History of Christianity Class 5

The Shaping of Orthodoxy

Mike Ervin

History of Christianity Class 5 - The Shaping of Orthodoxy

We have surveyed some of the variety to be found in 2nd- and 3rd-century Christianity: prophetic utterances and promises in Montanism; wonder-working in the apocryphal acts, mystical ascent in Gnosticism. But when does diversity become deviance? When are more definite boundaries required? In the middle of the 2nd century, at least partly in response to extreme impulses, Christianity took on a clearer shape. This period represents the most important stage of self-definition for Christianity, when it emerged fully and identifiably as a new religion.

Challenges for Emerging Christianity

A religious movement that began with scattered, diverse, small household groups, held together by certain convictions, practices, and experiences, faced increasing challenges from multiple directions as it grew in size and extent.

From the side of Greco-Roman culture: What elements of the dominant society could Christians affirm, and which ones must they oppose?

From the side of Judaism: In what sense could Christians lay claim to the heritage of Israel?

But the strongest challenges came from within. As we have seen, many versions of Christianity made claims to the experience of power that had always been a distinguishing feature of the movement, but they expressed these claims in sometimes extreme ways; in the eyes of many, diversity threatened to become deviance and division.

• In the face of ever-increasing growth and expansion, the challenge was to secure a framework of the religion that would not only survive but also thrive and adapt to changing circumstances.

Christianity had to figure out how to be a world religion, not just a quirky movement.

History of Christianity

Responses to the Challenges

Coherent responses to each challenge characterized the 2nd century and justified the designation of “the century of Christian self-definition.”

As we saw earlier, the 2nd-century apologists drew the basic line with regard to Greco-Roman culture, accepting its rhetoric and its philosophy (especially that of Plato), which was universally regarded as the philosophy most compatible with biblical perspectives, but utterly rejecting all pagan religion. The apologists adopted a variety of strategies with regard to pagan religion: It was fictional, fraudulent, confused, or even the work of demons who seduced and deceived humans.

What about the boundary with Judaism? Justin Martyr’s Dialogue with Trypho (c. 135) reports a fictive conversation between the Jewish and Christian philosophers. The argument centers on which version of Scripture is accurate and authoritative: the Hebrew or the Greek Septuagint.

Connected to that argument is a dispute over Christ’s fulfillment of biblical prophecy. Trypho insists that the prophecy in Isaiah 7:14 that Christians applied to Jesus was wrongly translated: The Hebrew did not have “a virgin [parthenos] shall conceive” but “a young woman [almah] shall conceive.” Justin responds to the charge that Jesus did not fulfill messianic prophecies: In his First Coming, he fulfilled the prophecies concerning his suffering, but the prophecies about the Messiah’s triumph will be fulfilled in Jesus’s Second Coming.

The relative civility of Justin is lost entirely in Tertullian’s early-3rd-century polemic Against the Jews, which is completely supersessionist in character: Because they rejected the son of God, Jews have lost their status as God’s people; they have been replaced by the “new race” of the Christians.

The most vigorous intellectual and political effort, however, was expended against those called “heretics” by church leaders, who engaged in a “circling of the wagons” around the central elements of the Christian religion. Some of these leaders were bishops; some were not. It is important at this point to recognize that the battle was intellectual and fought with the instruments of rhetoric rather than of formal exclusion.

Tertullian and Irenaeus

Although there were elements of anti-heretical polemic found already in Ignatius of Antioch and Justin Martyr, two figures of the late 2nd century exemplify the effort to establish “orthodoxy” (right teaching) as the measure for Christian membership: Tertullian and Irenaeus of Gaul.

In North Africa, Tertullian (c. 160–225) brought his impressive intellectual energy and persuasive power to the defense of the religion to which he converted.

Tertullian was born a pagan and was well educated in Latin rhetoric and literature. He converted around 197 and may have been ordained a priest. He eventually joined the Montanist sect, which appealed to him because of its asceticism; some of his late moral treatises exhibit its tendencies.

His Apology (addressed to the “rulers of the Roman Empire”) is noteworthy for his plea on behalf of Christianity’s legal recognition, based in its fundamentally philanthropic character. He calls for freedom of religious expression and toleration— but only for Christians!

In other writings, Tertullian turned his rhetorical ability to combating theological error. He argued vigorously against a number of “heretics,” including Marcion and Valentinus. In his response to Praxeas, Tertullian formulated an understanding of the Trinity.

Tertullian’s writing established a technical theological lexicon for later writers.

In Gaul, Irenaeus (c. 130–c. 200) was of even greater significance as a shaper of an orthodox tradition based in tradition and reason.

Probably born in Smyrna, as a young boy, Irenaeus had met the martyr Polycarp. He became a presbyter in Lyons, an important Roman city in Gaul. After the martyrdom of Pothinus (c. 178), in the persecution under Marcus Aurelius, he became bishop of Lyons.

Irenaeus was a conciliatory voice in relations with the Montanists and, later, with the Quartodecimans of Asia Minor. He resisted the effort to excommunicate them.

He wrote an apologetic work (Demonstration of the Apostolic Preaching), but his masterpiece was Adversus omnes haereses (Against All Heresies), written in Greek in five books.

Despite differences in location, language, and temperament, Tertullian and Irenaeus—and many others—shared the conviction that there was a “truth” to Christianity that was not a matter of personal or individual experience but a matter of communal teaching (orthodoxy) and moral behavior (orthopraxy). For them, Christianity was inherently social and institutional in character.

History of Christianity

A Threefold Definition of Christianity

In Irenaeus’s Against all Heresies, we can see the basic instruments that were deployed in the effort to define Christianity in terms of orthodoxy.

Irenaeus himself conceived of Christianity in terms of Greco- Roman philosophy and perceived and described other versions of Christianity in the same terms. Thus, he describes “heresies” (“parties”) in terms of philosophical schools, divided by doctrinal differences.

Following the custom of ancient rhetoric, he mocks the illogicality and inconsistency of opponents’ ideas. He uses noble metaphors for traditional teaching and ludicrous metaphors for his opponents.

Positively, he provides what he regards as a better reading of the texts and traditions he thinks others are misreading. Thus, Paul’s language about “flesh” versus “spirit” in his Letter to the Galatians is not cosmological—pointing to an internal split between body and soul—but ethical—pointing to ways of conducting one’s life.

It is, above all, Irenaeus’s strategy of self-definition that makes his work of such enduring value. He argues for a threefold approach to tradition: the canon of Scripture, the rule of faith, and the authority of bishops.

Because of the proliferation of literature—much of it claiming to be “revealed”—it was necessary to establish the canon (“rule/ measure”) of compositions that could be used to define Christian teaching and practice. In his rebuttal of the Gnostics, Irenaeus named his sources from the Old and New Testaments, indicating which were truly authoritative and which were to be rejected.

Irenaeus also drew on a developing tradition of a rule of faith (or creed) to provide a doctrinal framework for Christian identity.

Elements of a creed are found already in Judaism (“Hear O Israel, the Lord your God is One God”) and in the New Testament, where Paul tells the Corinthians, “… for us there is One God, the Father, from whom all things come and for whom we are; and one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom everything was made and through whom we are” (1 Cor. 8:4–6). Inherent even in the basic claim “Jesus is Lord” is a statement of belief.

Irenaeus’s rule of faith is similar to the so-called Apostles’ Creed, which presents an epitome of scriptural witness; as such, it also provides a guide to reading the canonical Gospels: This is the truth that readers are to find in those complex texts.

In addition to canon and creed, Irenaeus asserts the historical priority of an “apostolic succession” of bishops, whom, he argues, read only these books and believed these things from the time of Jesus until the present.

The notion of the bishops as the successors of the apostles is found already in Clement of Rome, but Irenaeus argues it more fully, with specific attention to the bishops of Rome from the time of Peter down to the present bishop.

This institutional argument directly opposes the Gnostic position concerning secret teachings, secret teachers, and secret books.

• The principle of episcopal leadership is displayed in the so-called Quartodecimans (Easter) controversy in which Irenaeus was involved. It is narrated by Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical History (1: 502–513).

Bishops of Asia celebrated Easter on 14th Nisan, the date of the Jewish Passover; bishops in the West, however, celebrated it on the Sunday after Passover.

The difference in practice generated a series of regional councils seeking resolution; these councils agreed with the Western (Roman) position. When the Asian bishops persisted in their practice, which they traced back to the apostle John, Pope Victor I of Rome tried to excommunicate the Asian churches.

Irenaeus and others argued that agreement in faith was compatible with diversity in liturgical practice. They advocated maintaining difference in liturgical practice as long as the understanding of Easter was the same, which it was.

Like other contentious issues, this one would persist as an irritant

and be resolved only by ecumenical councils

in the 4th century.

History of Christianity

The Definitive Emergence of Christianity

• The start of the “history of Christianity” in the proper sense is the middle of the 2nd century. It was then that “Christianity” clearly and definitively emerged from paganism and Judaism as a “third race” (Letter to Diognetus), with a firmer sense of “catholic” identity.

Both the process and product of this emergence would have tremendous consequences for subsequent history.

Christianity is not, first of all, a matter of private experience but of public and communal identity.

Christianity is emphatically material, with a positive view of body, time, and institution.

When facing future challenges to identity, the strategy of Irenaeus would be followed: Bishops would meet in councils and, on the basis of the canonical texts, interpret the meaning of the creed.

Institutional Development before Constantine

History is not merely a matter of great men and the struggle of big ideas. It involves social structures and social dynamics. We have already seen that the 2nd and 3rd centuries were when Christianity became a more definite and visible institution. In this lecture, we’ll focus on the development of such social structures and dynamics during the same period. In particular, we’ll take a closer look at three dimensions of Christianity’s institutional development: its growth in space and numbers, its elaboration of worship and leadership, and its hierarchical structure.

Growth in Territory and Numbers

In the 2nd and 3rd centuries, abundant evidence attests to the expansion of Christianity in terms of territory and numbers.

On the evidence of the extant literature, we know that Christianity extended itself well beyond the places documented in the New Testament.

In Palestine, churches were located both in Galilee and Samaria; after the Roman conquest of Jerusalem, Christian bishops were found in that city, as well.

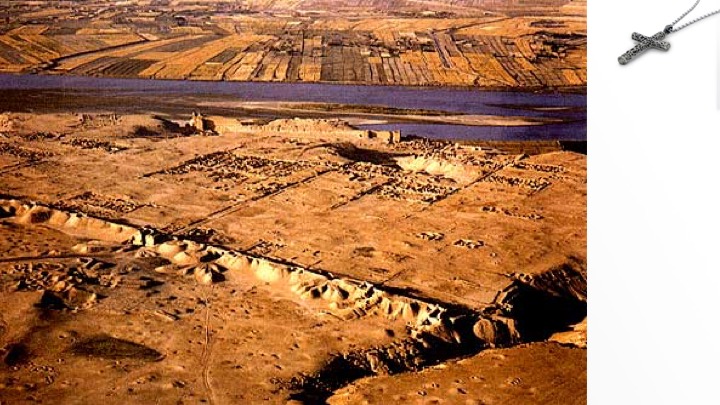

In Syria, Christians moved eastward from Antioch toward Edessa (Osroëne). In the 1930s, an international archaeological team excavated in a Christian house church built before 250 at Dura-Europos on the Euphrates River. Christians also appear east of the Tigris River in Adiabene. Some Syrian Christians made their way to Persia.

More territories in Asia Minor (present-day Turkey)—from the start, an area particularly populous with Christians—added such cities as Nicaea and Byzantium to their numbers.

Excavations at Dura-Europos were first carried out in the 1930s; a house church found there had been destroyed by the Parthians in the year 250.

In Egypt, communities appeared in the metropolis of Alexandria and in the upper Nile. Christianity also appeared in this period in the kingdom of Ethiopia. In North Africa, Carthage and its surrounding areas had a large number of local churches.

In Europe, Christian communities were found throughout Greece, Italy, Sicily, and Spain. There were churches on the Mediterranean islands of Crete and Cyprus. Christians were also attested throughout Gaul, even on the island of Britain.

Other Evidence of Growth

Such expansion across geographical space was accompanied by the production of Christian literature in new languages besides Greek and Latin; compositions in Syriac, Coptic, and Persian appeared in this period.

It is certain that Christianity also grew in numbers, but the data available from antiquity make the determination of numbers mostly a matter of estimate.

Despite the literary portrayal in the apocryphal Acts of the Apostles, there is no real historical evidence of mass conversions based on public preaching or wonder-working.

Growth in numbers more likely came about through a process of social networking. Studies have shown that contemporary cults tend to find converts among those who have family members or friends already in the cult, and that paradigm seems applicable to the nascent Christian movements, as well.

A further factor was simple childbirth. Christians had solid families, and unlike their pagan neighbors, strictly forbade abortion and child exposure; thus, they were successful in multiplying in the most obvious fashion available.

Based on an estimated total population in the Roman Empire of 60 million and a baseline starting population of Christians in the year 40 of about 1,000, by 300, the Christian population was probably more than 6 million.

There are indications, as well, that Christians were finding their way into higher social ranks.

In the years 177–180, the philosopher Celsus, in his attack on Christianity called The True Word, called the movement one of wool workers, cobblers, laborers, slaves, and women.

But in the year 270, Porphyry, another philosophical critic of Christianity, spoke of noblewomen in the Christian religion, and by 300, we see Christians counted among magistrates, provincial governors, and chamberlains in the imperial court.

History of Christianity

Archeological Evidence of Christian Churches

In the 1930s, an international archaeological team excavated a Christian house church built before 250 at Dura-Europos on the Euphrates River.

The house church found there had been partially destroyed by the Parthians in the year 250.

We know it was Christian because of the wall frescoes exhibiting Christian themes, as well as a separate baptistery.

There are abundant examples of Iconography throughout the house church structure (e.g. frescoes of Christ as the Good Shepherd, Christ walking on water, the Samaritan woman at the well, and the myrrh-bearing women at the empty tomb).

Unfortunately, the recent news from Dura-Europa is not good. No archeologists have had access to it since 2011 since the area is under the control of ISIS rebels. But aerial photography indicates there has been major damage and extensive looting to the site.

Let’s look at a few pictures.

This is an aerial view of the

ancient ruins of Dura-Europos. Note the defensive walls around the abandoned city. The main buildings, which included several examples of religious temples, a synagogue, and a Christian house church can be seen on the far side of the town near the Euphrates river.

Two surviving buildings in Dura-Europos.

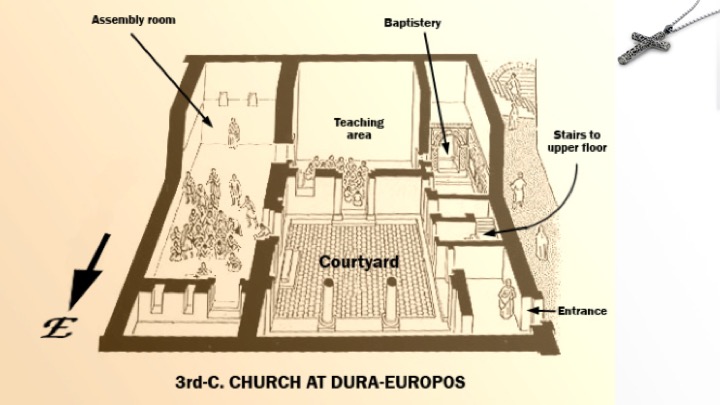

An artists rendering of the layout of the house church. Only the downstairs part of the house is shown. The upstairs was the living quarters of the house church owner.

There were extensive frescos through out the church, such as frescoes of Christ as the Good Shepherd, Christ walking on water, the Samaritan woman at the well, and the myrrh-bearing women at the empty tomb).

The room on the left is assumed to be the worship hall. It could "seat" about 70 people. There was a central courtyard and behind it probably a classroom or meeting room.

At the back right was the baptistry.

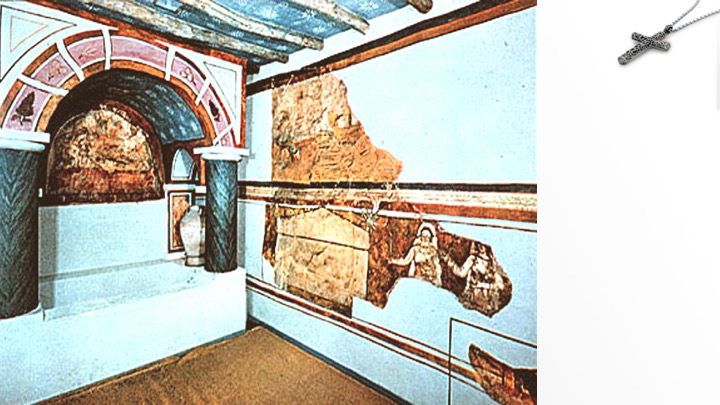

The Baptistery in Dura-Europos

Note – this is not the actual baptistery. This is a re-creation done at Yale University – by the team that excavated the church at Dura-Europos. They noted that the baptistery was very shallow, and only suitable for infants. There was no plumbing so the water had to be poured in. So they are guessing that any adult baptisms were done in the Euphrates river, which was only a short walk away. They only re-created a fraction of the frescos in the baptistry area. This one is believed to be women approaching the tomb of Jesus.

History of Christianity

Growth in Administration

A consequence of this expansion and growth in numbers was the pressing need for greater organization.

A more explicit and elaborate authority structure at the local level was needed to coordinate tasks and administration. Organizing the assembly (its meeting place and times), establishing the order of worship, providing hospitality to delegates from other assemblies, and carrying out other tasks required process and oversight

There was equally a need to conduct communications between and among churches in order to ensure a “catholic” (= “universal”) identity that spanned multiple languages and territories, as letters were sent and received, delegates and missionaries were commissioned and supplied, synods and councils were called and attended, and fellowship was expressed by the sharing of resources.

• Administrative offices at the local level became at once more complex, more centralized, and more infused with religious significance.

In the New Testament, the leadership of local communities appears to be both simple and secular, resembling the basic structure of Greco-Roman associations and synagogues. The New Testament assigns no special religious symbolism to such administration in the local assembly.

A board of elders had a “superintendent” or “supervisor” (episkopos = “bishop”) at its head and lesser functionaries (deacons/deaconesses) to do practical chores.

Paul’s letters indicate that such local leadership was responsible for providing instruction and hospitality, settling disputes, and administering community welfare, particularly the care of orphans and widows.

The letters of Ignatius of Antioch (c. 107) indicate that by the early part of the 2nd century, at least the communities of Syria and Asia had developed a more complex organization with a more elaborate rationalization.

The role of the bishop was now monarchical, and the single authority of the bishop was compared to the singleness of God. The bishop was the source of unity: There was no true Eucharist apart from the bishop.

The elders (“priests”) and deacons were lower orders aligned with the bishops and clearly subordinate. Here, we find the start of a “clerical order” in the proper sense.

A series of compositions of the 2nd and 3rd centuries known as Church Orders devote themselves to the regulation of the common life and show how the roles of the clergy were steadily more developed.

The Didache, or Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, comes from Syria at the end of the 1st or start of the 2nd century. More complex is the Apostolic Tradition attributed to Hippolytus, coming from Rome sometime in the 2nd century. More complex still is the Didascalia Apostolorum, originating in Syria in the 3rd century. Finally, the eight books of the Apostolic Constitutions from the 4th century contain elements of the earlier books.

The authority of the bishop increasingly appeared as supreme within the church, and the bishop was at the center of every activity, especially worship. We can begin to see the language of the Old Testament with respect to sacrifices and high priests now being applied to these Christian leaders and their liturgical activities.

Below the bishop, we find a variety of “lower” clerical orders: acolytes, exorcists, lectors, deacons, deaconesses, priests, and widows. The clergy was responsible for community activities, and its members were sharply contrasted to the laity.

Because our sources take the form of regulations rather than reports of real life, we are left in the dark about many things we would like to know about the ordinary life of Christians in this time. What were those who were not bishops and clergy doing? The sources suggest a vibrant religious life in which the activities of worship and prayer were balanced by a genuine care for the poor and needy within the community.

Local administrative structures were required at least in part because Christians were increasingly in a position to dispose of property, a clear sign that persecution was sporadic rather than steady over these centuries.

After 180, we find the first examples of unmistakable Christian art in the form of biblical themes

on sarcophagi; such sculpting

and accompanying inscriptions indicate a certain

degree of wealth.

Many sarcophagi were discovered by archaeologists in the catacombs, the underground chambers that served as places of burial and were sometimes used by

Christians, especially in Rome, for places of worship.

History of Christianity

Regional Spheres of Influence

The institutional expansion of Christianity in the 2nd and 3rd centuries included the development of regional spheres of influence.

The term “diocese” for the geographical region administered by a bishop (with the help of his clergy) derives—as does the term episkopos, (“bishop”) from Greek political usage: The term was used for economic administration over a geographical area in Hellenistic Egypt.

The bishops of dioceses, in turn, were increasingly coordinated in their efforts by the bishops of major metropolitan sees— also important imperial cities—that were called patriarchates: Alexandria, Antioch, Rome.

As the imperial city par excellence, the church in Rome asserted and exercised the most influence on other regions.

Rome’s authority was far from absolute. As we have already seen, the bishops of Asia resisted the efforts of Victor I of Rome to impose his ruling in the Easter controversy in about 190.

Yet the symbolic and moral authority of the Roman church was real and not only based on the fact of being the imperial capital. Writers at the turn of the 1st century made much of the fact that Rome was doubly blessed in its apostolic founding: Both Peter and Paul were martyred there. Irenaeus, for example, bishop of Lyons in far-off Gaul, made his point about apostolic succession through the bishops of Rome.

In the next century, these centers of regional ecclesial authority would begin to express themselves through theological and political rivalries. With the founding of Constantinople, a real rival to Roman primacy would assert itself.

In terms of sheer numbers, visibility, social standing, and ideological and institutional development, the Christian religion was, by the beginning of the 4th century, no longer an insignificant sect to be dismissed by authorities; it had become a force to be reckoned with by the empire.

< Audio >

Slides used in Class 5