History of Christianity - Class 9 -

Further Expansion and the Rise of Islam

History of Christianity - Class 9

Further Expansion and the Rise of Islam

We are now on Lesson 9.

Christian Expansion Beyond the Boundaries of Empire

There has been a common tendency by some to think of Christianity as a European religion or its appearance in other lands as the result of European imperialism. As we will see, the truth is far different.

One reason think this is that the literature and material culture within the empire are more abundant, accessible, and appealing. For example, the German tribes left little evidence of their rapid spread across Europe, and while the architectural remains in Ethiopia are of great interest, they are sparse in comparison to those of the empire.

Another reason is that the forms of Christianity outside the empire quickly became “heretical” in one form or another and, thus, drifted away from “authorized” versions of the Christian story. It is an easily understandable temptation for the historian to tell the story of those who are our direct forebears.

Yet another reason is that the languages that tell their stories are known by relatively fewer professional scholars. Much of the substantial literature in these languages, especially in Syria and Egypt, remains untranslated and, therefore, unknown to generalists.

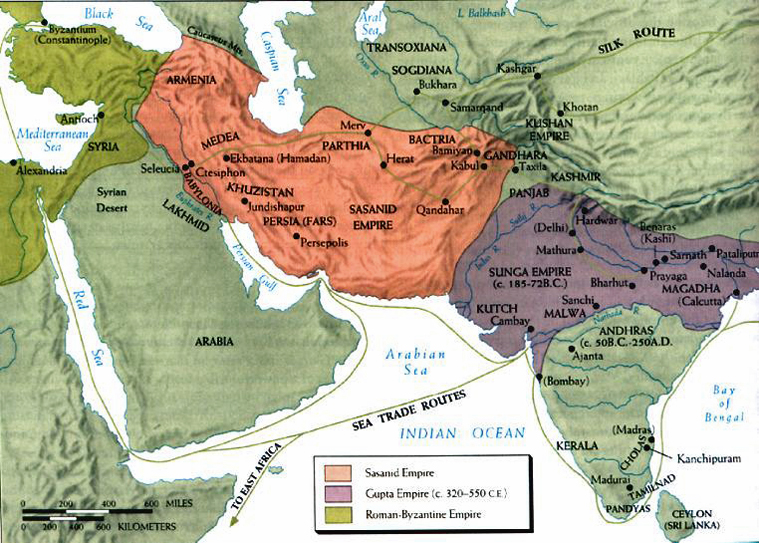

Expansion of Christianity in the East

The expansion of Christianity in the East began early, was inevitably caught up in the doctrinal disputes within the empire, and through translations of the Bible into new languages, spread both a Christian consciousness and a sense of cultural identity.

In both Syria and Egypt, Christianity quickly expanded beyond the Hellenistic cities of Antioch and Alexandria.

By the 2nd century, Christianity flourished around Edessa in East Syria. Early translations of the Old and New Testaments were in the form of Syriac (a dialect of Aramaic); a complete translation of the Bible (the Peshitta) was completed by the end of the 4th century. A great ecclesiastical literature also was generated in Syriac.

Similarly, in upper Egypt, evidence of Christianity in the Coptic language appears from the 3rd century, with the New Testament appearing in several Coptic dialects and Gnostic writings, such as those found at Nag Hammadi, composed in Coptic.

In Persia, Christianity made an appearance in the 3rd century and continued to flourish through some vicissitudes. Under the Sassanid king Shapur II (310–380), Christians underwent a 40-year persecution; the ecclesiastical historian Sozomen reports that 16,000 were killed.

From 399 to 420, in contrast, Christians enjoyed royal favor. The Bible was read in Syriac, but some efforts were made to translate it into Middle Persian. From 420 to 450, there was again persecution.

As we have already seen, the kingdom of Armenia became the first official Christian state in the beginning of the 4th century, when Gregory the Illuminator converted King Tiridates III. In the 5th century, Saint Mesrob established a school of Christian literature; in 433, an Armenian translation of the Bible based on the Greek was produced. A substantial Christian Armenian literature followed.

In the 4th century, Constantius

II (the imperial sponsor of Arianism) sent Bishop Theophilus

to the Sabaean

tribal people in Yemen. An Arabic translation of the New Testament appeared

there in the 7th

century. But Christianity in Yemen was overrun by Islam, and the remaining

Christians were Nestorian in their outlook.

Persia became the center of Nestorian Christianity, which emphasized the humanity rather than the divinity of Christ. Nestorianism eventually became the national church and the source of missionary activity along the trade routes to the Far East.

Further Expansion of Christianity in the East

The Armenian church became monophysite in its doctrine, emphasizing the divinity of Christ and downplaying his humanity. From the 6th century on, the Armenian church developed separately from the church of the empire.

Christianity appeared in Ethiopia (Abyssinia) in the middle of the 4th century, where it quickly became deeply entrenched, independent, and idiosyncratic. Mixed with Jewish and Islamic elements, Ethiopian Christianity survives, and thrives, to the present.

Two men, Frumentius and Edesius, were sold as slaves from India to the court at Axum and converted King Ezana. The Ethiopians refused Constantius’s offer to convert to Arianism. Instead, under the influence of the church in Alexandria, Ethiopian Christianity became decidedly monophysite.

In the 5th or 6th century, a translation of the Bible into Ethiopic was carried out. And in the 6th century, evangelization took place among the Nubians (north Ethiopia) and the Nabataeans; a Nubian translation of the Bible dates from the 8th century.

So, despite the belief of some that Christianity would not have spread without the Roman empire, in fact, outside of the immediate core of the empire, Christianity continued the high growth seen earlier in the first three centuries

Now - let's turn to the West.

Expansion of Christianity in the West

In the West, Christianity found adherents among the Germanic peoples as they were sweeping around and through the western part of the empire.

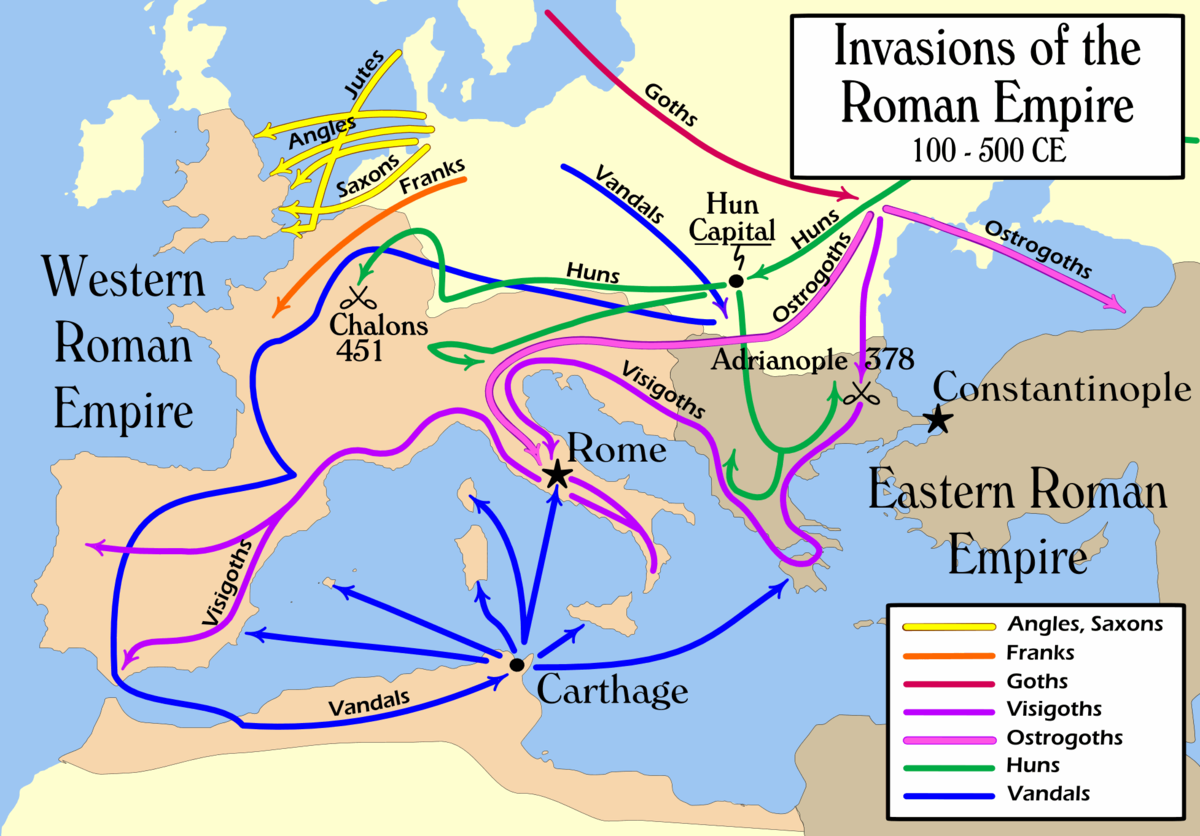

The context of Christianity’s encounter with these tribes is the great migration of peoples that occurred over a period of several hundred years in a broad movement westward and southward, even into Africa. It is impossible to neatly sort out everything that happened because movements were simultaneous and overlapping, but we can make three framing comments.

(1) Relations with the empire among the tribes varied from neutral to hostile to positive. By no means is it appropriate to think solely in terms of an invasion or conquest of the empire, although battles and victories were sometimes involved. More adequate is to think in terms of the Roman administration incapable of handling the floods of people who wanted some part in Rome.

(2) Overall, the Germanic peoples demonstrated a strong tribal structure, with value given to loyalty and honesty, and a native pagan religion that was open to the supernatural. Clearly, some form of Christianity held a strong attraction for them.

(3) Because of their rapid geographical movement, the Germanic peoples left behind little monumental or literary evidence of their Christian commitment. It was through Christianity that literacy came to these tribes.

We can review, briefly and inadequately, the traces of five groups of tribes, whose presence placed extraordinary pressure on the western empire, finally overwhelming it completely.

Lets first take a look at 400 years of migration of the German tribes into the Western Roman empire.

And by 526 of the common era we see that there is no longer a westrn Roman empire. The Germans are in control. There is still an eastern Roman empire, headquartered in Constantinople, but it is a diminished empire in size, having lost the west and a substantial part of what they had earlier conquered in the east.

In Summary

The Visigoths (western Goths) moved from the northern shore of the Black Sea along the Danube all the way to Spain. They were evangelized by Ulfilas for almost 40 years (345–383) under the direction of the Arian emperor Constantius

He was a Greek-speaking Cappadocian who learned the Gothic language, devised an alphabet for the language, and then translated the Bible into the “Gothic version,” of which is extant the so-called Codex Argentum (Silver Codex).

The Visigoths located first in Thrace, then moved through Greece and Italy, and ended in southern Gaul and Spain (c. 419), where they mixed with the local populations.

They remained Arian in their understanding of Christianity until the 7th century, regarding Christ as not fully divine.

The Ostrogoths (eastern Goths), another German tribe, started in Pannonia—an area encompassing modern Poland—and migrated to Italy in 489, establishing an extensive and stable kingdom under Theodoric the Great (471–526).

The Ostrogothic kingdom lasted for some 60 years, until 553, and included Italy, Sicily, Dalmatia, Pannonia, and Provence— with ambitions to annex the Franks.

The Ostrogoths were also Arian and repressed Catholic Christians, imprisoning the philosopher Boethius (in 524–525) and Pope John I (526).

The tribe called the Lombards also started in Pannonia, leaving there in 586 and conquering most of Italy, with the exception only of Ravenna, Rome, and part of the south.

The Lombards were mostly Arian and hostile to Catholics.

Eventually, they became Catholic, and the Lombard and Roman populations merged.

The most aggressive tribe, the Vandals, started in Pannonia, devastated Gaul in 409, settled in Spain for a time, then crossed over to North Africa (429).

Under King Genseric (428–477), Roman power in North Africa was crushed, and a stable Vandal kingdom was established, lasting almost a century, until the reconquest of North Africa by the emperor Justinian in 524.

The Vandals also were Arian and intensely hostile to Catholics.

Finally, the Germanic people called the Franks would eventually become the most dominant in Europe. They came from the lower Rhine in the middle of the 5th century. Their king, Clovis I (481– 511), ended Roman rule in Gaul in 486 and conquered all of middle Europe. Clovis converted to Catholicism in 496, and Catholicism thrived in the Frankish kingdom. It was through Frankish rule, as we shall see, that Europe eventually adopted the Catholic rather than the Arian form of Christianity.

Expansion of Christianity in the North

Britain was conquered by the Romans in the 1st century. The island was evangelized as early as the 2nd century but remained significantly pagan until the 6th century, when the Pope sent 50 Benedictine monks to Britain and finally established relations .

Rome never invaded Ireland, which became Catholic through the missionary work of Saint Patrick in the 5th century.

Similarly, Southern Scotland and Northern Scotland were converted to Orthodox Christianity through the dedicated work of individual missionaries.

Conclusions About the Expansion

Although the Roman Empire had attractions, Christianity succeeded in many places despite imperial power rather than because of it. This religion, in whatever form it appeared, clearly had the capacity to attract people on its own terms.

This survey confirms the point made earlier that what is called “orthodox” Christianity is, to a large extent, to be identified with imperial Christianity, while outside the empire, Christianity was most often Arian, Nestorian, or monophysite.

The powerful movement of peoples in the West and the evangelization of those tribal peoples would form the future cultural context for the Latin church.

And now, let's breifly review our second important subject of today. The rise of Islam.

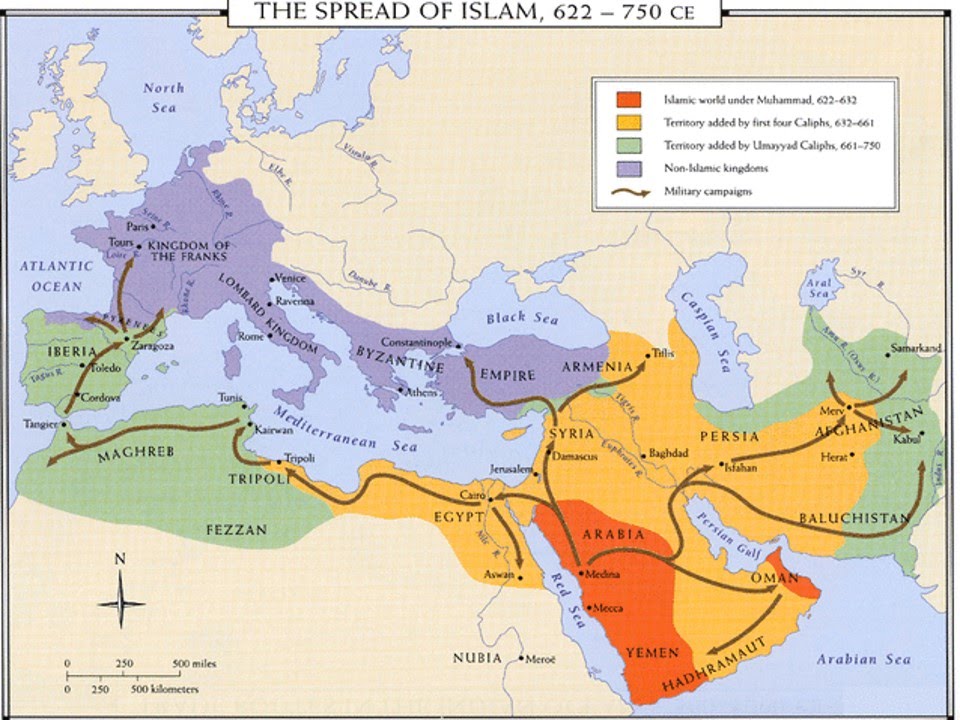

The Spread of Islam

The prophet Muhammad was born in 570 C.E., had his initial vision in 610, fled to Medina in 622, and died in 632.

From the time of his first vision, the prophet recited aloud in Arabic the words he received by dictation from Allah; these words, organized into suras (“chapters”), were posthumously gathered into the Qur’ān.

The Qur’ān provides a vision for the ordering of society, with legislation concerning every aspect of life; subsequent generations developed its statements and the hadith (example) of the prophet into a system of law (shariah) governing an Islamic state.

In 633, they attacked Persia. In the same year, the churches of Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria were lost to Christianity because of Islamic conquest.

Between 634 and 637, Syria, Persia, Egypt, and Gaza were conquered. In 639, the kingdom of Armenia was attacked and, in 694, defeated.

Under this onslaught, Persia sought the aid of China in 638, but by 641, it fell to the Arab army. Once the East was secured, the Arab forces turned westward. In rapid order, Arab armies conquered Tripoli, Cyprus, North Africa, Carthage, Algeria, and Spain.

In 655, the Arab navies defeated the Byzantine fleet, and in 693, the Arab army defeated the Byzantine army at Sebastopolis in Cilicia.

In 655, the Arab navies defeated the Byzantine fleet, and in 693, the Arab army defeated the Byzantine army at Sebastopolis in Cilicia.

By 715, Islam extended from the Pyrenees to China, and its ambitions did not stop there; its eyes were on the complete subordination of Europe to the rule of Allah. In 716, Lisbon was conquered by Muslim troops, and in 720, the Muslim army reached France (Narbonne).

In the West, only Charles Martel (The Hammer), leader of the Franks and grandfather of Charlemagne, was able to stop the Muslim progress at the Battle of Tours (or Poitiers) in 732. He did more than just stop them, it was a rout. The Muslim armies were totally defeated and far from home. They decided to give up their plan to attack Europe from the west.

Constantinople proved to be a more difficult task. But the aggressive religious and political threat of Islam hovered at the edge of the Byzantine Empire until the eventual collapse of Constantinople in 1453.

The Roman Empire was no more at that point (1453). But we should now return to the eight century to resume our story on the development of Christianity.

Next Week

We have pretty much wrapped up Phase II of our grand exploration and now will set the stage for Phase III. Our first class will be class 10:

"From the Roman Empire to the Holy Roman Empire in the West"

< Audio of Class 9 >