Reading Apostle Paul 3

Paul and Early Christianity

Mike Ervin

Reading Apostle Paul 3

Paul and Early Christianity

In our lesson 1, two weeks ago, you may recall I tried to make the follow point:

“What is most surprising in all the controversy Paul creates is how little attention his critics actually pay to the things with which he was most concerned: the stability and integrity of the tiny Christian communities to which he wrote letters.”

Over the next three weeks we will dig into this issue and try to better understand the things Paul tried to do to ensure the stability and integrity of his many churches. We will start today by looking broadly across all of his letters to ascertain what kinds of problems these churches were having in general and then spend the following two weeks using 1st and 2nd Corinthians as examples of his difficulties with one church he had established, and how he addressed those problems.

Now – it should not come as a surprise that these new tiny communities were struggling to understand exactly who and what they were.

These were very freshly minted communities and it was only a few decades after the resurrection of Jesus. The difficult work to come of defining Christianity, not only it’s beliefs, but its boundary markers, had not yet been done. Where did they fit within a very powerful empire and its accompanying culture and power structures.

You may recall in our recent study of early Christian history that Christianity’s eventual time of self definition did not happen until the latter half of the second century – still a century and a half in the future.

So many of Paul’s churches had fundamental questions because many of the early expectations they had from their initial conversion to the Jesus movement had not fundamentally changed some of their actual reality.

Letter writing was not Paul’s preferred method of communicating with his many communities. He often complained when he could not visit his communities; and when he could not visit in person, he liked to send personal representatives, his delegates. Trusted associates like Titus and Timothy. So they could take the required time necessary to deal with the problems. Then they could report back to Paul with detailed reports on what they had found.

Eventually though, he often was forced to deal with difficult problems via letters.

Because his letters respond to specific situations, they are irreplaceable sources of knowledge concerning the problems experienced among the first urban Christians. In fact they are definitely our prime source of information on the early church. So today will will be reviewing what we have learned about the early church from all of Paul’s letters.

First Missionary Journey (Acts 13–14).

The church at Antioch sent Paul and Barnabas to do missionary work in the West. Their first destination was the island of Cyprus, home of Barnabas (Acts 4:36) and a large Jewish community. They preached in the synagogues. Their crowning success was the conversion of Sergius Paulus (Acts 13:12), the Roman Proconsul of Cyprus.

From Cyprus they set out for Asia Minor, arriving at Perga on the coast, then pressed on quickly to Antioch. Despite initial success preaching in the synagogue in Antioch, Paul found such intense Jewish opposition to the gospel that he determined to turn his message toward the Gentiles (Acts 13:46).

At Iconium, Paul and Barnabas again found opposition from both Jews and Gentiles, escaping a plot to kill them by fleeing to Lystra in the district of Lycaonia. Then Jews from Antioch arrived and organized a mob that stoned Paul, leaving him for dead. After a brief stay, Paul retraced his steps through Lystra, Iconium, Antioch in Pisidia, and Perga, strengthening the believers along the way before returning by sea from the port of Attalia to Antioch in Syria.

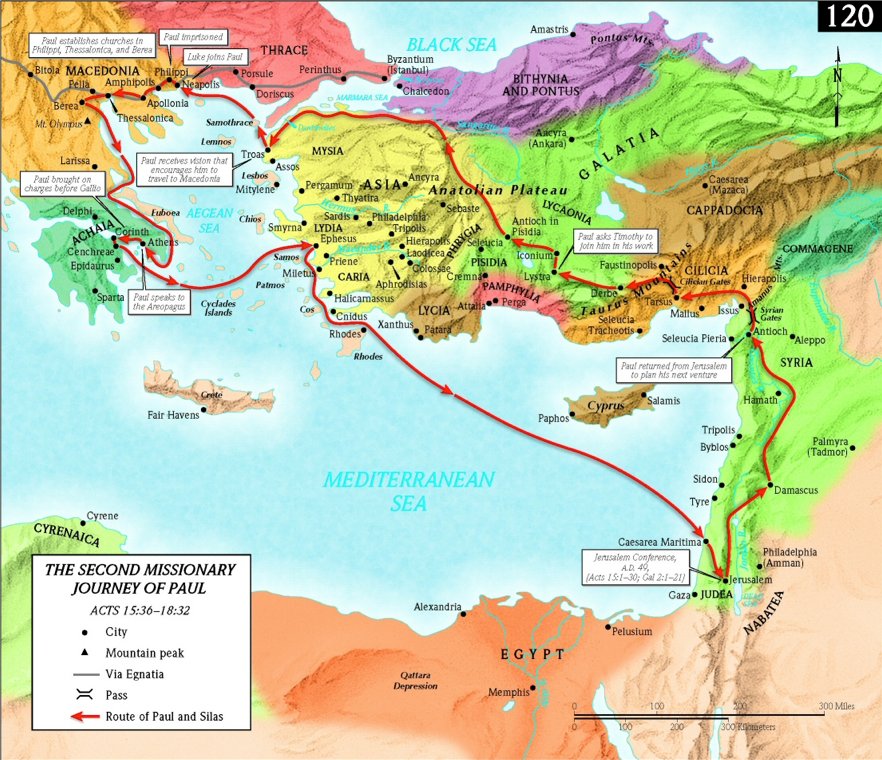

Second Missionary Journey (Acts 15:36–18:22).

Leaving from Antioch again, Paul headed into Galatia, encouraging the churches he had begun there. He traveled across western Asia Minor to the port city of Troas, where Paul received a vision asking him to come to Macedonia. In his first visit to Macedonia, Paul established churches in Philippi, Thessalonica, and Berea.

Paul’s visits tended to cause riots in Macadonia. In Philippi, the local magistrates arrested and beat him, but an earthquake enabled his escape. Moving on the Thessalonica, an agitated mob from one of the synagogues drove them out and they escaped to move on to Berea. Then agitators from Thessalonica arrived and drove them out of Berea. Paul then traveled to Athens, where he famously debated the philosophers. After that he left for Corinth. Paul encountered great resistance in the local synagogue and decided to then focus the reminder of his efforts there to the Gentiles. He remained there 18 months before finishing his ministry by a brief visit to Ephesus and then sailed back to Caesarea near Jerusalem.

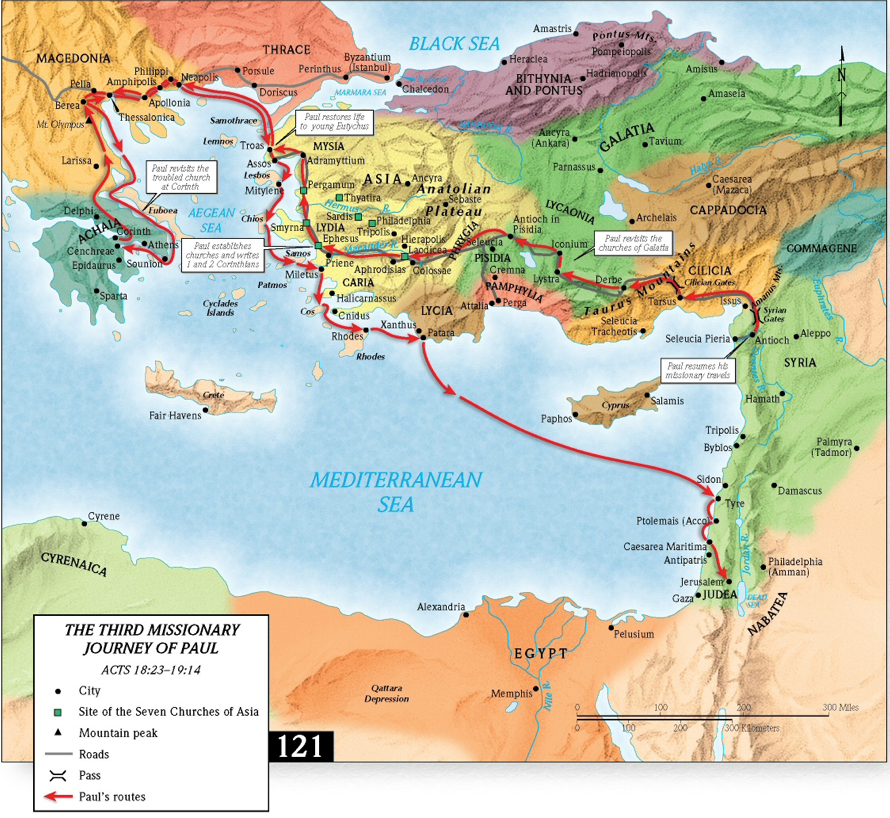

Third Missionary Journey (Acts 18:23–21:14).

After a brief stay in Antioch, Paul again headed back into Asia Minor to visit and strength his previous churches. His main destination was Ephesus, where he spent two years advancing the gospel through many small congregations. It is believe that many of the churches mentioned in Revelations were established during this period. He wrote several letters to other churches during this stay.

Paul then traveled back to Corinth for a 3 month visit to the churches there. When the spring came he intended to sail back to Syrian Antioch, but threats against his life forced him to retrace his path back through Macedonia, with multiple stops, before finally returning back to Jerusalem across the Mediterranean.

The First Age of the Church

Writing about this troubled period of the early church, Edward Gibbon, in ”The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” wrote of a “dark cloud that hangs over the first age of the church”.

Paul, in different churches, was sometimes dealing with a very different religion, now mixed with many concepts and practices rooted in ancient paganism (such mixing of religious beliefs known as syncretism and common in the Roman Empire, took hold and corrupted the new faith.

By late in the first century, as we see from 3 John 1:9-10, conditions had grown so dire that false ministers openly refused to receive representatives of the apostle John and were excommunicating true Christians from the Church!

9 I have written something to the church; but Diotrephes, who likes to put himself first, does not acknowledge our authority. 10 So if I come, I will call attention to what he is doing in spreading false charges against us. And not content with those charges, he refuses to welcome the brothers and even prevents those who want to do so and expels them from the church.

More Scriptural References to the Problems

Acts: 20:29-30 29 I know that after I have gone, savage wolves will come in among you, not sparing the flock. 30 Some even from your own group will come distorting the truth in order to entice the disciples to follow them.

2 Corinthians 11:13-15 13 For such boasters are false apostles, deceitful workers, disguising themselves as apostles of Christ. 14 And no wonder! Even Satan disguises himself as an angel of light. 15 So it is not strange if his ministers also disguise themselves as ministers of righteousness. Their end will match their deeds.

2 Timothy 4:3-4 3 For the time is coming when people will not put up with sound doctrine, but having itching ears, they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own desires, 4 and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander away to myths.

2 Peter 2:1-2 1 But false prophets also arose among the people, just as there will be false teachers among you, who will secretly bring in destructive opinions. 2 Even so, many will follow their licentious ways, and because of these teachers the way of truth will be maligned.

It is hard to overemphasize how “freshly minted” this new religion was.

Barely two decades after the death and resurrection of Christ Paul wrote that many believers were already “turning away . . . to a different gospel” (Galatians 1:6).

He wrote that he was forced to contend with “false apostles, deceitful workers” who were fraudulently “transforming themselves into apostles of Christ” (2 Corinthians 11:13). One of the major problems he had to deal with was “false brethren” (2 Corinthians 11:26).

Church historians label the last decades of the first century as the Age of Shadows because we know so little about it. The next period in which new information emerges is about 120 AD, when the early church fathers begin to write. And at that time there was still no formal system of theology defining the religion. So Paul was faced with dealing with many questions, and usually from a distance through letters.

Consistent Mis-Understandings in the Assemblies

Looking across the churches, we can see some consistent mis-understandings that the early Christians were having.

One could be described as problems with time – when are things going to happen?

Paul and his readers share an apocalyptic framework that sees history as moving toward a climax, which will be God’s visible victory in the world. They share also the recent experience of a strong transforming power through the resurrection of Jesus and their experience of the Holy Spirit. But this has left them with questions:

1. If they are now part of a new creation, why do the powers of the world still dominate?

2. If they have conquered death, why do members of the community still die?

Some Early Church Interpretations

From the tensions created by these unmet expectations, and without Paul there, some of the members were coming up with possible answers:

1.Christ’s resurrection applied only to him, and God’s victory is still far away in the future.

2.Christ’s resurrection has already inaugurated the end-time, but the victory is not in the real world – it is spiritual.

3.Christ’s resurrection has inaugurated the end-time, but it depends on personal transformations of all for the transformation to be compete.

None of these interpretations satisfied Paul, but he had to come up with answers to these concerns.

Other Questions

In addition to issues of time, Paul’s churches had issues of space, more particularly they struggled with identity boundaries with the culture they were engulfed in.

“If we are now ‘saints’, how are we to be different than Jews and Pagans?”

Paul had expressed the ideal of that in Galatians 3:28:

3:28 There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.

Essentially saying that in the Christian community differences that distinguish race, gender, and class in society are to leveled.

But the reality is that the churches struggle to realize this egalitarian ideal as they engage the resistance of cultural realities of everyday life.

Jew/Greek

Is there really no difference between Jew and Greek? There are both theological and practical issues here:

1.Theological – the relationship between their experience of Christ and the Torah. Is the law of Moses an absolute norm for all or has that changed? Either choice has serious implications for salvation.

2.Practical – the issue of Jew/Greek matters for practical life together, especially in the realm of dietary and sexual practice. Don’t we need uniform rules?

Male/Female

Is there really no difference between male and female? Culturally inscribed gender differences are notoriously difficult to erase.

1. Where the Holy Spirit moved women in the worship services - the Pauline Christians tended to ignore gender.

2. But when the activities of the church intersected the rigid patriarchal structures of the Hellenistic household, both Paul and his readers tended to get nervous and repressive.

Slavery

In the highly stratified Roman Empire, in which almost all of the energy required for economic growth was based on slavery, and slavery was a fiercely defended “fact of nature”, can the new movement really eliminate the differences between slave and free?

1. This problem is quite complicated, because the communities all contained members of both classes and because Jesus was sometimes identified early in the tradition as a “servant of God”.

2. So the question that often arose was whether the slave/free egalitarianism of the community to be one of attitude only, or should it be expressed in attempted structural reform.

Rich/Poor

Another polarity, not found in Galatians 3:28, but also experienced as a tension, can be expressed as “neither rich nor poor.”

1. Once more, the presence of the truly poor and the moderately wealthy in Pauline churches complicates the issue.

2. How is a Christian community to resolve an ideology that scorns wealth (“blessed are you poor”) yet needs the support of its wealthier members?

Paul’s Responses

Paul responds to these issues in interesting characteristic ways.

1. He is much more concerned about the stability and health of the community than about theoretical correctness; he privileges the communal over the individual.

2. He respects a plurality of perception and practice without prescribing a universal norm, except when a fundamental principle is involved.

3. He calls for boundaries that are spiritual or moral, rather than spatial or ritual.

4. The measure for moral behavior is what Paul consistently calls the mind of Christ (1 Corinthians 2:16). He wants the members of this community to act in accordance with a new kind of consciousness, which is that found in Jesus Christ. What wold Jesus do?

5. But getting from Christ’s mind to practical decision making requires thinking. And Paul expects the communities to do that thinking. And not rely on Paul to solve all of their problems.

And as we delve into the two letters to the Corinthians we will be on the lookout for how Paul tried to use these characteristic responses.

Upcoming - Next 2 Weeks

1st and 2nd Corinthians

See You Next Week!