Rome in 1st Century

Mike Ervin

The Jewish/Christian Situation in Rome

We have been studying Paul’s letter to the Romans, taught by Chris Knepp. That will continue on Nov 28th and Dec 5th.

But for this week (Nov 21st) we will try to increase our understanding regarding what Rome was like in those times with regard to the status of Judaism, recognizing that at that time Rome viewed an emerging new Jewish sect (that we tend to call Christianity) as another of the several sects of Judaism.

If we rely our understanding of Rome at that time on the New Testament, we do not have much to go on. Paul had never been there when he wrote his epistle to the Romans. He had not established any Christian congregations there. And one impression you get in reading the Book of Romans is that Paul was attempting to introduce himself to them. We are told very little about how the situation in Rome vis-à-vis either Judaism or Christianity.

The Jewish/Christian Situation in Rome

Outline

- Timelines

- A Brief History of the Roman Empire before Paul

- Life in Rome

- Roman approach to Judaism

- Roman Catacombs?

Timelines

1000 BCE Latins begin to settle in Italy

753 BCE Legendary founding date of the city of Rome

750-510 BCE Rule of the 7 kings of Rome

509 BCE Foundation of the Roman Republic

390 BCE The Gaul's sack Rome

100-44 BCE Life of Julius Caesar – founder of the Roman Empire

42 – 62 CE Paul’s missionary journeys

50 – 60 CE Establishment of Christian Communities

64 CE Persecution of Christians in Rome

A (little) Roman History

The history of the Roman Empire can be divided into three distinct periods: The Period of Kings (625-510 BC), Republican Rome (510-31 BC), and Imperial Rome (31 BC – AD 476).

Founding (c. 625 BC)

Rome was founded around 625 BC in the areas of ancient Italy known as Etruria and Latium. It is thought that the city-state of Rome was initially formed by Latium villagers joining together with settlers from the surrounding hills in response to an Etruscan invasion. It is unclear whether they came together in defense or as a result of being brought under Etruscan rule. Archaeological evidence indicates that a great deal of change and unification took place around 600 BC which likely led to the establishment of Rome as a true city.

A (little) Roman History

Period of Kings (625-510 BC)

The first period in Roman history is known as the Period of Kings, and it lasted from Rome’s founding until 510 BC. During this brief time Rome, led by no fewer than six kings, advanced both militaristically and economically with increases in physical boundaries, military might, and production and trade of goods including oil lamps. Politically, this period saw the early formation of the Roman constitution. The end of the Period of Kings came with the decline of Etruscan power, thus ushering in Rome’s Republican Period.

A (little) Roman History

Republican Rome (510-31 BC)

Rome entered its Republican Period in 510 BC. No longer ruled by kings, the Romans established a new form of government whereby the upper classes ruled, namely the senators and the equestrians, or knights. However, a dictator could be nominated in times of crisis. In 451 BC, the Romans established the “Twelve Tables,” a standardized code of laws meant for public, private, and political matters.

Rome continued to expand through the Republican Period and gained control over the entire Italian peninsula by 338 BC. It was the Punic Wars from 264-146 BC, along with some conflicts with Greece, that allowed Rome to take control of Carthage and Corinth and thus become the dominant maritime power in the Mediterranean.

A (little) Roman History

Republican Rome (510-31 BC)

Soon after, Rome’s political atmosphere pushed the Republic into a period of chaos and civil war. This led to the election of a dictator, L. Cornelius Sulla, who served from 82-80 BC. Following Sulla’s resignation in 79 BC, the Republic returned to a state of unrest. While Rome continued to be governed as a Republic for another 50 years, the shift to Imperialism began to materialize in 60 BC when Julius Caesar rose to power.

By 51 BC, Julius Caesar had conquered Celtic Gaul and, for the first time, Rome’s borders had spread beyond the Mediterranean region. Although the Senate was still Rome’s governing body, its power was weakening. Julius Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC and replaced by his heir, Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (Octavian) who ruled alongside Mark Antony. In 31 BC Rome overtook Egypt which resulted in the death of Mark Antony and left Octavian as the unchallenged ruler of Rome. Octavian assumed the title of Augustus and thus became the first emperor of Rome.

A (little) Roman History

Imperial Rome (31 BC – AD 476)

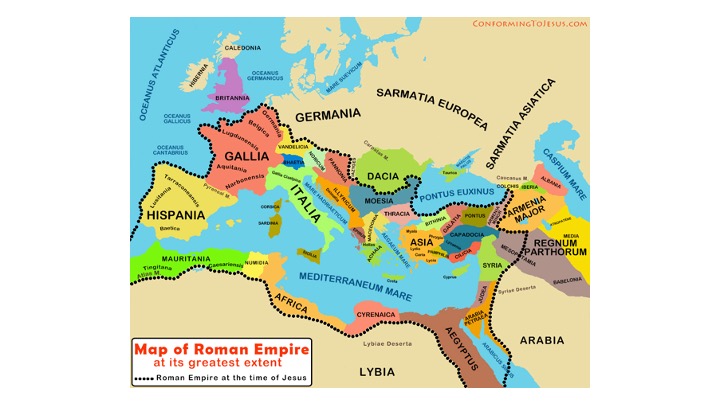

Rome’s Imperial Period was its last, beginning with the rise of Rome’s first emperor in 31 BC and lasting until the fall of Rome in AD 476. During this period, Rome saw several decades of peace, prosperity, and expansion. By AD 117, the Roman Empire had reached its maximum extant, spanning three continents including Asia Minor, northern Africa, and most of Europe.

In AD 286 the Roman Empire was split into eastern and western empires, each ruled by its own emperor. The western empire suffered several Gothic invasions and, in AD 455, was sacked by Vandals. Rome continued to decline after that until AD 476 when the western Roman Empire came to an end. The eastern Roman Empire, more commonly known as the Byzantine Empire, survived until the 15th century AD. It fell when Turks took control of its capital city, Constantinople (modern day Istanbul in Turkey) in AD 1453.

A "preforming map" showing the growth and eventual end of the western Roman Empire. All you have to do is watch it.

The number in the bottom left of the map is the year. So it starts with "minus 510" which represent 510 B.C.E. As that number moves forward you will see the initial growth of the Roman Republic and Empire as it moves forward. When it gets to minus 31 Rome becomes an Empire and quickly grows to its maximun extent in the year 117 C.E. then keep watching and you will eventually see the formation of the Eastern Empire headquartered in Constantinople (green), followed by the encroachment of the Gothic invasions into the Western Empire, which eventually is completely taken over by the Goths (German tribes), leaving finally only the green Eastern Empire, which lasted another 1000 years.

Life in Ancient Rome

Two thousand years ago, the world was ruled by Rome. From England to Africa and from Syria to Spain, one in every four people on earth lived and died under Roman law.

The Roman Empire in the first century AD mixed sophistication with brutality and could suddenly lurch from civilization, strength and power to terror, tyranny and greed.

Leader of the pack

At the head of the pack were the emperors, a strange bunch of men (always men). Few were just OK: some were good - some even were great - but far too many abused their position and power. They had a job for life, but that life could always be shortened. Assassination was an occupational hazard.

The emperors sat at the top of Rome's social order. This was clearly defined pecking order. Specific qualifications were needed for Romans to be admitted as equestrians or senators. Even freed slaves had different rights from citizens.

Life in Ancient Rome

Emperors

The story of Rome’s Emperors in the first century AD has got it all – love, murder and revenge, fear and greed, envy and pride.

Their history is a rollercoaster that lurches from peace and prosperity to terror and tyranny.

Hereditary rule

Why was the first century so turbulent? The first answer is simple: hereditary rule. For most of this period, emperors were not chosen on the basis of their ability or honesty, but simply because they were born in the right family.

For every great leader, such as Augustus, there was a tyrant like Caligula. For every Claudius there was a Nero; for every Vespasian, a Domitian. Only at the end of the period did Rome take the succession into its own hands and select somebody who was reasonably sane, smart and honest.

Life in Ancient Rome

Job for life

Finally, once on the throne, there was no easy exit. Emperors had no elections or term limits, no early retirement or pension plans. It was a job for life, so if an emperor was mad, bad or dangerous, the only solution was to cut that life short. Everybody knew it, so paranoia ruled.

For many, the sacrifices required to get the top job were enormous: Tiberius had to divorce the woman he loved for one he did not; Caligula saw most of his family executed or exiled; Claudius was betrayed and then poisoned by the women he loved.

Although the rewards of power were enormous, many smaller players – like Titus, Galba or Vitellius – barely had time to try on the imperial robes before they died. In the first century, politics could seriously damage your health.

And the Elites

Sitting at the top of Roman society were the emperor and the patrician classes.

Although they enjoyed fabulous wealth, power and privilege, these perks came at a price. As Rome’s leaders, they couldn’t avoid its dangerous power struggles.

Life of luxury

As absolute ruler of Rome and its enormous empire, the emperor and his family lived in suitable style. They stayed at the best villas, ate the finest food and dressed in only the most magnificent clothes.

Life was luxurious, extravagant and indulgent – the emperor’s family could spend their days enjoying their favorite pastimes, like music, poetry, hunting and horse racing.

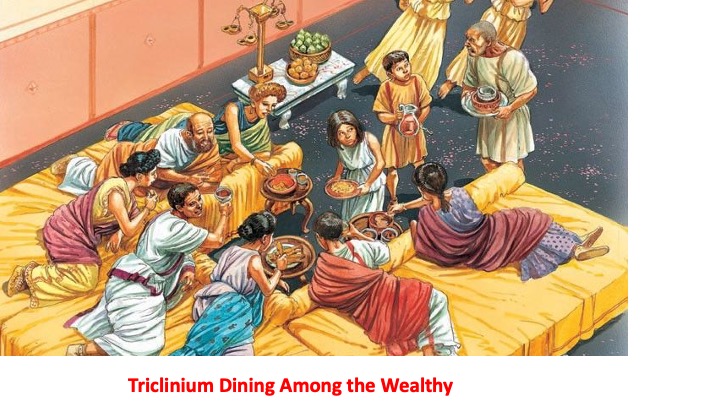

I thought you might be interested in this tidbit. If you were in the wealthy elite you were supposed to eat your evening meal in a certain way to show how special you were. I am not kidding - this is described in detail by Roman historians. This yellow arrangement was known as a Triclinium. And the wealthy ate in this way only. Everyone reclined and rested on their left elbow, leaned forward and picked their "finger food" from a central table. The servants constantly refreshed the table with new food. You never ate from a chair for the evening meal!

And the Elites

Palace intrigue

Still, it was not an easy life. Succession to the emperor was not strictly hereditary: the throne could pass to brothers, stepsons or even favored courtiers and any heir had to be approved by the Senate.

As a result, royal palaces were constantly filled with political intrigue. Potential heirs and their families always needed to be pushing their name, making their claim and hustling for position.

They would have to keep an eye on their rivals for the throne – including members of their own family – and would need to keep tabs on the many political factions within the Senate. Ultimately, to secure the ultimate prize would often require betrayal, backstabbing and even murder. It all made for a very stressful life in which only the strongest and most determined could survive.

And What About Everyone Else?

The ancient Rome that remains today is one of fabulous marble buildings, built with superb skill to enormous scale. It is impressive now – it would have been even more impressive 2,000 years ago.

Sitting next to the grandeur of imperial Rome, however, would have been the tiny, rickety homes of normal people, whose lives were far less fabulous. In truth, daily life in Rome would have been far more like that in modern day Cairo or Delhi than Paris or London.

Most citizens living in Rome and other cities were housed in "insulae." These were small, street-front shops and workshops, whose owners lived above and behind the working area. Several insulae would surround an open courtyard and would, together, form one city block.

The insulae were usually badly built and few had any running water, sanitation or heating. Constructed from wood and brick, they were dangerously vulnerable to fire or collapse. And obviously dangerous to the health of the inhabitants.

And one Roman historian described the insulae as "highly smelly".

The Roman Approach to Judaism

Roman history records the tolerant treatment of Jews in Rome by some Roman emperors. Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) accorded fundamental privileges to the Roman Jews, which facilitated religious observances, by and large, until the political dominance of Christianity in the late fourth century CE.

Among other prerogatives, Caesar granted to the Jews the right to administer their own community affairs; to congregate for worship; to own property, especially for worship and burial; to collect monies for the needs of their communities; to be exempt from military service, so as not to impede their observance of dietary laws and of the Sabbath; and even to have their own courts of justice.

And it is recorded in Roman history that the Jews mourned the assassination of their distinguished benefactor with much weeping at his funeral pyre.

The Roman Approach to Judaism (2)

Caesar's nephew and adopted son, Augustus, emperor from 27 BCE-14 CE, extended the privileges of Jews even further.

Those counted among the poorer residents of Rome were included in the distribution of the annona. "Annona" was the designation for the annual produce of Rome and usually referred to grain, the Roman dietary staple.

Maintaining an adequate food supply was one of the most important Roman government public support projects. When the population in the city of Rome began to expand too fast to be supported by the food sources in Italy, the shortages resulted in rioting by the populace.

In response, Augustus established a system for importing and distributing grain at minimal or no cost to the poor or to public servants.

The Roman Approach to Judaism (3)

Millions of bushels of grain were imported, chiefly from Egypt, Africa, and Sicily. When the distribution was scheduled to take place on the Sabbath, Augustus permitted the Jewish population of Rome to receive their government-issued allotment of money and foods on a day other than their holy day. He also approved the collection of an annual tax by the Roman Jews to be given to the Temple in Jerusalem.

He even arranged, with his wife the Empress Livia and their family, for gifts and daily burnt offerings of a bull plus two lambs to be presented in perpetuity to the Temple.

Most modern scholars argue that the Roman approach to governing was more pragmatic than principled: Augustus and many of his successors were interested in preserving law and order: as long as an activity or a group did not threaten to disrupt the smooth functioning of Roman administration, it would be tolerated.

Examples – Jews in Rome

Certain Roman Jews were prominent enough to be identified by name and documented in the annals of Rome. One such Jew was the freedman Caecilius, who was renowned in Rome during the Augustan period as an eminent author, historian, literary critic, master of rhetoric, and expert on the style of outstanding ancient orators.

Titus Flavius Josephus (37 – c. 100), was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for The Jewish War, who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly descent and a mother who claimed royal ancestry.

He initially fought against the Romans during the First Jewish–Roman War as head of Jewish forces in Galilee, until surrendering in 67 CE to Roman forces led by Vespasian after the six-week siege of Jotapata. Josephus claimed the Jewish Messianic prophecies that initiated the First Jewish–Roman War made reference to Vespasian becoming Emperor of Rome. In response, Vespasian decided to keep Josephus as a slave and presumably interpreter. After Vespasian became Emperor in 69 CE, he granted Josephus his freedom, at which time Josephus assumed the emperor's family name of Flavius.[6]

Flavius Josephus fully defected to the Roman side and was granted Roman citizenship. He became an advisor and friend of Vespasian's son Titus, serving as his translator when Titus led the siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE. Since the siege proved ineffective at stopping the Jewish revolt, the city's pillaging and the looting and destruction of Herod's Temple (Second Temple) soon followed.

Expulsions

On the whole, based on Roman sources, Jews in Rome seem to have fared reasonably well, except for a few events such as the short-lived expulsions under the emperors Tiberius (14-37 C.E.), Claudius (41-54 C.E.), and Domitian (81-96 C.E.).

The expulsion by the Emperor Claudius mentioned above might have happened near the time of Paul’s work. The famous Roman Suetonius reported that there was turmoil within the Jewish community of Rome regarding constant disturbances by the Jews at the instigation of "Chrestus" a name thought by certain scholars to signify some otherwise unknown follower of Christ or the Christian movement. Still considered by the Romans to be part of the Jewish community, the Christians may now have been encountering vociferous opposition within some circles of their former co-religionists. But that is only scholarly guesswork.

Whatever the events that led to his action, Claudius banned meetings of the Jews in Rome, closed a Roman synagogue, and expelled certain persons alleged to be causing provocation

Expulsions (2)

In the book of Acts in the New Testament (Acts 18:1-2) we read of the expulsion of Jews from Rome.

“18 1 After this, Paul left Athens and went to Corinth. 2 There he found a Jew named Aquila, a native of Pontus. He had recently come from Italy with his wife Priscilla because Claudius had ordered all Jews to leave Rome. Paul visited with them.”

As previously reported, there were occasional expulsions of some Jews from Rome for various reasons, but scholars have not found any evidence of the expulsion of all Jews. No such event is mentioned in the histories of Josephus, Tacitus, or Dio Cassius. Dio, in fact, declared the report of wholesale expulsion to be untrue.

The Catacombs of Rome

I want to finish today with a little sidebar story.

We have all heard of the catacombs of Rome, where apparently many Christians often hid away in to hold worship services without Roman or Jewish prosecution.

As many of you may know, these catacombs were real, and heavily used.

Their main service was for burial.

Under Roman law, people could not be buried with the walls of Rome, so the catacombs were outside the walls.

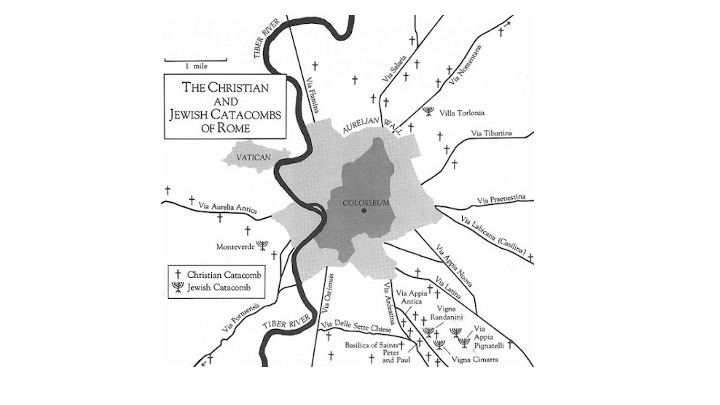

Let’s start with a look at a map of the catacombs.

There is a prestigious scholarly group (with an interesting website) called the Catacomb Society. This is a map they supply of ancient Rome with all the Jewish and Christian catacombs. Only a very small number of these are open to the public.

You can see from the map the symbols that are used to designate the Jewish and Christian websites. All of these are outside the ancient walls of Rome. But they are surprisingly large, many of them are characterized by their size, meaning how many kilometers in length their burial corridors are.

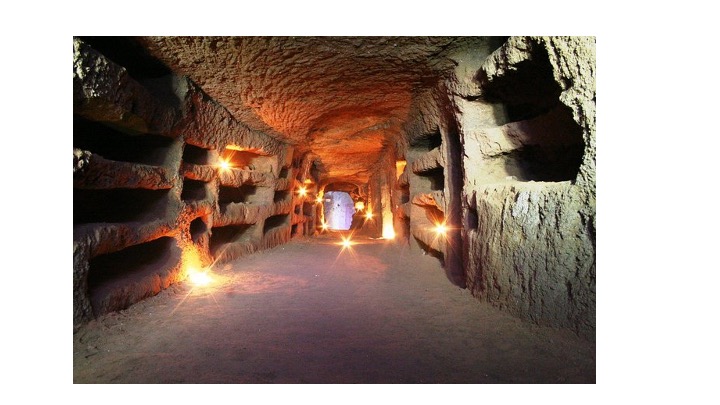

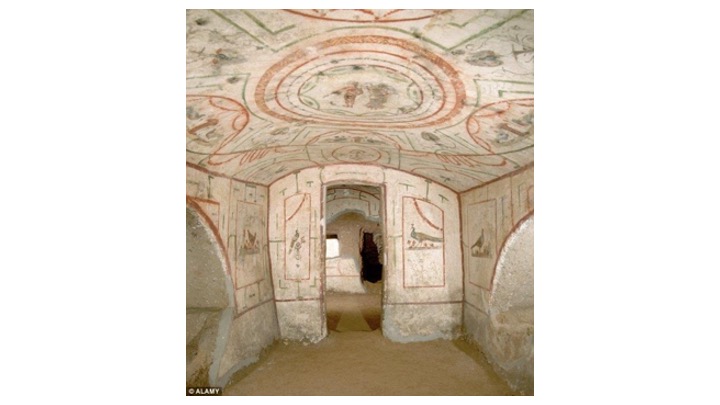

In the remaining slides I show just a few photos taken from some of these.

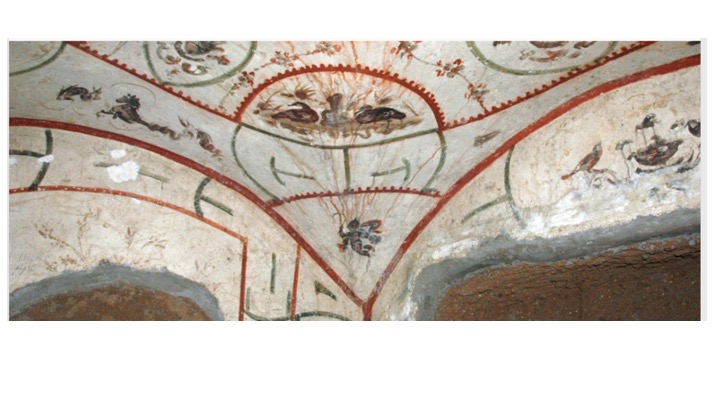

Some of the artwork from a Jewish catacomb.

I believe this is a Christian catacomb. Each of the openings shown held one body. But when originally buried the opening is sealed over and a name put on the cover. In the ones like this one the bodies were later removed because the catacombs were often looted for treasures buried with the deceased by robbers.

A Christian catacomb showing elegant artwork, probably of biblical scenes.

A beautiful example of art from a Jewish catacomb.

Another example of elaborate artwork.

Another very different example from a Paris catacomb. Did I mention that catacombs were not limited to Rome? In Paris the bodies were interred in a different manner and the bodies were not removed. One report I read from a visitor to a Paris catacomb was that it was interesting but "very creepy".

OK - that concludes our lesson but feel free to ask questions.