History of the Bible Lesson 12

Translations into the People's Languages

History of the Bible Lesson 12

Translations into the People's Languages

The Story of the Bible so far has not lacked drama. But it is about to get more dramatic.

If the Renaissance and the printing press gave Europe a new appreciation of the past, a thirst for change, and a broader understanding of what was in the Bible, the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century used the Bible to challenge the medieval Catholic understanding by a deeper appeal to the past and in doing so changed the world. In fact it created a new Europe.

A Brief Review

The Medieval Period was a golden age for the Bible and a period of remarkable ecclesiastical unity for the Church.

The Renaissance began a questioning attitude toward the medieval synthesis – there were great and perhaps superior philosophical systems that predated Christianity.

The printing press rather suddenly made both the Bible and other philosophical systems available to a wider audience.

And the Reformation then created unimaginable changes in Europe and the world.

Overview of Today

Ø The Reformation shattered the religious and cultural unity of medieval Europe and helped fragment political unity;

Ø Christendom broke into separate states defined, in part, by their allegiance either to the Catholic or some Protestant version of Christianity and, in part, by distinct national identity.

Ø The translation of the Bible into the separate European languages was part of this process.

We will review early efforts to make the Bible accessible to populations in their own languages and review the contents of the Bible for the distinct communities of faith.

There Was Not Just One Reformation

Reformations

Ø Lutheran

Ø Calvinist

Ø Anglican

Ø Anabaptist

Catholic Counter Reformation

Ø Council of Trent (1546)

Ø Some Moral Reform

Ø Education of the Clergy

Ø A Vigorous Attack on Protestantism on all Fronts.

It is of note that the Peace of Westphalia, which was a formal legal (and binding) document, clearly spelled out that Protestantism was legal and here to stay, explicitly stated that only three forms of Protestantism were allowed when the "Prince" choose his religion. Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican. The Anabaptists were excluded. Probably one of the reasons why there was an eventual mass migration of Anabaptists to the Americas (and a few other places) because unlike Europe the Americas offered something much closer to the idea of religious freedom. Europe had freedom of religion only for the Prince or King.

A Loss of Social and Religious Unity

The Constantinian premise of the unity of state and Church continued.

But increasingly in the direction of Erastianism-the supremacy of state over Church.

The basic premise of the Peace of Westphalia was captured by the latin phrase:

“Cuius regia eius religia”

("the religion of the prince is the religion of the realm")

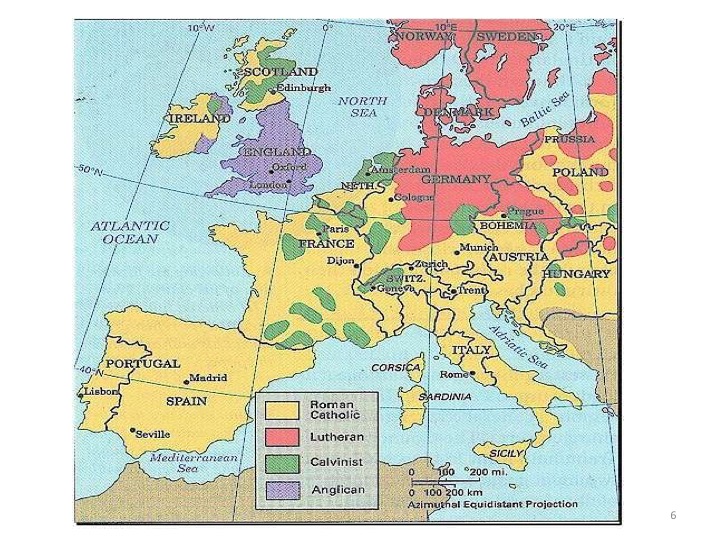

As a result Europe became a checkerboard of Protestant and Catholic countries, with Catholicism in France, Italy, and Spain and one form of Protestantism or another in Germany, Scandinavia, England, and part of the Low Countries.

The Religious Checkerboard

This map was the result of cuius regia eius religia. The yellow represents Catholic lands, the red Lutheran lands, the purple Anglican, and the patches of green Calvinism.

A Loss of Social and Religious Unity

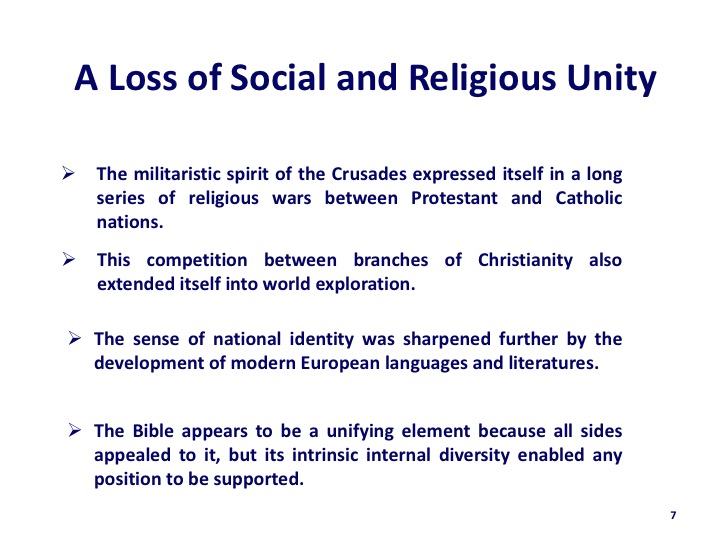

The militaristic spirit of the Crusades expressed itself in a long series of religious wars between Protestant and Catholic nations.

This competition between branches of Christianity also extended itself into world exploration.

The sense of national identity was sharpened further by the development of modern European languages and literatures.

The Bible appears to be a unifying element because all sides appealed to it, but its intrinsic internal diversity enabled any position to be supported.

A Brief and Simplistic Review of the Indo-European Language Groups

Before we move into a review of the many translations that began to appear it might be useful to review in one slide what the Indo-European language groups entailed. According to linguists today about 94 % of the people of Europe fall into three prominent language groups as follows:

Romance Languages

Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, Romanian, Sicilian, Catalan, Gallaecian, Sardinian, & others.

Slavic Languages

Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Polish, Czech, Slovak, Sorbian, Serbo-Croatian, Slovene, Bulgarian, Macedonian & others.

Germanic Languages

German, English, Dutch, Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, & others.

So, when thinking of translating into the people's languages, it is evident that this is a formidable task, as there are many.

And There is More Than One Bible

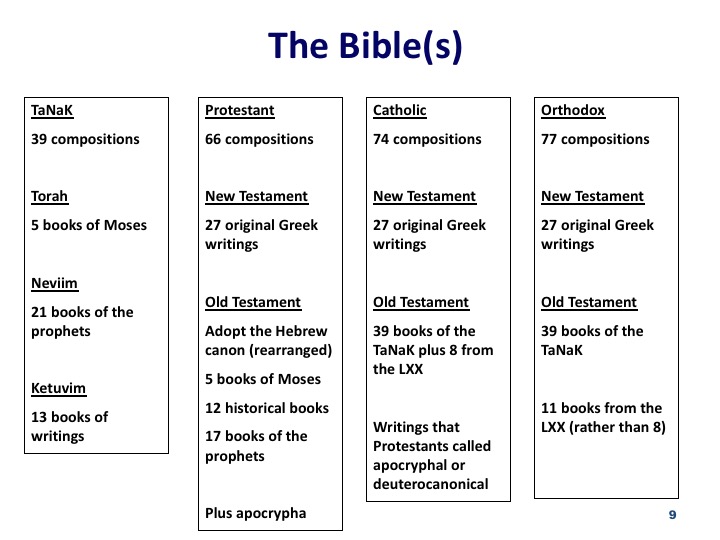

The TaNaK (Hebrew Bible, has 29 compositions, the 5 books of Moses, 21 books of the prophets, and 13 books of the writings.

The Protestant has more, 66 compositions, including 27 books of the New Testament. And the Protestants adopted the Hebrew canon (in a rearranged form) with the 5 books of Moses, 12 historical books, and 17 books of the prophets.

Many Protestant Bibles sometimes included the apocrypha, not as part of the canon, but as supplemental reading.

Catholic Bibles had 74 compositions, the same 27 books of the New Testament, the same 39 from the TaNaK, plus 8 books from the Septuagint (LXX). All are part of the Catholic canon.

And finally, the Eastern Orthodox Bible had 77 compositions by including 11 books form the LXX.

So translating the Bible was an even more complex process because there were so many different Bibles. Still, Bible translations began occurring all over Europe, both before and during the Reformation Era of 1500-1650 C.E.

Becoming The People’s Book

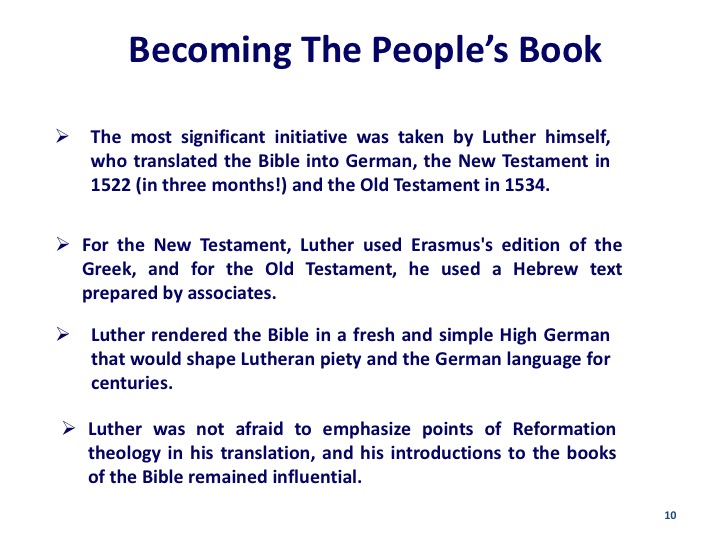

The most significant initiative was taken by Luther himself, who translated the Bible into German, the New Testament in 1522 (in three months!) and the Old Testament in 1534.

For the New Testament, Luther used Erasmus's edition of the Greek, and for the Old Testament, he used a Hebrew text prepared by associates.

Luther rendered the Bible in a fresh and simple High German that would shape Lutheran piety and the German language for centuries.

Luther was not afraid to emphasize points of Reformation theology in his translation, and his introductions to the books of the Bible remained influential.

Phillip Schaff –History of the Christian Church wrote of Luther's achievement:

"He made the Bible the people’s book in church, school, and house. If he had done nothing else, he would be one of the greatest benefactors of the German-speaking race.

In the German tongue he had no rival. He created, as it were, or gave shape and form to the modern High German. He combined the official language of the government with that of the common people. He listened, as he says, to the speech of the mother at home, the children in the street, the men and women in the market, the butcher and various tradesmen in their shops, and, "looked them on the mouth," in pursuit of the most intelligible terms. His genius for poetry and music enabled him to reproduce the rhythm and melody, the parallelism and symmetry, of Hebrew poetry and prose. His crowning qualification was his intuitive insight and spiritual sympathy with the contents of the Bible."

Other Languages

Spanish - The first complete Bible from the original languages was the Biblia del Oso by Casiodoro de Reina in 1569.

French - The Port-Royal version by Antoine and Louis Isaac Lemaistre in 1695 won wide acceptance by both Catholics and French Huguenots.

In the Netherlands, the first translation into Dutch from the Hebrew and Greek was ordered by the Synod of Dordrecht (1618) and appeared in 1637.

Gustav I Vasa (1496~1560) converted Sweden to Protestantism and ordered the Bible to be translated into Swedish.

Other Languages

Among both Protestants and Catholics, translations into other European languages cemented national identity and helped shape national literatures.

The Bible was translated from the Vulgate into Czech in 1488, then from the original languages between 1579 and 1593.

The New Testament was translated into Finnish in 1548, and the whole Bible appeared in 1642.

In Hungarian, the New Testament was printed in 1541, and the entire Bible in 1590

A Polish translation of the Bible came out between 1541 and 1597.

Englishing the Bible – Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (1325-1384) translated the Bible from Latin into English because of his conviction that it should be available to all. He was a reformer well ahead of his time.

He was an Oxford don who studied philosophy and was outspoken in his criticism of the Church. He advocated that the civil governments should have authority over the church, and was a strong critic of the cult of the saints, the sacraments, transubstantiation, monasticism, and the existence of the Papacy.

The Wycliffe translation (1382) was extremely literal, handwritten, and based on the Vulgate. To us it would have been unreadable, written in Middle English.

Wycliffe was condemned by the Church of England. But never severely punished. Although it did not have wide distribution (this was well before the printing press) Wycliffe's English Bible did became popular in England, even among Catholics. There are still 250 copies of it in libraries and museums.

Footnote – Wycliff died of natural causes, and as we said was never excommunicated or executed for his views. But about thirty years later, the Council of Constance of the Catholic Church achieved revenge against Wycliff by condemning his teachings and ordering his bones to be dug up and burned.

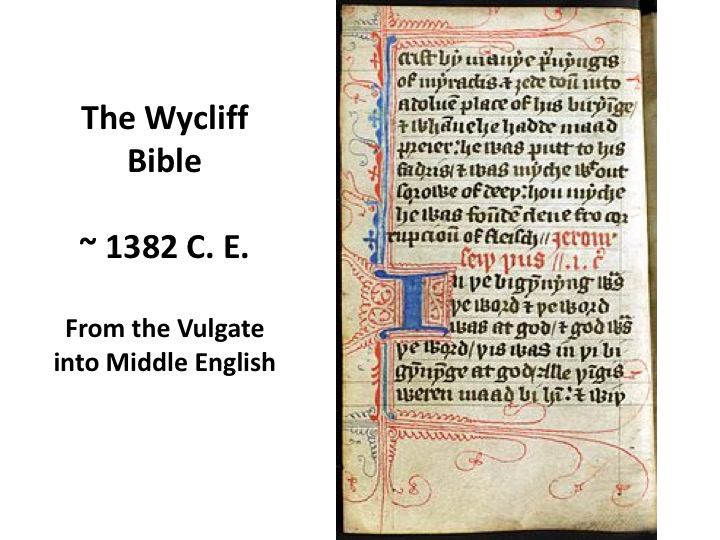

This is one of the surviving copies of the Wycliff bible. Handwritten, but of apparently high quality, and beautifully illustrated. This is the opening page of Genesis - the top part of the page is a kind of preface and Genesis 1:verses 1-2 below that. Although the middle English is close to unreadable to modern English readers - you might be able to tell that the first three words are "In the beginning".

William Tyndale (1494-1536)

We now come to one of the great translators involved in Englishing the Bible. William Tyndale (c. 1494-1536), whose work laid the foundation for all that followed.

Tyndale studied at Oxford, then Cambridge, from 1510 to 1515; a skilled linguist, he was skilled in ancient Hebrew, ancient Greek, Latin, Spanish, French, Italian, German, and English. Ridiculous.

He wanted to translate the Bible in 1522, but the bishop of London refused permission (Luther's works were burned at St. Paul's in 1521); thus, in 1524, Tyndale moved to Germany.

He worked directly from the Hebrew and Greek. The printing of the first edition of the New Testament was in 1525, and it was attacked in England in 1526. He printed his translation of the Pentateuch and Psalms in 1530 and of Jonah in 1531. At his death, Job through 2 Chronicles was in manuscript.

In 1535, agents of the English King tracked him down, and he was arrested near Brussels, imprisoned for almost a year, then strangled, and burned at the stake. Such is the fate of anyone who dared to translate the Bible into the people's language.

At his execution Tyndale prayed, "Lord, open the King of England's eyes."

The prayer was answered, but two years too late for Tyndale. In 1537, Henry VIII allowed the English Bible to be distributed in his kingdom.

Tyndale’s Legacy

It is Tyndale who fashioned the idiom of "biblical English”. His influence has been as wide as Shakespeare's.

- "let there be light," (Genesis 1)

- "the powers that be," (Romans 13)

- ”a law into themselves," (Romans 2)

- ”fight the good fight," (1 Timothy 6)

- "my brother’s keeper," (Genesis 4)

- "the salt of the earth," (Matthew 5)

- ”filthy lucre," (1 Timothy 3)

- ”the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak," (Matthew 26:41)

We use these phrases because they are well formed. Their alliteration, rhyme and word repetitions say what we need to say, with the force we need, so even those who never read the Bible still use them.

And almost all of them were was taken up by subsequent translations, including the King James Version.

His phrases are so well-known that they are often thought to be proverbial.

Tyndale’s Legacy

Tyndale had a sense of rhythm, repetition, and poetic proportion that gives force to such classic verses as these:

"In him we live and move and have our being" (Acts 17)

"Ask, and it shall be given you; seek and ye shall find; knock and it shall be opened unto you" (Matthew 7)

“The Lord bless thee and keep thee. The Lord make his face to shine upon thee and be merciful unto thee. The Lord lift up his countenance upon thee, and give thee peace.” (Numbers 6:24-26)

“In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by it and with out it was made nothing that was made…” (John 1:1)

Following Tyndale

Myles Coverdale (1488-c. 1568) former Augustinian friar and then reformer produced (in 1535) a translation based on the Vulgate, Luther, and Tyndale. Anne Boleyn supported the effort.

John Rogers, under the pseudonym "Thomas Matthew,” published (in 1537 in Antwerp) the Matthew's Bible, based on Tyndale and Coverdale and dedicated to Henry VIII, who had licensed it.

Thomas Cromwell (c. 1485-1540), a strong proponent of the Reformation, sponsored the publication of the Great Bible in 1539, named for its size (15 inches by 9 inches. This Great Bible is fundamentally the Coverdale Bible; the Great Bible is also called the Cranmer Bible because Thomas Cranmer wrote the preface.

Summary – The Reformation & the Bible

And so, what can we say in a summary of what we have discussed over the last few lessons regarding the Reformation and the Bible?

1. The Reformation eventually shattered the religious, cultural, and political unity of Europe.

2. Christendom broke into separate states defined in part by their allegiance to either the Catholic or some Protestant version of Christianity.

3. The translation of the Bible into separate national languages was a critical part of that process.

Next Week

More Englishing

Geneva Bible

Bishops Bible

Douay-Rheims

and the King James