History of the Bible Lesson 10

The Renaissance, Printing, and the Bible

History of the Bible Lesson 10

The Renaissance, Printing, and the Bible

Renaissance

o What is it?

o The rebirth or re-discovery of classical learning.

o More specifically and especially Greek learning.

o Philosophy, religion, literature, art, etc.

o When was it?

o Scholars disagree, as they always do, on the exact dates (12th, 14th, 15th centuries?).

The European Renaissance of the 15th and 16th centuries that began in

Italy and spread across Europe. It represented both a recovery of a certain

kind of learning and a change in the view of the world.

The

15th Century Renaissance

What Triggered It?

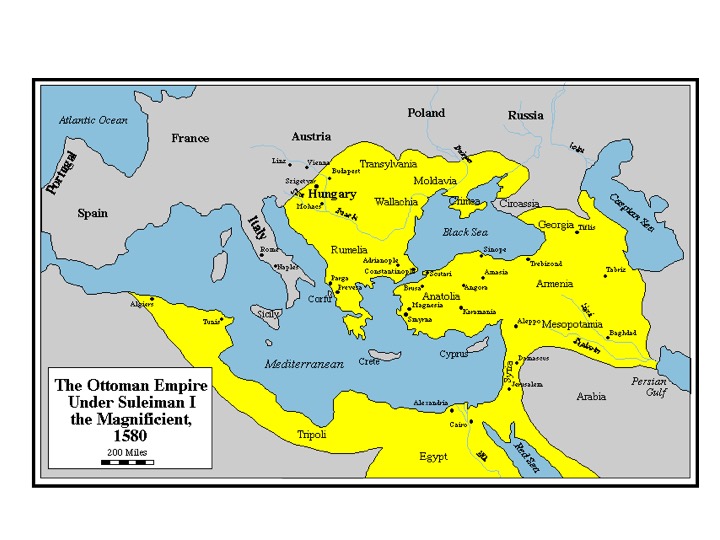

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 meant an emigration of scholars and of Greek and Arabic manuscripts to the West, advancing the recovery of knowledge of Greek language, religion, and philosophy.

A little background on the fall of Constantinople. It fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The Ottoman's were yet another migrating group who had migrated into Asia Minor from the east. The map shows the extent of the Empire they eventually, completely engulfing Constantinople. The yellow territory represents the maximum extent of their territory. The Ottoman Empire lasted until World War 1 before it disappeared.

Recall we discussed in an earlier lesson how the Eastern Roman Empire headquartered in Constantinople remained throughly Greek in its language and culture, and preserved ancient Greek learning in their museums and universities. The western Holy Roman Empire became more and more Latin over time and lost a great deal of Greek learning. But as the Ottoman's approached a now weakened Constantinople the scholarly and highly literate population fled and took much of the Greek literature physically with them to protect it from being destroyed. They escaped predominately to Western Europe.

Thus the scholarly population of western Europe was suddenly made aware of much of the ancient Greek that they had lost over time, as well as the learnings of the Arab world, which had also admired and preserved Greek learning.

The 15th Century Renaissance

1. Scholars could now read Plato not in the Christianized interpretation of Augustine but the original dialogues. Aristotle not in just Aquinas’ use of logic but now the original Nicomachean Ethics.

2. This new knowledge challenged the “medieval synthesis”, which had relied on a unified view of Church and state, of philosophy and theology.

3. With an altered sense of the past came a sense of history and, with a sense of history, the sense of the possibility of change.

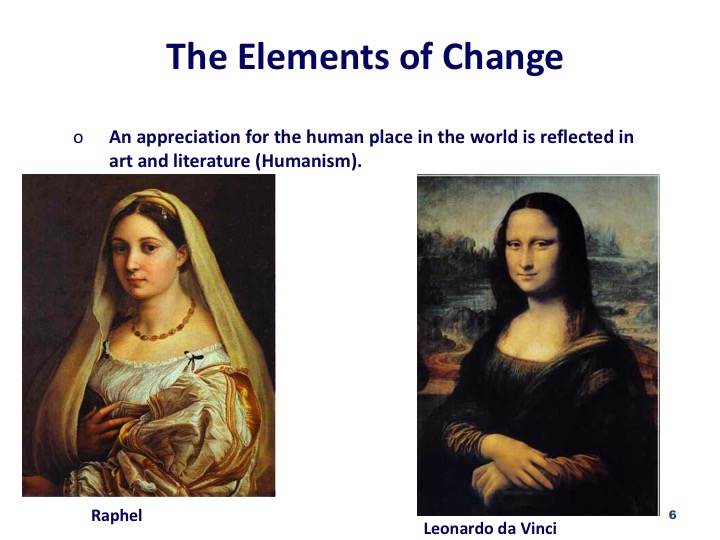

The changes that resulted in the Renaissance was not limited to just literature. There was a rapid change in both art and sculpture. These paintings by Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci are indicative. Humans are now portrayed as humans. The followers of the Renaissance became know as Humanists.

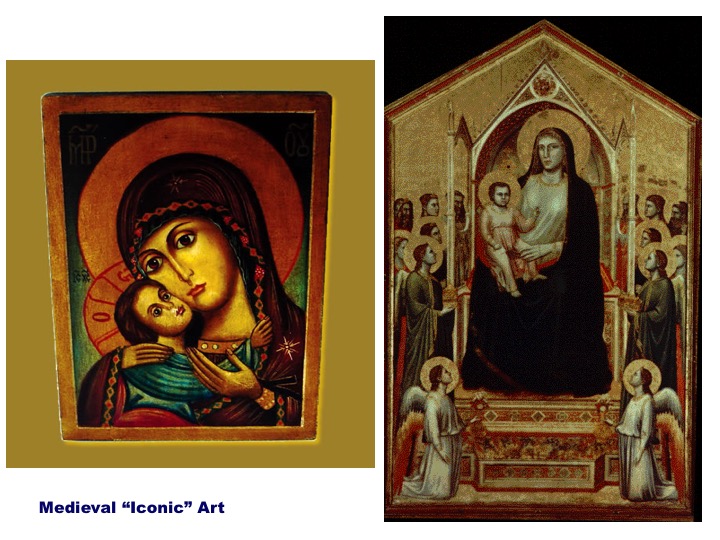

By contrast almost all Medieval art was "iconic". The paintings shown here are indicative. It represented humans but not exactly how real humans looked. And the humans almost never smiled.

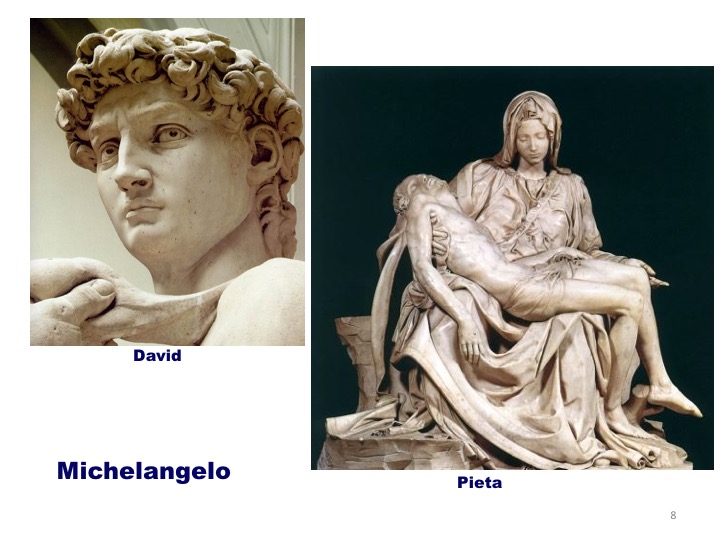

Sculpture was another example, the humanist inclination was to now portray humans in fantastic detail, and in many cases almost erotic beauty.

The Elements of Change

An appreciation for the human place in the world is reflected in art and literature (Humanism).

A sense of possibility and control in the world is seen in the growth in science and technology (Leonardo da Vinci, 1452- 1519).

The development of Italian states was accompanied by theories of politics removed from divine rights (Niccolo Machiavelli, 1469- 1527).

Pico della Mirandola who lived to only 23 wrote (1486) what is often considered the manifesto of the Renaissance, a vibrant defense of thinking, the “Oration on the Dignity of Man”.

Technology

The Invention of Printing

The invention of the printing press in Europe revolutionized the publication and reading of the Bible.

Block printing had been invented in China in 888 (the Diamond Sutra) , as had movable clay type (1041); the first iron printing press was used in China in 1234. Europeans had used xylography (engraving on wood, block printing) by 1423.

But it is Johannes Gutenberg (c. 1398-1468) who is credited with the fundamental contributions to printing in the West. A credit he well deserved because his developments finally made high quality printing very affordable.

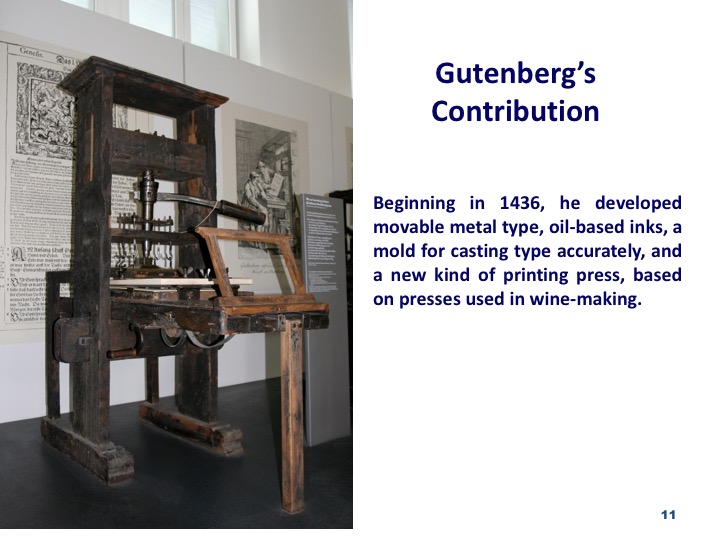

Gutenberg’s Contribution

Beginning in 1436, he developed movable metal type, oil-based inks, a mold for casting type accurately, and a new kind of printing press, based on presses used in wine-making. It was the combination of all of these improvements that made this new version of printing so successful.

Gutenberg’s Bible

Gutenberg’s first moneymaker was printing indulgences. Those get out of purgatory early cards..

In 1450, Gutenberg began work on printing the Bible and published a two-volume version of the Vulgate in 1455, producing 180 copies, 45 on vellum and 135 on paper. Printed, then illuminated by hand.

The first printed Bibles resembled manuscripts, lacking pagination, word spacing, indentation, or paragraph breaks.

Chapter and verse divisions did not appear in printed versions, until added by the Robert Stephanus family of printers, in ~1570.

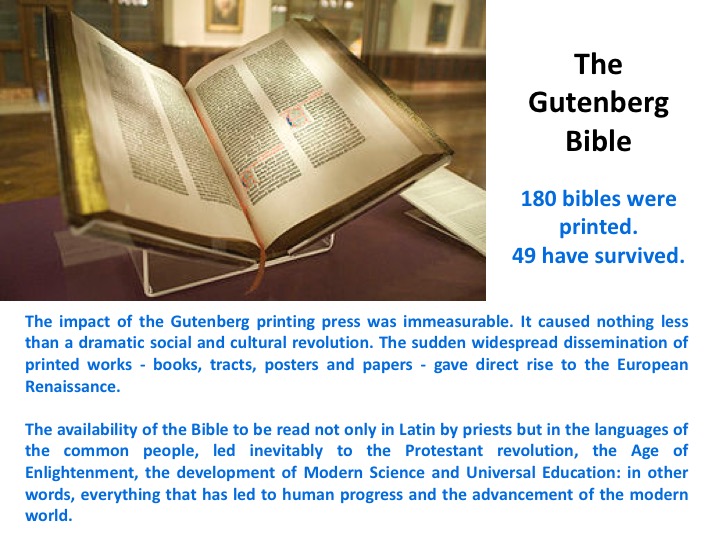

The Gutenberg Bible

180 bibles were printed.

49 have survived.

This one is in the New York public library collection. And Austin has one of the 49 Gutenberg's. It is in the Harry Ransom collection at the University of Texas.

The impact of the Gutenberg printing press was immeasurable. It caused nothing less than a dramatic social and cultural revolution. The sudden widespread dissemination of printed works - books, tracts, posters and papers - gave direct rise to the European Renaissance.

The availability of the Bible to be read not only in Latin by priests but in the languages of the common people, led inevitably to the Protestant revolution, the Age of Enlightenment, the development of Modern Science and Universal Education: in other words, everything that has led to human progress and the advancement of the modern world.

One Last Accolade

What the world is today, good and bad, it owes to Gutenberg. Everything can be traced to this source, but we are bound to bring him homage...for the bad that his colossal invention has brought about is overshadowed a thousand times by the good with which mankind has been favored.

— Mark Twain

How Fast Did Printing Spread?

Gutenberg, a goldsmith by profession, developed a complete printing system that perfected the printing process through all of its stages by adapting existing technologies to printing purposes, as well as making groundbreaking inventions of his own. His newly devised hand mould made possible for the first time the precise and rapid creation of metal movable type in large quantities, a key element in the profitability of the whole printing enterprise.

The printing press spread within several decades to over 200 cities in a dozen European countries. By 1500, printing presses in operation throughout Western Europe had already produced more than 20 million volumes. In the 16th century, with presses spreading further afield, their output rose tenfold to an estimated 150 to 200 million copies. The operation of a press became so synonymous with the enterprise of printing that it lent its name to an entire new branch of media, the press.

Today, the Printing Industry globally is still bringing in revenues of close to 1 trillion US dollars per year.

The Rapid Growth of Printing

The art of printing, which spread rapidly and made books (and Bibles) less and less expensive, had several consequences.

Just as writing created a more stable text than oral tradition, printing offered the theoretical possibility of an absolutely stable and infinitely replicable Bible.

The ready accessibility of the printed text meant that "reading the Bible" could become primarily a visual rather than an oral/aural experience.

The availability of relatively inexpensive books to many meant the possibility of individual ownership and individual reading.

Pushback

Not everyone was thrilled by the rapid spread of this remarkable and very affordable technology.

A group of Benedictine monks, whose livelihood of copying manuscripts was now threatened by the printing press wrote an appeal to their local magistrates to shut down these rapidly spreading printing presses.

“They shamelessly print, at negligible cost, material which may, alas, inflame impressionable youths, while true writers die of hunger and young girls read Ovid to learn sinfulness. Writing indeed, which brings gold for us, should be respected and held to be nobler than all other goods, and not suffer degradation in the brothel of the printing press.”

The

Renaissance and Printing

(And the Quest for a “better”

Bible)

The availability of manuscripts of the New Testament in Greek had much the same effect as the Greek writings of Plato.

The Greek was the earliest and original version, whereas the Latin, however fine, was later and secondary.

The expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492 also opened up the possibility for conversation between Christian and Jewish Humanists concerning the Hebrew text.

Scholars sought to make available a version of the Bible that was more "scientific" than the Vulgate in ordinary use.

The Development of a “Sciencia” Bible

In Spain, Cardinal Ximenes organized a group of scholars at the University of Alcala (Latin: Complutum) to publish the Bible in six volumes (1522), the Complutensian Polyglot.

One of the great Christian Humanists, Erasmus of Rotterdam (1469?-1536), produced-on the basis of a handful of late and mediocre manuscripts-an edition of the Greek New Testament (1516).

The Textus Receptus ("received text") that underlay Luther’s German Bible and the King James Bible was based on versions of Erasmus and the Complutensian scholars, as well as the contributions of the reformer Theodore Beza (1519-1605) and the printer/editor Robert Stephanus.

Scholars

Bible vs. Believers Bible

(An Ongoing Tension)

In the life of the Church, the Vulgate held sway and corresponded to the use of Latin in the liturgy. An undereducated clergy could work only in this version.

In the academy, the scholar had access to versions of Scripture earlier (and perhaps superior) to the one used in the Church: The Hebrew and Greek called into question the absolute authority of the Vulgate.

Soon, there would be an increased demand for Scripture to be available, through the means of printing, in the language of the people.

In Summary

The Renaissance, and it’s new way of looking at history and learning, coupled with the printing press challenged the Medieval Synthesis, challenged the absolute authority of the (Vulgate) Bible and paved the way for change.

And much more change (the Reformation) is on the way.

Next Week

The Protestant Reformation & the Bible