The Ancient Near East and Genesis

Lesson 3

Mike Ervin

Reading the Book of Genesis

OK – we are now (finally) turning to Genesis. We spent two weeks trying to show you that “religion in ancient Israel did not exist in a vacuum, but was influenced by the Near Eastern culture around it as much as it in turn influenced that culture” – which was a direct quote that we began with from Andy Dearman.

And we alluded to the possibility the people of ancient Israel that gave us Genesis were also exposed to a great deal of religious literature from surrounding cultures, and that possibly may have influenced some of the writing of Genesis.

And we will review a few of those influences today. But we will also today teach that although there were some influences; the religious literature of ancient Israel was in many ways distinctly different from the religious literature of the surrounding cultures.

Reading the Book of Genesis 2

First point – Genesis is ancient literature. It was written about 3000 years ago in a far away land, in a culture we do not really understand, in an ancient language called Hebrew that we are still learning about. And it was written in a narrative style. It is in a sense a collection of stories – stories most of us know very well because we grew up learning them.

A second and important point. Genesis is written in prose. The significance of that is all the other religious literature of the ancient near east was written in poetry. But the ancient author of Genesis rejected poetry as unsuitable for telling their story.

Third - Genesis explains the worship of a single deity. Which was revolutionary in the ancient near east. But it also presents its ideas on the relationship of God to nature, to the human race in general, and to the people Israel in particular in ways that are, however, foreign to the expectations of most modern readers.

Reading the Book of Genesis 3

Fourth - Genesis is presenting a new worldview, and the vehicle through which Genesis conveys its worldview is not a theological tract, not a rigorous philosophical proof nor a confession of faith. That vehicle is, instead, narrative.

The theology must be inferred from stories, and the lived relationship with God takes precedence over abstract theology. Those who think of stories (including mythology) as fit only for children not only misunderstand the thought-world and the literary conventions of the ancient Near East; they also condemn themselves to miss the complexity and sophistication of the stories of Genesis. For in that thought-world people tried to understand their world through the explanations of mythology – not modern science. These narratives have evoked interpretation upon interpretation from biblical times into our own day and have occupied the attention of some of the keenest thinkers in human history.

Reading the Book of Genesis 4

So, what is the real message of Genesis. This is a tough one because the message must be inferred from narratives (stories).

Many modern readers try to read moral lessons and lessons about how to be saved into Genesis.

But most scholars today are in pretty strong agreement that Genesis was only about revelation.

The author or authors were trying to reveal to the ancient Israelites the nature of their God and how their God was completely different from the gods of all of the polytheistic religions they were surrounded by. And also trying to reveal to them who they were and their special covenant with the only God worthy of being worshiped.

The Creation Story

I have mentioned a few times that Genesis was a breakthrough in religious literature. To give you a feel for that let’s begin with the story of the creation of the world. As we showed earlier there was another famous version of creation from one of the polytheistic religions of Mesopotamia. That was the Enuma Elish – recovered from the King’s library in Nineveh and believed to have appeared in cuneiform in about 1750 BCE.

The Enuma Elish – unlike the Genesis creation story – is a very long mythic poem – written in the Accadian language on seven clay tablets.

The story is extremely complex. Numerous gods are involved and many of them ending up killing each other until Tiamat – the goddess of salt water is killed by her son Marduk and he splits her in half to form the earth and skies.

The Creation Story 2

So how was Genesis different than many of these previous creation stories like “The Enuma Elish”?

We mentioned last week that these other creation stories tended to be highly metaphorical poetry.

And many scholars have commented that the writers of the creation story in Genesis 1 deliberately wrote it as a polemic against the Enuma Elish by making Genesis 1 tightly constructed, and limited in scope but still metaphorically teaching the important things about their God, while not mentioning any other gods.

Genesis 1:1-5

1 When God began to create the heavens and the earth— 2 the earth was without shape or form, it was dark over the deep sea, and God’s wind swept over the waters— 3 God said, “Let there be light.” And so light appeared. 4 God saw how good the light was. God separated the light from the darkness. 5 God named the light Day and the darkness Night. There was evening and there was morning: the first day.

There was a lot of communication in very few verses. How would the Israelites have understood this? Notice first that when God “began” the earth was already there, but without shape or form, so it describes the state of the world as God was beginning – it was unformed, it was void, there was darkness over the deep, and there was a wind from God.

It is describing that which was pre-existent. And how would the early Israelites have heard this list of pre-existent things?

Genesis 1: 2

2 the earth was without shape or form, it was dark over the deep sea, and God’s wind swept over the waters.

In the culture of the ancient near east three of these things are bad, evil. If something is without shape or form it is not good. This is sometimes defined as chaos. Darkness? All ancient people were fearful of darkness – it was frightening and dangerous. The deep sea in their culture referred to the great salt water ocean – the Mediterranean – it was hazardous, risky, treacherous. People who tried to cross it were afraid.

How do we know this – because all of the literature of the ancient near east – much of which predated Genesis – all identified these things as evil – to be avoided. The listeners or readers of this story would have instantly recognized this.

And the wind from God – that was a good thing – because God was good. And God’s role was to bring goodness into this chaotic and evil world.

Genesis 1: 1-5

1 When God began to create the heavens and the earth— 2 the earth was without shape or form, it was dark over the deep sea, and God’s wind swept over the waters - 3 God said, “Let there be light.” And so light appeared. 4 God saw how good the light was. God separated the light from the darkness. 5 God named the light Day and the darkness Night.

And once verses 1-2 made it clear what was pre-existent and evil, God begins God’s creative work in verse 3: “Let there be light”. And so light appeared. Light is the antithesis of darkness – light is good. We know that because verse 4 makes that clear. Then the creative work continued, and God separated the light from darkness.

And finally, God named things. In the ANE, gods of the polytheistic religions named things as they were created.

Genesis 1: 1-5

Now what is going on here in verses 1-5. The beginning of the story may be seeking to explain the question of evil in the world. This is a theological issue that all religions must answer.

For the polytheisms of the ancient world, there was a simple answer because there were plenty of gods to go around, and some of these were evil gods capable of inflicting great harm on humans. They are the source of evil.

For Israel, by contrast, this was a major problem, because only one God is worshipped, and that god, by definition, is a good God. Thus, this story gets God "off the hook," as it were, for the existence of evil in the world. He cannot be blamed, because evil is preexistent. God brought only goodness into the world.

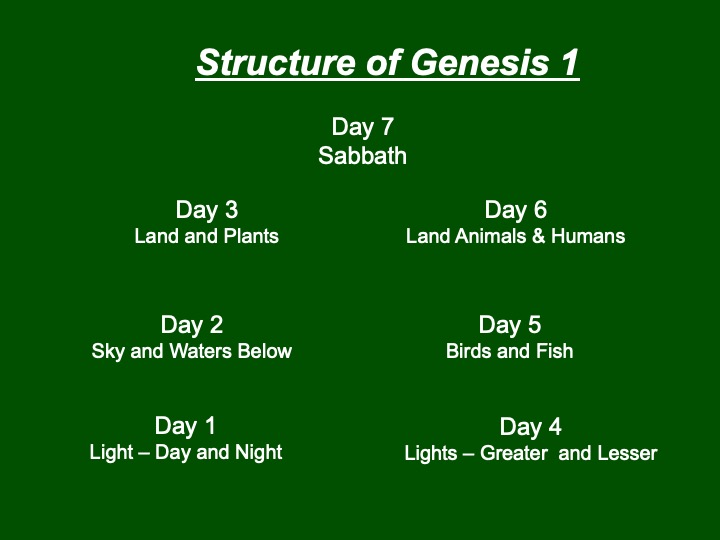

Structure of Genesis 1

The six days of creation are aligned according to a pattern, with the first three days paralleled by the second three days.

There are two stages of creation in day 3-first, the dry land, then, the vegetation-corresponding to two stages of creation in day 6- first, the land animals, then mankind, both of whom inhabit the dry land and eat the vegetation.

This pattern acts as a blueprint and establishes the overall theme of Genesis 1, namely, creation of the world according to an order, representative of goodness, continuing the theme of order out of a chaos, or good out of evil.

And More Structure

Literary refrains appear throughout the text, bolstering the orderly pattern just noted:

A. "And God said, 'Let [such and such happen].'"

B. "And God saw that it was good."

C. "And it was evening and it was morning."

We note, however, that the second of these is missing in day 2. The reason for this is that the second day deals with the separation of the waters into the waters above and the waters below. Because the watery mass is symbolic of evil, as noted above, the refrain must be omitted. That is to say, the author sacrificed literary perfection here in order to make the theological point.

The Gilgamesh Epic

The epic was scribed onto 12 clay tablets. It may be the oldest surviving copy of ancient literature – believed to date from the 18th century B.C. Gilgamesh was a young King who watched his friend die in battle and realized that he too would die some day. The rest of the story was his quest to achieve eternal life.

He eventually meets Utnapishtim, the only immortal man. Who tells him the story of the great flood. Utnaptishtim tells him that he is immortal only because he survived the great flood and one of the gods gave him eternal life because of his bravery in the flood.

Gilgamesh Epic 2

The Gilgamesh Epic was the literary classic of the ancient Near East, read far and wide, either in the original Akkadian (Babylonian) by people educated in that language (even if it was not their native tongue) or in translations into other languages (Hittite, Hurrian, and so on).

This lengthy (by ancient Near Eastern standards) composition is an epic poem about the search for immortality of the legendary king Gilgamesh (from the southern Mesopotamian city of Uruk).

Among the scenes narrated toward the end of the epic is Gilgamesh's visit to Utnapishtim, the flood hero, who relates to Gilgamesh the story of the flood (occurring in Tablet XI of the 12 - tablet composition).

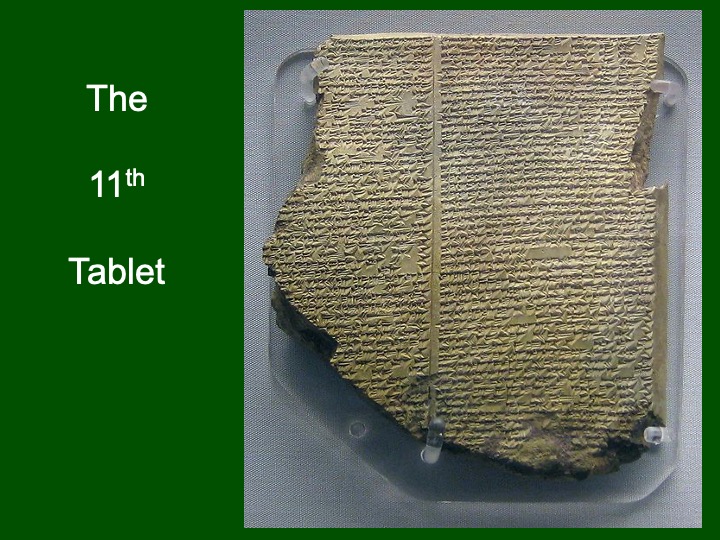

The 11th Tablet

This is the famous 11th (of 12) tablet of the Gilgamesh epic. It is written in Cuneiform. It was discovered in Iraq in about 1878.

There is an interesting human interest story here. A remarkable layman named George Smith, was the first person to realize there was this remarkable flood story, because the 11th tablet was one of the last ones uncovered. Smith was strictly an amateur – his day job was as an engraver. But he became so interested in the discoveries pouring in from Iraq from the excavations of the ancient city of Ninevah – the ancient capital of Assyria – that he taught himself how to read the ancient Cuneiform script in the Akkadian language and volunteered to translate the tablets as they arrived at the British Museum in London. As he worked into the night he realized this tablet was part of the Gilgamesh epic and for the first time read the flood story. He described later in his memoirs the excitement he felt as he read about the birds being sent out from the boat and realized how similar that was to the biblical account.

Now – it has become popular since that time to state that the Gilgamesh epic is so similar that the biblical story was copied from it. And as you might expect there is a counter argument that the Gilgamesh flood story was copied from the Israelite version. But being a natural cynic I always go read them myself. I have the English translation of the Gilgamesh epic and of course I have read the biblical version many times. And I can tell you that there are definitely some similarities that suggest there was a flood tradition in Mesopotamia that was similar to the Genesis flood story but it takes some real imagination to believe there was any exact copying done in either direction.

So we are now going to do some comparisons to show where they are close but frankly not as close as some have suggested. And we will show where they are different.

The Biblical Flood

Now – we cannot possibly read all of the Biblical flood story in detail along with the Gilgamesh epic. But I have excerpted some of the critical texts from both to show you how they compare. And don’t worry – I will be reading Gilgamesh in English - not Akkadian. Let’s start with the instructions God gave to Noah for building the ark.

Genesis 6:14 So make yourself an ark of cypress wood; make rooms in it and coat it with pitch inside and out.15 This is how you are to build it: The ark is to be three hundred cubits long, fifty cubits wide and thirty cubits high. 16 Make a roof for it, leaving below the roof an opening one cubit high all around it. Put a door in the side of the ark and make lower, middle and upper decks.

The Gilgamesh Flood

Here is the instructions Utnapishtim received from the god who told him to build a boat.

O man of Shuruppak, son of Ubartutu:

Tear down the house and build a boat!

Abandon wealth and seek living beings!

Spurn possessions and keep alive living beings!

Make all living beings go up into the boat.

The boat which you are to build,

its dimensions must measure equal to each other:

its length must correspond to its width.

Note there is no mention of the materials – although later we learn that there were carpenters hired by Utanapishtim and bitumen was carried on board so we might assume that wood and pitch were some of the materials. There was also a mention of reed carriers – so possibly reeds were used.

The Biblical Flood

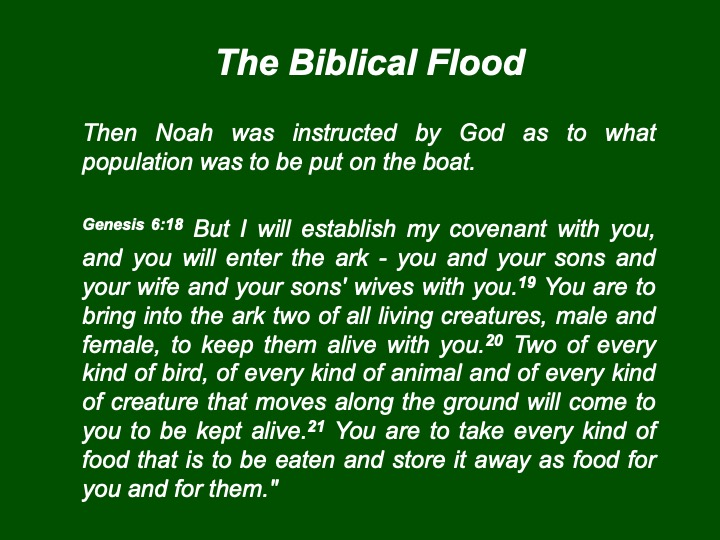

Then Noah was instructed by God as to what population was to be put on the boat.

Genesis 6:18 But I will establish my covenant with you, and you will enter the ark - you and your sons and your wife and your sons' wives with you.19 You are to bring into the ark two of all living creatures, male and female, to keep them alive with you.20 Two of every kind of bird, of every kind of animal and of every kind of creature that moves along the ground will come to you to be kept alive.21 You are to take every kind of food that is to be eaten and store it away as food for you and for them."

The Gilgamesh Flood

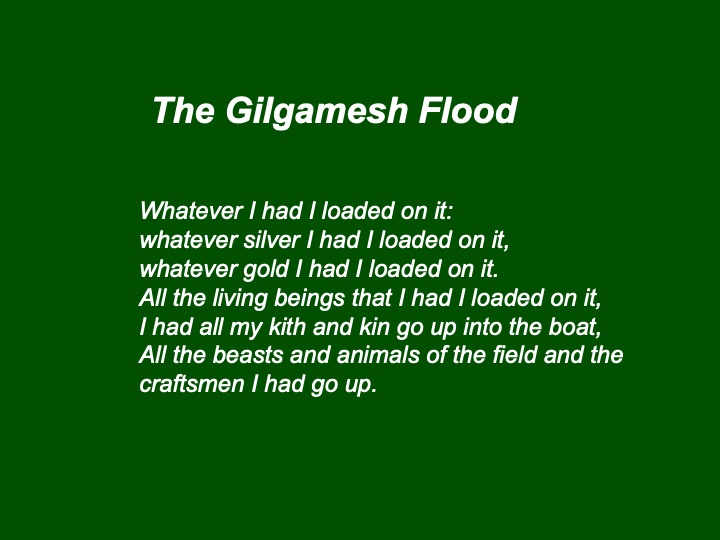

Whatever I had I loaded on it:

whatever silver I had I loaded on it,

whatever gold I had I loaded on it.

All the living beings that I had I loaded on it,

I had all my kith and kin go up into the boat,

All the beasts and animals of the field and the craftsmen I had go up.

It appears that Utnaptishtim did load up people and animals onto the boat – after he loaded all the gold and silver that he could muster.

The Biblical Flood

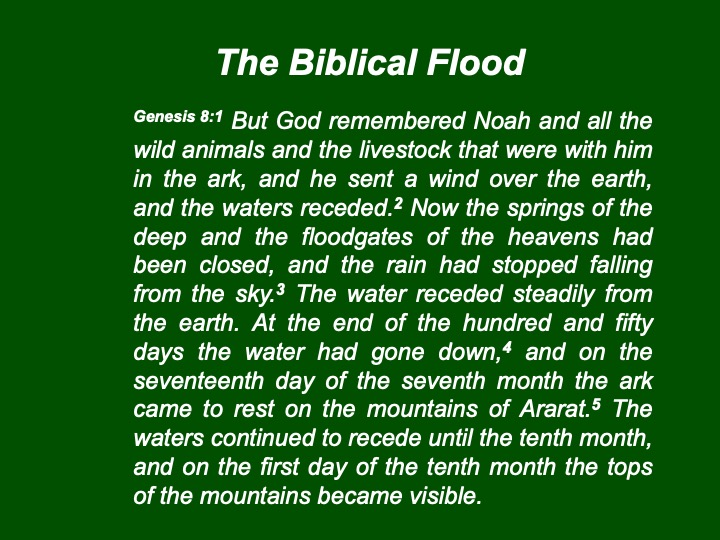

Then we come to the climax of the flood – the great moment when the rains finally stopped.

Genesis 8:1 But God remembered Noah and all the wild animals and the livestock that were with him in the ark, and he sent a wind over the earth, and the waters receded.2 Now the springs of the deep and the floodgates of the heavens had been closed, and the rain had stopped falling from the sky. 3 The water receded steadily from the earth. At the end of the hundred and fifty days the water had gone down,4 and on the seventeenth day of the seventh month the ark came to rest on the mountains of Ararat.5 The waters continued to recede until the tenth month, and on the first day of the tenth month the tops of the mountains became visible.

The Gilgamesh Flood

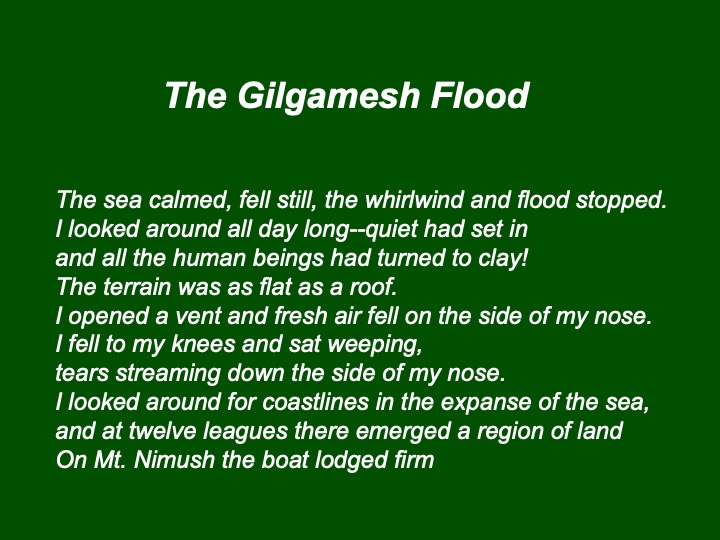

The sea calmed, fell still, the whirlwind and flood stopped.

I looked around all day long--quiet had set in

and all the human beings had turned to clay!

The terrain was as flat as a roof.

I opened a vent and fresh air fell on the side of my nose.

I fell to my knees and sat weeping,

tears streaming down the side of my nose.

I looked around for coastlines in the expanse of the sea,

and at twelve leagues there emerged a region of land

On Mt. Nimush the boat lodged firm

The Biblical Flood

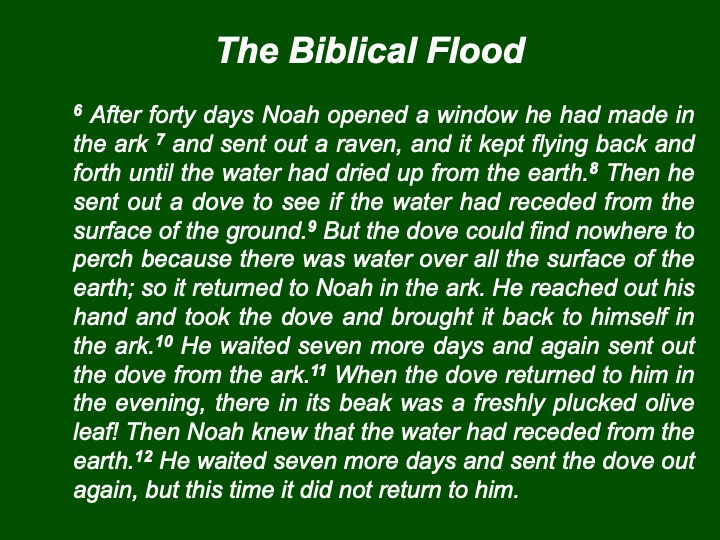

Now we see the critical episode of the birds.

6 After forty days Noah opened a window he had made in the ark 7 and sent out a raven, and it kept flying back and forth until the water had dried up from the earth. 8 Then he sent out a dove to see if the water had receded from the surface of the ground. 9 But the dove could find nowhere to perch because there was water over all the surface of the earth; so it returned to Noah in the ark. He reached out his hand and took the dove and brought it back to himself in the ark. 10 He waited seven more days and again sent out the dove from the ark. 11 When the dove returned to him in the evening, there in its beak was a freshly plucked olive leaf! Then Noah knew that the water had receded from the earth. 12 He waited seven more days and sent the dove out again, but this time it did not return to him.

The Gilgamesh Flood

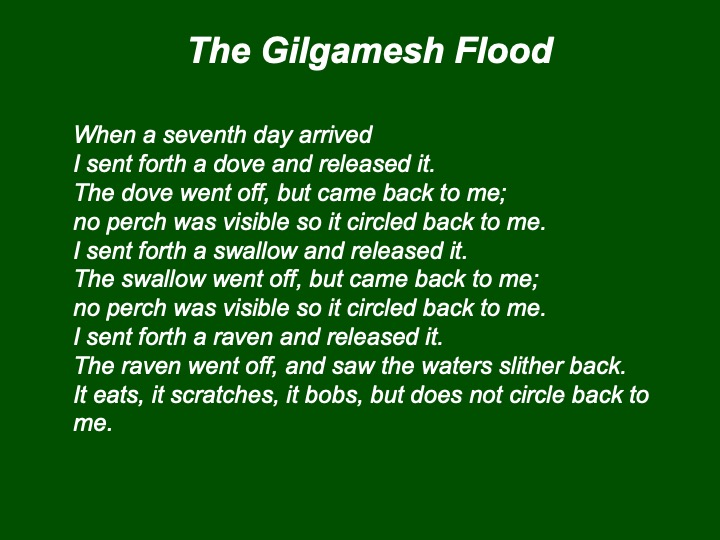

And the remarkably similar bird episode in Gilgamesh.

When a seventh day arrived

I sent forth a dove and released it.

The dove went off, but came back to me;

no perch was visible, so it circled back to me.

I sent forth a swallow and released it.

The swallow went off, but came back to me;

no perch was visible, so it circled back to me.

I sent forth a raven and released it.

The raven went off and saw the waters slither back.

It eats, it scratches, it bobs, but does not circle back to me.

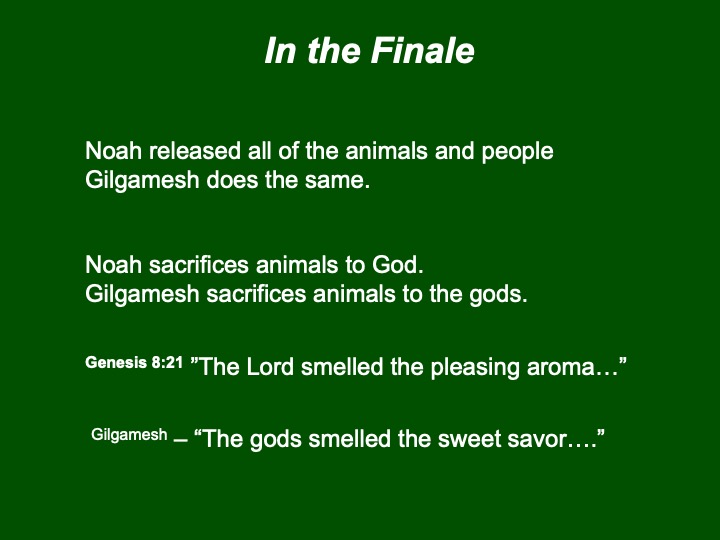

In the Finale

Noah released all of the animals and people

Gilgamesh does the same.

Noah sacrifices animals to God.

Gilgamesh sacrifices animals to the gods.

Genesis 8:21 ”The Lord smelled the pleasing aroma…”

Gilgamesh – “The gods smelled the sweet savor….”

Literary Devices

We move on to literary devices now.

These are techniques that enhance a narrative and increase reader interest.

Maintaining conflict – is a common technique in storytelling. An example used in the Abraham story – the conflict between God’s promises and the reality on the ground that Sarah was barren. It carries on chapter after chapter, hopefully hooking the reader (or listener) into following to find the eventual resolution.

We will spend more time today on the following two devices – the naming convention and style switching.

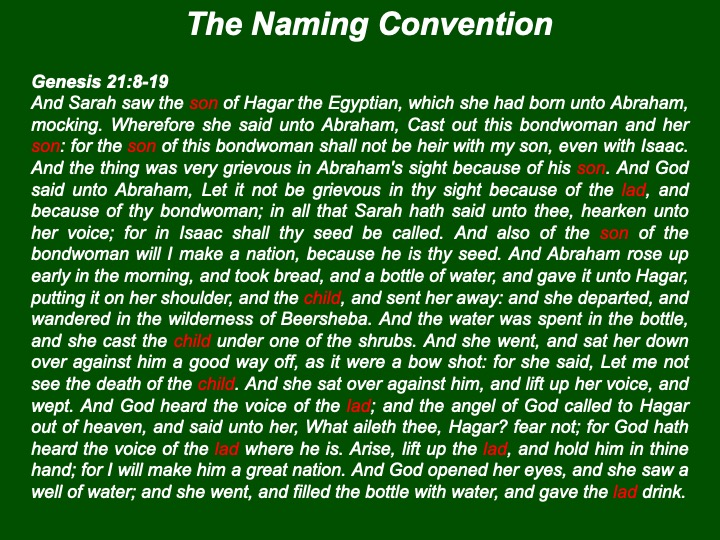

The

Naming Convention

In many ancient traditions, including Jewish and Islamic ones, using or not using a person’s true name can be a powerful thing. The strength of this belief varies, and there are certainly exceptions to it. Nonetheless, the persistence and historical continuity of the linking of naming and power are unmistakable.

Genesis has a startling example of this in Genesis 21 – the story about Abraham and Sarah sending Ishmael away. As seen here in this extended text – suddenly the text stops using Ishmael’s name and instead substitutes the words son, child, and lad. Effectively the Genesis writer is signally to the reader that Ishmael is now being written out of the story.

Style Switching 2

This is a device used in movies and books today. Recall World War II movies that switch scenes between American and German Generals and when the Germans are on screen they continue to speak English but pepper their language with well-known German terms (Herr Commandant, Achtung, etc.) By use of this technique the moviegoer is transported to a different language even though it is still English being spoken.

The writer of genesis used this trick twice – once in the entire chapter 24 and again in chapters 29-31. In both of these episodes a member of Abraham’s tribe visits Padam Aram – the ancestral home of Abraham. Padam Aram is in northern Mesopotamia and the language there is Aramaic – a Semitic language similar to Hebrew but different. And in the original texts (not our English versions) the biblical Hebrew is peppered with Aramaic words that the people of Israel would recognize – thus transporting the readers (listeners) to a new social context.

Such was the skill of the writer of Genesis.

Redactional Structuring

Redactional structuring refers to the manner in which the large sections of the book of Genesis, often composed of disparate units, are organized. We can see this literary technique at work in the three main sections of the patriarchal narratives: the Abraham cycle, the Jacob cycle, and the Joseph story.

We use the term cycle to refer to the Abraham material (Genesis 12-22) and the Jacob material (Genesis 25-35), because those narratives tend to be more a series of individual episodes in these characters' lives, with a connection between and among them not always readily visible.

We use the term story for the Joseph material (Genesis 37-50), because these chapters hold together as one long extended narrative, so much so that some scholars refer to the last section of Genesis as a novella.

All three redactional structures work the same way.

1. The cycle (or story) builds from its onset with a series of episodes in the life of the individual hero (the patriarch).

2. The cycle (or story) reaches a climax, or focal point, halfway through the narrative, on which everything turns.

3. The cycle (or story) concludes with another series of episodes, each of which matches, in reverse order, the episodes in the first half of the narrative.

We call this pattern with inverse order of matching units chiasm or chiastic structure. Let's look at an example with the story of Noah's flood.

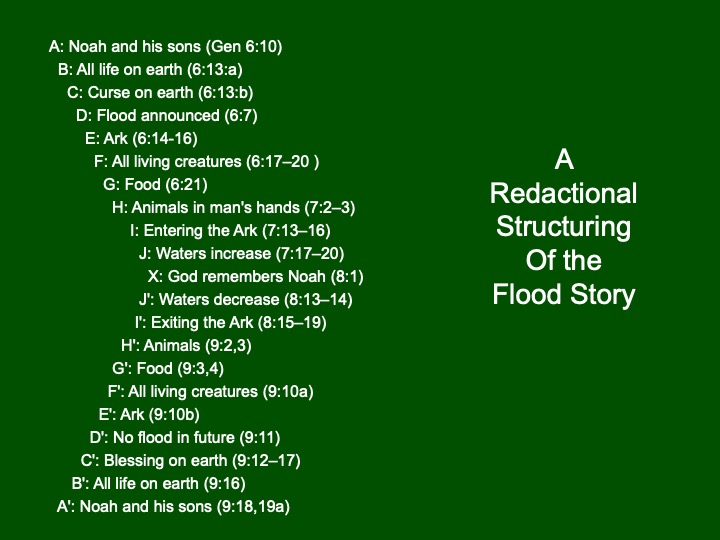

A Redactional Structuring of the Flood Story

A: Noah and his sons (Gen 6:10)

B: All life on earth (6:13:a)

C: Curse on earth (6:13:b)

D: Flood announced (6:7)

E: Ark (6:14-16)

F: All living creatures (6:17–20 )

G: Food (6:21)

H: Animals in man's hands (7:2–3)

I: Entering the Ark (7:13–16)

J: Waters increase (7:17–20)

X: God remembers Noah (8:1)

J': Waters decrease (8:13–14)

I': Exiting the Ark (8:15–19)

H': Animals (9:2,3)

G': Food (9:3,4)

F': All living creatures (9:10a)

E': Ark (9:10b)

D': No flood in future (9:11)

C': Blessing on earth (9:12–17)

B': All life on earth (9:16)

A': Noah and his sons (9:18,19a)

This is the chiastic structure of Genesis 6-9. The first half of this chiastic structure is typically lettered and in this case is lettered from A thru J.

At X we have our focal point or climax. The flood has spent its fury and in Genesis 8:1 the text says: “But God remembered Noah and all the wild animals and the livestock that were with him in the ark, and He sent a wind over the earth, and the waters receded.

It begins with Genesis 6:10 ”Noah had three sons: Shem, Ham and Japheth. ”It ends with Genesis 9: 18b: The sons who came out of the ark were Shem, Ham and Japheth. Followed by 19a: “These were the three sons of Noah”.

We could go on and on but

I think you get the picture. There was an

elegant design to these narratives. The

writer of Genesis invented narrative structure. And one requirement of

narrative structure such as this is the need for repetition – big time. So when the modern literary scholars of the late 20th

century discovered all of this chiastic structure in Genesis many have proposed that all of the repetition observed in Genesis stories is simply required in this type of narrative structure, and it is not a result of the use of multiple sources, which has been the prevailing theory (the JDEP theory) until recently.

The Message?

The result of this analysis is the conclusion that there is much greater literary unity to the book of Genesis than most scholars have realized.

The reader is supposed to see the hand of God in this literary unity. A theological message shines through: There is a divine presence in Israel's history, with the redactional structuring serving as the blueprint.