internal Stresses

The challenge of being a state religion put severe internal stress on Christianity. Despite the impressive institutional and intellectual developments it had accomplished in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, it remained ill-prepared for the task of providing the glue for a society.

Starting as a sect with a distinct countercultural disposition, it was eschatologically oriented: This world is not permanent or even necessarily valuable. There is much in this religion that argues against stability and good order: Celibacy is better than marriage, poverty than wealth, humility than arrogance, obedience to God over obedience to humans.

The canonical writings of Christianity are far from providing a consistent code of behavior even for religious matters, much less directions for a civilization to organize itself.

In the 2nd and 3rd centuries, radical impulses continued to flourish under the name of Christianity, despite the efforts to shape a centrist orthodoxy.

Especially in the East, where imperial rule remained more stable, the precedents of pagan culture provided much of the form for the Christian empire.

The basic forms of Greek paideia—though suffused with biblical content—remained consistent: logic, philosophy, rhetoric, and the plastic arts.

As the imperial religion, Christianity was a Greco-Roman religion, with only vestigial connections to Judaism. Even Scripture was in Greek and interpreted through Greek rhetoric.

The increased instability of the empire in the West, in turn, would force Christianity both to engage new cultural realities and to forge a distinctively Christian culture as an instrument of civilization among barbarians. This would evoke flexibility and creativity rather than stagnation.

The Extension of Christian Culture

As we have seen, the effects of being established as the official religion of the Roman Empire went far beyond safety, legitimacy, or even privilege. The emperor and the state bureaucracy were intimately involved with the internal affairs of the church. Christianity had become a public political religion in precisely the fashion of the Greco- Roman polytheism that preceded it. In this lecture, we will discuss the role of conversion as an instrument of statecraft and the geographical extension of Christianity. We will also see how the now-official religion extended itself both spatially and temporally in order to meet its new cultural obligations.

Geographical Expansion

• Under imperial authority, missionary work took on a new character: It became more intentional and more centrally organized.

• During the era of persecution, converts to Christianity were made primarily through networks of association and personal influence, rather than through sudden mass conversions stimulated by preaching or wonder-working. Evangelization was mostly carried out on a small scale; growth in numbers was, in no small measure, due to strong birth and survival rates among Christians.

• After official establishment of the religion, missionaries were often commissioned by imperial authority to work with both the leadership and the populace of other nations and tribes. The king of a client state would “convert” the people by himself converting and then declaring Christianity to be the new official religion of the realm.

Between the 3rd and 5th centuries, substantial territories and populations become “Christian” through such processes.

Christians appeared in Persia in the 3rd century and were persecuted under the Sassanid Empire until the 450s.

The kingdom of Armenia, a Roman client state adjacent to Asia Minor, made Christianity the official religion under King Tiridates III in 301 as a result of the influence of Gregory the Illuminator; Armenia was, in fact, the first kingdom in history to declare itself officially Christian.

The kingdom of Georgia, formerly a Roman province, made Christianity the official religion under Mirian III sometime between 317 and 327 (the dates are disputed).

In Yemen, at the tip of the Arabian Peninsula, a teacher named Hayyan established a Christian school around 400; Christians survived there until overrun by the Muslims in the 7th century.

Ethiopia became officially Christian in 330 under the ruler Ezana of Axum.

The East German tribe known as the Vandals had some members converted to Christianity in 364 under the emperor Valens. In the 4th and 5th centuries, both the Visigoths and the Ostrogoths converted to Christianity.

Several aspects of this geographical and demographical extension are worth noting.

The translation of the Bible into new languages (Ethiopic, Georgian, Armenian, Gothic) was a key element in the “Christianizing” of new lands and people. Christianity in its new languages continued to be a literate and scriptural religion.

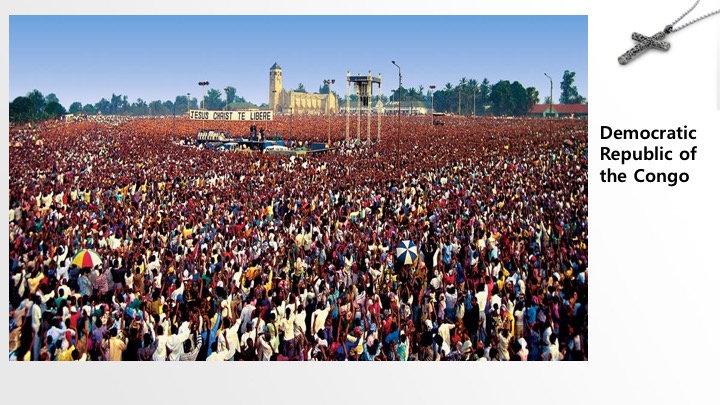

Christianity became even more catholic (in the sense of “universal”) as it embraced new populations and cultures beyond its original Jewish, Greek, and Roman roots.

The character of the “Christianity” that thus expanded also had some ambiguous aspects.

It was often superficial, with strong elements of indigenous paganism remaining; even more than within the empire, small villages and remote rural areas maintained traditional ways for centuries after officially being declared Christian.

It was often practiced in versions that were at odds with orthodoxy as it developed. Thus, Persian Christians adopted a teaching on Christ that was termed Nestorian, while new Christians in Ethiopia and Armenia were monophysite in their tendency; the Germanic converts in Europe were predominantly Arian in their convictions.

The fringes of the empire thus became a refuge for “heretical” versions of Christianity; the further from imperial control, the greater the diversity of Christianity.

The Organization of Space

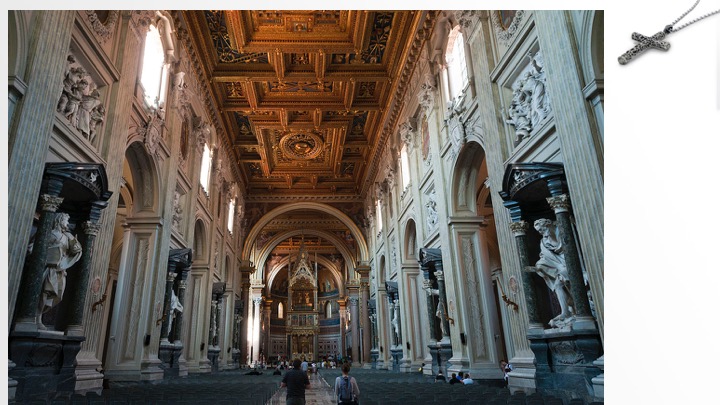

Another expression of Christian expansion as the imperial religion was the organization of space in Christian terms.

The contrast to the pre-Constantinian era is particularly sharp in this regard given that Christianity formerly needed to be hidden because of the threat of persecution.

In the 2nd and 3rd centuries, Christians met for worship in private homes, in buildings constructed for worship that were like houses (Dura-Europos), or in the burial chambers called catacombs.

Worship, in turn, was fitted to these small spaces, yet as we have seen, there had already occurred (in the compositions called the Church Orders) an expansion of organization and rationalization of worship.

With the expropriation and construction of great basilicas as places of Christian worship, liturgy expanded to fill the space allotted to it.

The very term “liturgy” derives from the “public works,” such as sacrifices, festivals, and processions, that were sponsored by wealthy patrons in Greco-Roman civic religion.

Christian liturgy in large spaces began to take on the characteristics of such public liturgy. We find open-air processions, elaborate rituals (bowing, genuflecting, arm gestures), rich garments, and the use of musical chants.

The anaphora, or formal Eucharistic prayer, became a lengthy and public profession.

Just as “sacrifice” was at the heart of Greco-Roman religion, a holy act carried out by official priests on behalf of the populace and the city-state, so did the Christian Eucharist lose the sense of an intimate meal and develop more fully the sense of a sacrifice offered for the populace by a class of priests.

The Greco-Roman love of art and adornment found new expression through the portrayal of specifically Christian themes rather than, as before, the themes of gods and goddesses in Greco-Roman mythology.

Statuary was dedicated not to the portrayal of the gods but to the portrayal of biblical figures and, eventually, to those whose holiness placed them at a level above the merely human, the saints.

Painting (in the form of frescoes), mosaics, and funerary art (on sarcophagi) displayed biblical themes, including stories from the New Testament.

Movement from place to place in public became a prominent feature of imperial Christianity.

In the city of Rome, “station churches” represented stopping points for liturgical processions, with the chanting of hymns during the procession and prayers carried out in each station church.

Pilgrimages were made to the tombs of the martyrs, where the sharing of a sacred meal (the refrigerium) was a popular form of veneration of the saints; the pagan antecedents of this practice are clear, and the practice worried such teachers as Saint Augustine.

Just as pilgrimages were made in Greco-Roman religion to prophetic and healing shrines—people of all social classes went to hear the oracles given by Apollo at Delphi, and thousands traveled to seek healing at the shrines dedicated to Asclepius—so did Christians make pilgrimage to the holy men and women in the desert to experience direct contact with power.

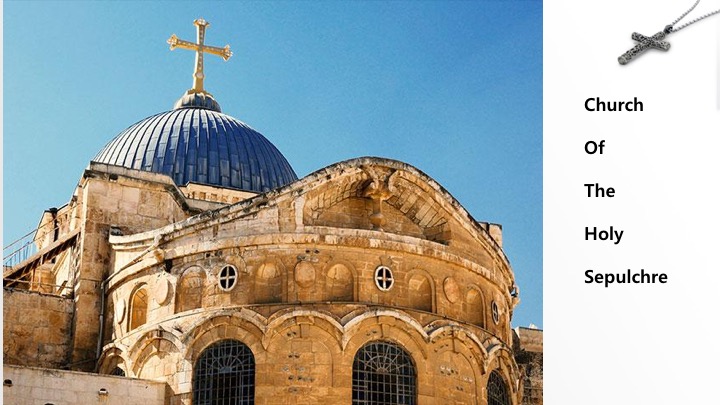

More elaborate pilgrimages were also made to the Holy Land, the location of the biblical story and, therefore, considered to be particularly filled with power. For example, Helen, the mother of Constantine, traveled to Jerusalem and discovered the relic of the Holy Cross. Constantine built the Church of the Holy Sepulchre on the supposed site of Jesus’s burial.

Constantine built the Church of the Holy Sepulchre on the supposed site of Jesus’s burial in Jerusalem; to this day, it is a place to which Christians continue to make pilgrimages.

The Sanctification of Time

Christianity also extended its cultural influence through the sanctification of time. The life of individual Christians was marked at each stage by rituals that came to be called sacraments.

The most ancient of these rituals are connected to entry into the community: baptism, confirmation, and the Eucharist. When children are baptized at birth, these rituals are separated in time and become marks of growth (confirmation = “maturity”).

The sacrament of repentance (or “penance”) sanctified the turn from sin during the course of adult life.

Ordination to the priesthood was preceded by a number of “lesser” orders (porter, lector, acolyte, exorcist) and two “major orders” (subdeacon and deacon), representing multiple levels of initiation.

The last sacraments reaching official status were matrimony and final anointing (for the terminally ill).

Time itself was sanctified by an ever-more elaborate liturgical year that served to bring the biblical past into the present by celebrating moments in the history of salvation and the life of Christ.

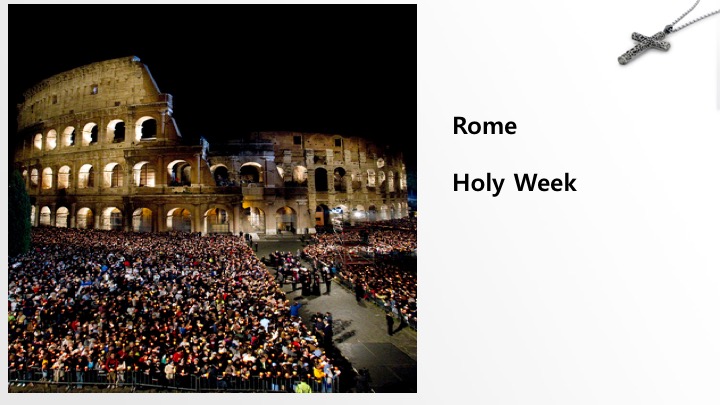

Sunday, the traditional Christian celebration of the Resurrection of Jesus, was declared a public holiday by Constantine.

Over time, a seasonal liturgical cycle contemporized the events of the sacred past. The oldest cycle revolved around Easter, the celebration of the Resurrection: It was preceded by the 40-day period of Lent, followed by an “Easter season,” and concluding with the feast of Pentecost.

A similar cycle centered on Christmas, the celebration of the birth of Christ. It was preceded by the season called Advent (“arrival”) and followed by a “Christmas season,” concluding with the feast of Epiphany.

The time outside these cycles was designated as “ordinary time.” In the liturgy, the Gospel stories concerning Jesus’s words and deeds were read.

Another liturgical cycle began to develop, centered on the celebration of the saints: first the martyrs, then the “confessors” (those who did not capitulate to persecution though they were not killed), and then virgins and widows. The sanctoral cycle celebrated the “communion of saints,” linking the church militant on earth—militant because it still needed to do battle with sin and the forces of darkness—with the church triumphant in heaven.

Like pagan Rome, then, both the old and new Christian Romes saw time punctuated by the rhythm of fasti and nefasti, holy days and ordinary time, sacred festivals and profane activities. And as Christianity’s presence pervaded everything, it was inevitable that Judaism, even when minimally protected by law, would become more vulnerable, both psychologically and in reality.

Christian Culture in the Context of Empire

After Constantine, we see a distinctively Christian culture progressively being shaped within the context of the empire.

Especially in the East, the forms of Greek culture based in the Greek language continued—rhetoric, philosophy, art and architecture, and music, but they were now suffused with Christian content, above all, biblical themes. In the West, the Latin language would dominate the communication of the good news to ever more barbarian peoples.

In the East, continuity was most evident and changes were subtle, while in the West, challenges to traditional culture were more marked, and lines of continuity with classical culture were fragile and would eventually be broken.

Religions and Cultures

In our first class of this series I presented you with the quote from Andy Dearman about the religion of Israel saying in effect, the religion of ancient Israel did not develop in a vacuum; it was influenced by the the Near Eastern Culture around it and it in turn influenced that culture. I believe you can see in covering today's material that we can see that again playing out

In joining the culture of the Empire forced some major changes in the liturgy, behavior, and yes the culture of the Catholic church. And just as evident, adopting Christianity as the religion of the Empire changed the culture of the Roman Empire drastically; in about a century or two it changed from a predominately Greco-Roman and pagan culture to a predominately Christian culture.

Next Week

This now sets the stage for next week, when we ask the question of what else significantly changed as a result of Christianity becoming the officially approved state religion. And that will lead us to a new Radical version of Christianity that never existed before, namely Christian Monasticism.

Monasticism developed rapidly in the 4th century and continued for centuries thereafter to influence Christianity. All of this happened in the deserts of Egypt and later Palestine. We will be examining the Desert Fathers and Mothers.

See you next week.

< Audio >

Lesson 7 slides