History of Christianity Class 8

A New Radical Christianity - Monasticism

Mike Ervin

History of Christianity Class 8

A New Radical Christianity - Monasticism

Why Monasticism?

An obvious question that might come up in a Protestant Sunday School class. Why are we devoting a full week lesson to something that Protestants do not practice? Our denomination does not have a monastic tradition, nor do we normally get involved with mysticism.

My easy answer answer to that is that this is not a course in Protestantism, we are studying the early development of the Christian church, up until the Reformation, and all of that development was in Western and Eastern Catholic Christianity, which as you will see, has a rich tradition of mysticism and monasticism.

It is important to understand something about the major western Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

These religions are usually thought of in terms of external observance, doctrines, laws, rituals—rather than in terms of intense prayer experiences or forms of contemplation.

In fact, however, all three monotheistic religions of the West have robust and complex mystical traditions. Indeed, those who follow the path of contemplation would argue that their way of being Jewish, Christian, or Muslim was the purest realization of that religion’s essence.

And as you will shortly see that mystic/monastic tradition had a great impact on the development of the church.

For whatever reason, mystics are also responsible for some of the most impressive literature produced by their respective religions. Mystics authored interpretations of Scripture, theological treatises, sermons, meditations, letters, stories, and poems, and all of them testify to the fact that a fervent love of the divine, and a search for contact with the inexpressible, does not require the rejection of literary art or the love of human beauty.

And we will also see that over time many of the leaders of the early church after the establishment of monasteries, often drew leadership (especially Bishops, and occasionally Popes from the monasteries.

History of Christianity

A New Reality

The new conditions of Christianity and Christians within an imperially approved and sponsored religion were not regarded by all Christians as uniformly positive.

With legitimacy and privilege came both security and prosperity at the material level. This meant that Christianity was increasingly “conformed to the world,” rather than its critic, and the bearer of culture, rather than countercultural.

The response of some Christians was the desire to return to what they perceived as a more radical existence. This radical edge—now in reaction to an established imperial church—emerged in the 4th century in diverse forms of flight from society and asceticism that are gathered under the term “monasticism.”

The Turn to Monasticism

The desire for a more radical existence among some Christians was continuous with elements in the New Testament that exhorted believers “not to be conformed to this age” (Rom. 12:2), and to “go outside the camp” to suffer as Jesus did outside the city, “for here we have no lasting city” (Heb. 13:13). Likewise, some Christians looked back at the portrayal of the first believers as sharing all their possessions and having nothing they called their own (Acts 2:41– 47, 4:32–37).

The desire was continuous, as well, with those elements of radical Christianity that persisted through the age of persecution: the boldness of those facing martyrdom, who chose Christ rather than Caesar; the representation of the apostles as subverters of the social order, who challenged the stability of both household and state; the New Prophecy that looked to a heavenly Jerusalem; the forms of Gnosticism that rejected all outward forms to cultivate the spirit.

Some precedent for “living apart” in community had been set already by certain Greco-Roman philosophical schools. The Epicureans and the Pythagoreans had a long history of “life together” outside the bounds of ordinary society. The Pythagoreans, indeed, maintained a regimen of silence, were vegetarian, and shared their possessions in common.

Precedents can be found also in Judaism—probably influenced by Greco-Roman models: The Essenes and Therapetuae described by Philo of Alexandria and the community life at Qumran revealed by the Dead Sea Scrolls indicate that some pious Jews also sought a more rigorous form of observance away from the distractions of society. The most authentic expression of Judaism in such practitioners’ view was through total dedication, away from possessions, family, and social entanglement.

History of Christianity

The Spirituality of the Desert

The future direction of Christian Mysticism was not set by Gnosticism, although versions of it continued to occur on the margins, but by a thoroughly orthodox form of spirituality that arose and thrived in the 4th-century Egyptian wilderness.

A. Unlike the Gnostics, who craved the speculation found in revelatory writings while scorning the Old Testament, the desert monks embraced all of canonical Scripture, finding meaning especially in the Psalms.

B. Unlike the Gnostics, who regarded Christ primarily as the revealer of truths concerning their own inner light, these ascetics modeled themselves on the Jesus of the Gospels, especially in his suffering.

C. Unlike the Gnostics, whose mysticism consisted, above all, in theosophy (knowledge of the divine), the desert fathers and mothers sought the moral transformation of their lives, desiring sanctity.

D. Unlike the Gnostics, whose self-realization was instantaneous and total, desert spirituality emphasized a slow process of moral discipline and constant prayer.

The Beginnings

Antony of Egypt

The symbolic if not necessarily factual start of the solitary wilderness life (eremitical life) is Antony of Egypt (c. 251–356).

Our knowledge of Antony comes from the Life written by Athanasius of Alexandria, around 360, shortly after the death of the hermit. It was written in praise and to provide a model to others; the biography had wide influence.

While still a young man (c. 269), Antony heard the Gospel passage in which Jesus tells the rich young man, “Go, sell all your possessions and come follow me” (Mark 10:21). Antony took these words literally, left his goods to his sister, and went to the Egyptian desert.

Anthony made successive withdrawals (in the years 285 and 310) deeper into the wilderness, as Antony’s desire to be alone (monos) is thwarted by the desire of disciples to join him. Antony’s ideal was the solitary life of the hermit (eremos = “wilderness, desert”).

Already in this account, we glimpse some of the elements of the early monastic life.

The world is perceived as corrupting; the desire to be alone and apart is the desire to achieve true discipleship through struggle.

Just as martyrdom was earlier associated with “fighting demons,” that is, the heathen gods and the state that sponsored them, so now the monk “fights the wild beasts,” who are inner demons in the fight for authentic faith. Thus, monasticism is a form of “white martyrdom.”

The arena for battle is the human mind and body. The control of the body through mental dedication (asceticism) is a key dimension of early monasticism, sometimes taking extreme forms, such as severe fasting and lack of sleep.

In contrast to the Gnostics, these early monks were deeply dedicated to ecclesiastical authority and orthodoxy—at least, this is the portrayal given by Athanasius, the bishop of Alexandria.

The “sages of the desert” were charismatic in the sociological sense of the term: They drew followers who sought the wisdom they personified.

History of Christianity

Types of Monasticism in Egypt

Three main types of monasticism developed in Egypt around the Desert Fathers and Mothers. One was the austere life of the hermit, as practiced by Anthony and his followers in lower Egypt.

Another was the cenobitic life, communities of monks and nuns in upper Egypt formed by Pachomius.

The third was a semi-hermitic lifestyle seen mostly in Nitria, Kelliaand Scetis, west of the Nile, begun by Saint Amun. The latter were small groups (two to six) of monks and nuns with a common spiritual elder—these separate groups would join together in larger gatherings to worship on Saturdays and Sundays. This third form of monasticism was responsible for most of the sayings that were compiled as the Apophthegmata Patrum (Sayings of the Desert Fathers).

Cenobites

Another form of the monastic life was that of “life together” in the wilderness. The term “cenobite” for such monks comes from the Greek koinos bios (“life together”).

The founder of this form of monasticism in Egypt was Pachomius (290–346).

Born a pagan, he served as a Roman soldier and was converted in 313.

He founded a monastery (c. 320) at Tabennisi in the Thebaid near the Nile.

By the time of his death, he had under his authority some nine monasteries for men and two for women, with thousands of members.

The Pachomian Rule regulated for many monks living “the solitary life” in common, in a rhythm of isolation and community.

Time alone was spent in prayer and meditation and in the working of small crafts.

Time together was devoted to meals, common prayer, and instruction.

The Pachomian form of monasticism would be amplified and altered by others in the East (Basil of Caesarea) and in the West (Benedict of Nursia). But Pachomius established the dominant pattern of Christian monastic life.

History of Christianity

John Cassian

An important source of knowledge about monastic ideals is John Cassian (360–430). His two books, Institutes and Conferences are compendiums of monastic lore from Egypt.

From Scythia (the territory around modern Russia and Ukraine), Cassian learned from the early monks in Egypt (c. 385), spent time in Constantinople, and in 415, founded two monasteries in Marseilles, where he composed his two great works.

The Institutes elaborates the cenobitic life in great detail, including manner of dress, work, and prayer.

The Conferences takes the form of sermons given by the desert monks on topics extending from prayer and contemplation to fighting the “noon-day devil” (accidie, or boredom).

The Ongoing Movement to the Desert

So popular was the wilderness life that a virtual “city in the wilderness” appeared in the Egyptian desert, with monasteries for both men and women scattered everywhere.

The monks presented an alternative culture, based not on wealth but poverty, not on power but weakness, not on prestige but lowliness.

In their communal life, they saw themselves as “New Testament Christians” living the “apostolic life” described by the Acts of the Apostles.

In a real sense, the impulse that drove the Reformation of the 16th century was active already in early monasticism: a return to simplicity, poverty, the imitation of Jesus, and the trusting faith of the heart.

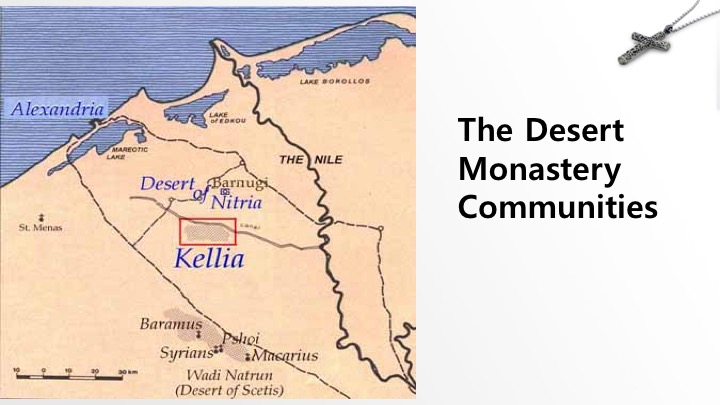

Let's look at a slide map of the desert areas in Egypt where the Desert Mothers and Fathers congregated.

Map of the Desert Communities

The Primary Monastery Communities of the 4th and 5th centuries were consecrated in three areas. The desert of Nitria was the starting point, and had many of the “hermits”, the solitary ones.

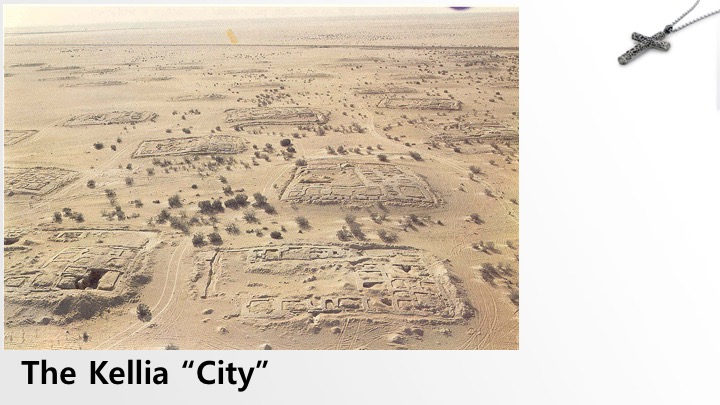

The Cenobitic communities established what some called “cities in the desert” in the area called Kellia. We will probably never know how many. But some have estimated that Kellia at one time had 70,000 monks. Others have said no – it was more like 20,000.

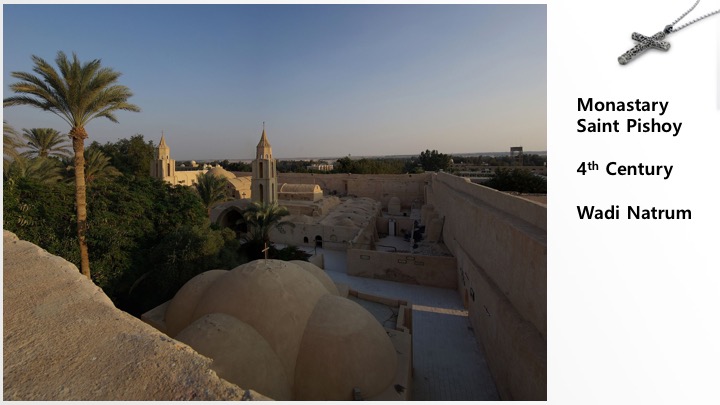

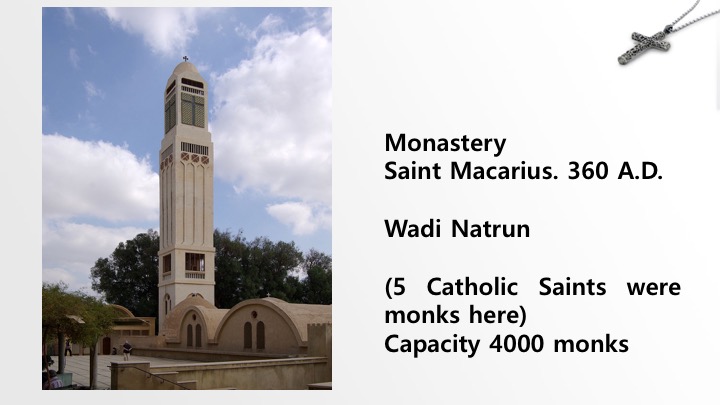

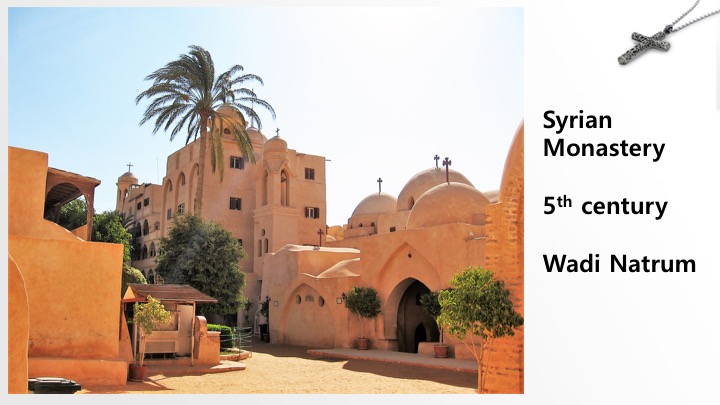

The last big area was the Desert of Scetis. In particular the area known as Wadi Natrun is today the location of many very impressive monasteries that are still in active use today. We will look at some pictures of them later.

Slide Picture - note from the slides the picture of the Kellia City from the air today. The remaining structures of the many small monasteries stretch out of sight in all directions. It appears that each small building would hold about 15 or so monks.

History of Christianity

The Participation of the Wealthy and Sophisticated

Evagrius of Pontus (345–399) was born Christian and was educated in Constantinople. After an inappropriate love relationship when in priestly orders, he fled to Jerusalem and joined a monastery of Rufinus and Melania. He spent most of his life in the desert in Nitria. A disciple of Origen, his writings (the Praktikos and the Gnostic Chapters) had a great influence on later spirituality.

Palladius (c. 364–420/30) was born in Galatia. As a young man, he traveled extensively in Egypt among the monks, collecting stories in the manner of an ethnographer. He later became bishop of Heliopolis in Bithynia. In his Lausiac History, he presents a vivid picture of the cultural complexity represented by Egyptian monasticism.

Palladius is an example of a well-established figure in society who “goes on pilgrimage” to visit the monks of Egypt and Palestine, collecting stories and sayings and seeking a simplicity and nobility of life not available in the cities.

Among the notable figures on whom Palladius reports are wealthy patronesses, such as Macrina, a Roman matron who used her massive fortune to establish and support monastic foundations and meet the practical needs of the monks. Here, we see the practice of patronage in yet another form.

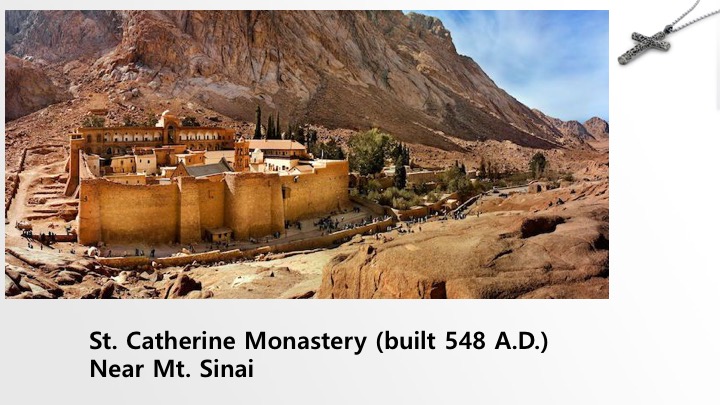

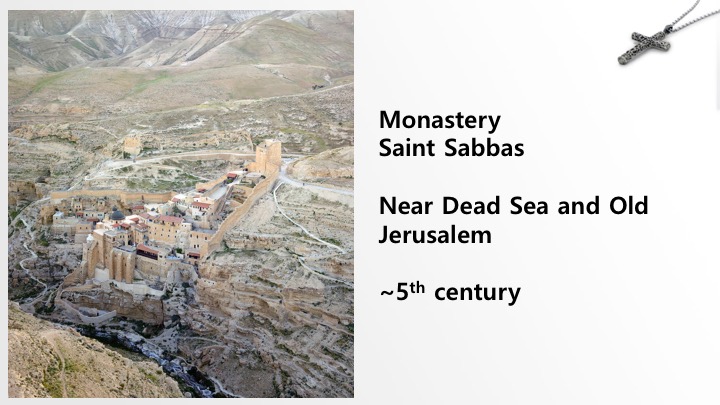

Turning to the slide pictures. We will quickly look at 5 beautiful monasteries, several in the Wadi Natrum area I pointed out before. All of these were constructed initially in the 4th and 5th centuries and are still active monasteries today. i do not know their histories, perhaps like many ancient buildings they have been rebuilt multiple times due to destructions form invaders, or other catastrophes.

The Monastery Saint Macarius is notable for having many monks thru the centuries that became saints of the church, as well as many who became Bishops.

The Saint Catherine Monastery at the base of Mount Sinai is still active and claims to have the longest continually operating library in the world. The Codex Sinaiticus, a famous very early copy of the Septuagint, was discovered here and has been a treasure to biblical scholars involved in textual research of the Bible. It is now housed in several places, mostly in the British Museum.

Summary – the Influence of Monasticism

Monasticism found a permanent place within Christianity and exercised enormous influence from the first.

Many bishops of the 4th to 6th centuries were drawn from monastic ranks and were, thus, leaders who were ascetical, celibate, and often scholarly, shaped by the discipline and sharing the outlook of monastic life.

Monks served as “foot soldiers” in the fierce doctrinal wars of these centuries. They were the most activist, mobile, and militant Christians; it was not unknown for them to riot in patriarchal cities in support of one doctrine or another.

The role of monasticism in the long run was equally important.

Through the ages, monasteries provided a constant “alternative lifestyle” that enabled Christians to express their discipleship in more radical fashion. They were an outlet for those with reforming impulses, and while not always approved by more enculturated Christians, they were always admired.

At some times and places, monasteries provided centers for reform through knowledge and practice. In the early medieval period of the West, monasteries preserved and copied manuscripts and taught the techniques of agriculture.

And Next Week - we will explore the further Expansion of Christianity, not only that Christianity near the core of the Empire, but on the fringes and completely outside. Then we will briefly review the Emergence and Rise of Islam.

< Audio of Class >

Slides - Class 8 - Christian Monasticism