Sacred Texts of Islam

Lesson 2

So What’s Next

Last Week

An overview of the Qur’an. Focused primarily on an aspect of the Qur’an that most non-Muslim’s are probably not aware of – it’s Biblical orientation.

This Week

A few finishing thoughts on the Qur’an.

Then we will completely change horses. We cannot study Islamic sacred texts without getting into the broader subject of Islamic law. That will involve non Qur'anic sources and special methods of interpretation not well understood outside of Islam.

Moving Beyond the Qur’an

We now move into new territory. Lesson 1 was primarily getting acquainted with what is in the Qur’an. And we tried to show a few things that most non-Muslims may not have been aware of. Namely that the Qur’an is heavily Bible oriented. The main characters in the narratives are the same ones as in our Bible (Adam & Eve, Noah, Abraham & family, Moses, Mary , and Jesus).

But we also pointed out that in Muslim thinking the Qur’an is also a “corrective”. In Muslim scholarship our Bible is presented as originally divinely inspired but in the final analysis highly corrupted within Judaism and Christianity by misinterpretation and (heaven forbid) translation into other languages down through history.

Moving Beyond the Qur’an

“Corrections – An Example”

Jesus is presented as the penultimate prophet of God, the Messiah of Israel, the only sinless person, beloved of God. But not divine and not the son of God. The death and resurrection of Jesus is described as untrue, because God would not have allowed such a righteous person to die at the hands of evil. So Jesus was “spirited” to heaven before being killed, thus no resurrection was even needed.

But Jesus will return – and will do battle with and defeat the Anti-Christ. This leads into very complex end times stories leading to the final judgement of all.

The “Style” of the Qur’an

A Negative View

Although within Islam the beauty of the language, particularly in it’s recitation, is always talked about, many modern scholarly critics of the Qur’an are often quite critical of it as sacred literature. Unlike some other sacred literature, which often contain great narrative stories which people can learn from there seems to be little literary structure to the Qur’an. One sura (chapter) does not lead directly into the next and seem to be standalone. There is not a timewise progression as many of the later recitations of Mohammed show up in the early suras.

The Bible is almost 800,000 words long. The Qur’an about 80,000. But many quotable scholars find it a much more difficult read. Edward Gibbon complained about its “endless incoherent rhapsody of fable and precept”. Thomas Carlyle said that it was “as toilsome reading as I ever undertook; a wearisome, confused jumble, crude, incondite”.

Reading Suras

Sura 1 (“The Opening”):

In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate. Praise belongs to God, the Lord of all Being, the All-merciful, the All-Compassionate. The Master of the Day of Doom. Thee only we serve: to thee alone we pray for succor. Guide us in the straight path, the path of those whom thou has blessed, not of those whom Thou are wrathful, nor of those who are astray.

Reading Suras

Sura 75 (“The Resurrection”):

Yes indeed! I swear by the Day of Resurrection! Yes indeed! I swear by the soul that remonstrates! Does man imagine We shall not reassemble his bones? Indeed. We can reshape his very fingers! In truth man wishes to persist in his debauchery: He asks when the Day of resurrection shall come. When eyes are dazzled, and the moon is eclipsed. And the sun and moon are joined together. Man that day shall ask: Where to escape?” No, there is no refuge!

Reading Suras

Sura 82 (“The Splitting”):

When heaven is split open, when the stars are scattered, when the seas swarm over, when the tombs are overthrown, then a soul shall know its works, the former and the latter. O Man! What deceived thee as to thy generous Lord who created thee and shaped thee and brought thee symmetry and composed thee after what form He would?

Reading Suras

Sura 24 (“Verse of Light”):

God is the light of the heavens and the earth. The parable of his light is as if there were a niche and within it a lamp; the lamp enclosed in glass. The glass as it were a brilliant star, lit for a blessed tree, an olive, neither of the East nor the West, whose oil is well-nigh luminous, though fire scarce touched it. Light upon light! God doth guide whom he will to his light. God doth set forth parables for men, and God doth know all things.

Islamic Laws

We now move into a distinctive aspect of Islam - Islamic laws. Unlike most world religions Islam has never made much distinction between religious and secular matters, because all aspects of life should be devoted to God.

After Muhammad became both the political and the religious leader in Medina, he received revelations from God having to do with laws and regulations. These suras, which actually appear toward the beginning of the Qur’an, address such topics as gambling, marriage, inheritance, infanticide, property rights, criminal law, the rights of orphans, and so forth.

Islamic Laws from the Qur’an

Much attention has been given to laws in the Qur’an regarding women. There are several that seem discriminatory by modern standards: A daughter in a family receives only half the inheritance of a son. Yet in the context of 7th - century Arabia, much of what the Qur’an teaches would have been regarded as progressive. Women had some inheritance rights, they were granted protections in divorce proceedings, and they were entitled to control of their own property, even if they were married.

The Qur’an urges both women and men to be modest, but nowhere explicitly requires that women cover their heads or faces. The practice of veiling is more culture-specific; full veiling is rather rare, it happens in some Middle Eastern countries and Afghanistan but most Muslim women live in countries where they can choose whether or not to wear a head scarf (hijab).

Islamic Laws

Such laws and practices, of course, raise the question of interpretation. If all Muslims follow the Qur’an, how can they practice it differently in different countries? Who determines the rules?

Consider, for example, the Qur’anic allowance of polygamy. Polygamy was common in ancient societies, and the Qur’an allows up to four. Interestingly Surah 4:129 seems to discourage polygamy. What is the actual practice? Polygamous unions make up between 1 to 3 percent of all Muslim marriages today, since most Muslims live in countries where such marriages are restricted.

Islamic Laws from the Qur’an

These are a few of the Islamic laws attributed to the Qur’an. There are more but within Islam it was recognized that the Qur’an was quite sparse with laws. It did not provide enough details for regulating a complex society. For help there, Muslims had to turn to the Hadith – the Stories of the Prophet.

Before we get into what the Hadith is and how it is used to generate more laws and regulations in Islam – let’s examine where most Muslims are located today.

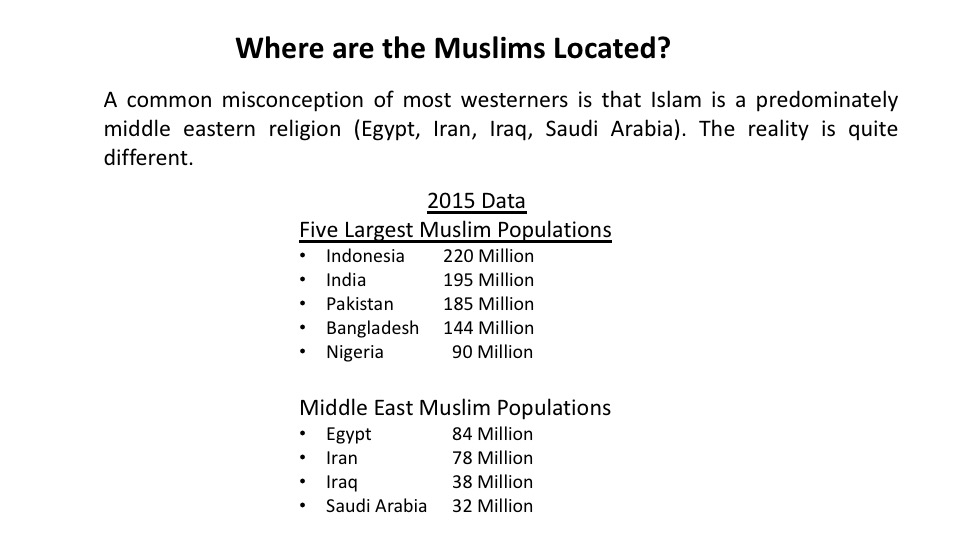

Where are the Muslims Located?

A common misconception of most westerners is that Islam is a predominately middle eastern religion (Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia). The reality is quite different.

2015 Data

Five Largest Muslim Populations

•Indonesia 220 Million

•India 195 Million

•Pakistan 185 Million

•Bangladesh 144 Million

•Nigeria 90 Million

Middle East Muslim Populations

•Egypt 84 Million

•Iran 78 Million

•Iraq 38 Million

•Saudi Arabia 32 Million

The Hadith

One of the ways that Muslims have responded to the message of the Qur’an are through legal interpretation based on the Hadith.

To address some variants in the Qur’anic texts, commentators developed the idea of abrogation—that some of the commandments from God had only temporary application, and those could be superseded by later revelations.

A greater challenge than apparent contradictions was the sparseness of the Qur’an; it doesn’t provide enough details for regulating a complex society. For help here, Muslims turned to the Hadith.

What is the Hadith?

Unlike Jesus, Muhammad was never considered absolutely sinless, but he was nevertheless held up as a model of integrity and good conduct. Believers naturally wanted to follow his example, even in things that might seem relatively minor. There are literally thousands of anecdotes concerning the behavior of the Prophet, and they provide a lens through which to interpret the Qur’an.

For believers who want to know about Muhammad’s life, the Qur’an can be frustrating; it doesn’t have much in the way of biography. God speaks to his messenger throughout, but Muhammad’s name occurs only four times, and incidents in his life are referred to rather than recounted. It is only in the Hadith—some of which are rather lengthy—that we learn about his marriages, his political leadership, or his night journey.

What is the Hadith?

In the first couple of centuries after Muhammad, these stories proliferated wildly, and there was a suspicion that many of them might be fraudulent. For this reason, scholars began to collect and evaluate them in systematic ways. A Hadith came to have two parts: the isnad, or chain of sources, and the matn, or the story itself.

One of the early collectors of Hadith, the 9th-century Persian scholar al-Bukhari, is said to have traveled all over the Middle East in search of stories about the Prophet.

He interviewed 1,000 experts and heard some 600,000 Hadith (many of them variants of one another). Of these, he memorized 200,000 and finally came up with just 2,700 that he thought were unquestionably authentic.

Bukhari published his collection in 97 sections, each devoted to a particular topic, such as faith, prayer, festivals, alms, sales, loans, gifts, war, marriage, and good manners, as well as Muhammad's comments on specific suras from the Qur'an.

What is the Hadith?

Bukhari’s collection is highly regarded by Sunni Muslims. Shia Muslims have different opinions about the reliability of early witnesses and have their own collections of Hadith.

The Hadith are accepted as religiously authoritative, but they are not scripture in the same sense as the Qur’an. The Hadith are accounts of Muhammad’s actions and sayings, but the Qur’an is believed as the direct revelation of God’s words; thus, the Hadith are never recited or used in worship.

The relationship of Hadith to Qur’an is somewhat like Talmud to Torah. Both the Hadith and the Talmud are large collections of oral traditions that are intensely studied to determine rules and regulations for believers. However, the various Talmuds are records of legal debates, while the Hadith are raw materials for legal opinions.

Sharia Law

Both Judaism and Islam have relatively small, closed canons, but the second tier of sacred literature is vast. Eventually, the analysis of Qur’an and Hadith produced Sharia, or Muslim law (“a path to be followed” or “the way”), yet this is not a single law code—it’s more of an ideal for a devout Muslim life—and the exact regulations are different in different countries.

Islam has no hereditary or ordained priesthood; instead, leadership in the community comes from legal scholars who are expert in Sharia.

Eventually, there arose four major schools of Islamic law. When faced with new situations or difficult cases, these scholars would consult the Qur’an, the Hadith, and traditional interpretations of the Qur’an known as tafsir. From these sources— and applying the typical types of reasoning associated with one of the four legal schools—a correct judgment could be made.

Sharia Law

The result of this combination of Quaranic interpretations, accompanied by different Hadiths in different cultures and countries, and then interpreted by one of the four major schools of Islamic law can be confusing to many Muslims but totally baffling to outsiders.

Example - the Ayatollah Khomeini, who led the 1979 revolution in Iran and governed the country until his death, first came to prominence as an Islamic legal scholar.

In 1984, a translation of 3,000 of his rulings on everyday life was published, called “A Clarification of Questions”.

This work addressed such topics as flossing, artificial insemination, and organ donation.

Sharia Law in the Modern Era

In the modern era, traditional laws in the Muslim world have been widely replaced by statutes inspired by European models.

While the constitutions of most Muslim-majority states contain references to sharia, its classical rules were largely retained only in personal and family law among Muslim families.

In the late 20th century there was a a strong call for full implementation of sharia law in predominately Muslim countries by more radical Islamist movements. While it attracted international attention, there has not been significant change to date.