History of the Bible Lesson 2

The Making of Tanak

The story of the Bible begins with the slow, centuries-long gathering of Hebrew writings in ancient Israel. We will first cover the early stages of the formation of TaNaK, the Jewish Bible. The acronym identifies the three components of Torah (the five books of Moses), Neviim (the Prophets), and Ketuvim (the Writings). The literature of ancient Israel, written on scrolls, arose out of the circumstances and needs of the people at different stages of its life. Each composition provides a window to those historical situations. But the compositions, singly and together, also weave an impressively coherent sense of the people's story and of the God who creates the world and reveals through prophets how humans are to honor God by the way they live in God's world.

The acronym identifies the three components of Torah (the five books of Moses), Neviim (the Prophets), and Ketuvim (the Writings). The Hebrew Bible (TaNaK) is the literature of an ancient people that was composed over a long period of time in circumstances that are not entirely clear.

Convictions concerning the divine

inspiration of the Bible are, in both Judaism and Christianity, entirely

consistent with the human and historical origin of the actual compositions.

Discovering the human origins is not at all easy and requires the piecing together of several kinds of evidence and a certain amount of controlled speculation.

So what evidence is available - we have the texts themselves. And that is a rich source that can be mined by scholarly work on known history, linguistics, etc.

We also have archeological evidence - a great deal of it found in recent times.

And we have comparison with other literatures of the ancient near east. Which is important because as we will see the " people of the book", during all of their story, were immersed in the multiple cultures and complex religions of the ancient near east.

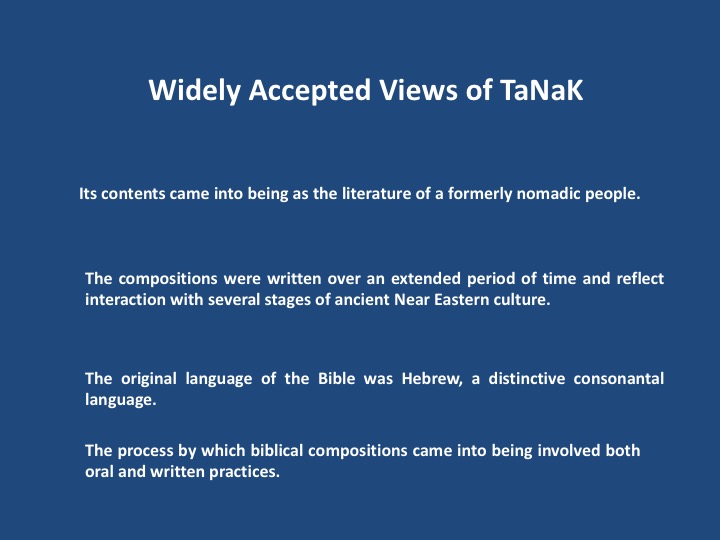

So let's talk about the widely accepted views of the origins of TaNaK. By that we mean the views that most scholars in Judaism and Christianity accept:

Its contents came into being as the literature of a formerly nomadic people that inhabited the tiny strip of land between the ancient empires of Babylon (and Assyria) to the east and Egypt to the west.

This is described in Deuteronomy 26

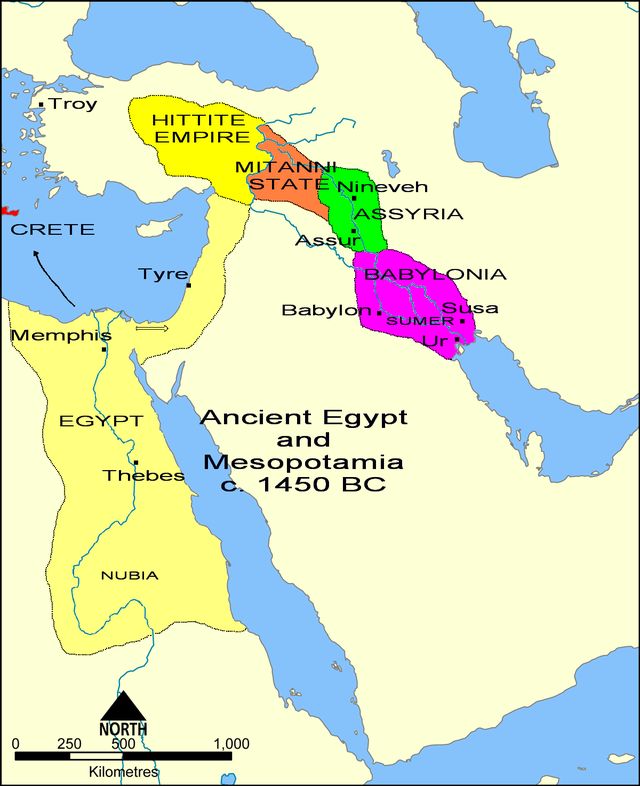

Let's view a few maps to see how this plays out..

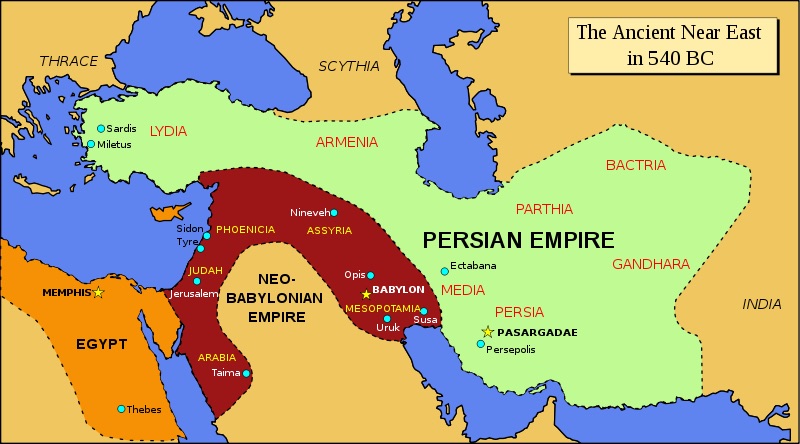

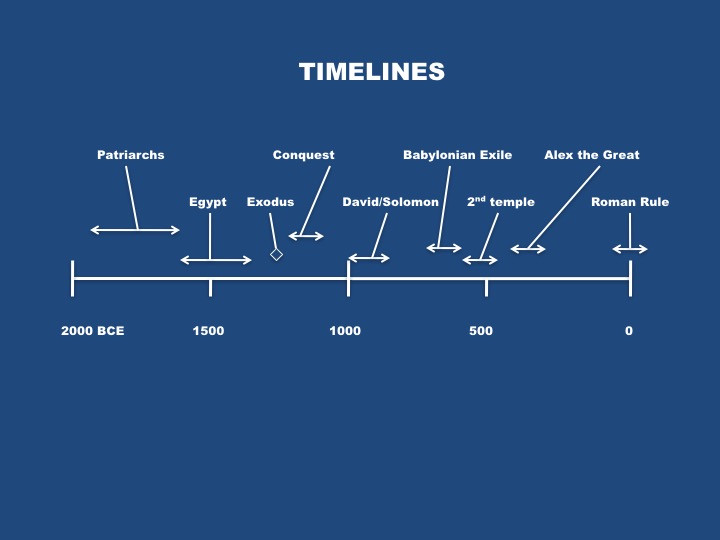

The problem of illustrating what all of the kingdoms looked like in the Ancient Near East is that it depends on which years we are studying. The development of TaNaK occurred over an extensive period of time. This, for example is a map in 1450 BCE. You can see the major kingdoms of Egypt and the territory they controlled in that time (all in yellow).

By contrast - this is a map from 450 BCE. Now there is an empire that scholars called the Neo-Babylonian (red) as well as the now looming Persian empire. Egypt is now reduced in scope. But in these and in all other maps the narrow strip of land known as Canaan was rather insignificant, and for significant periods controlled by larger powers..

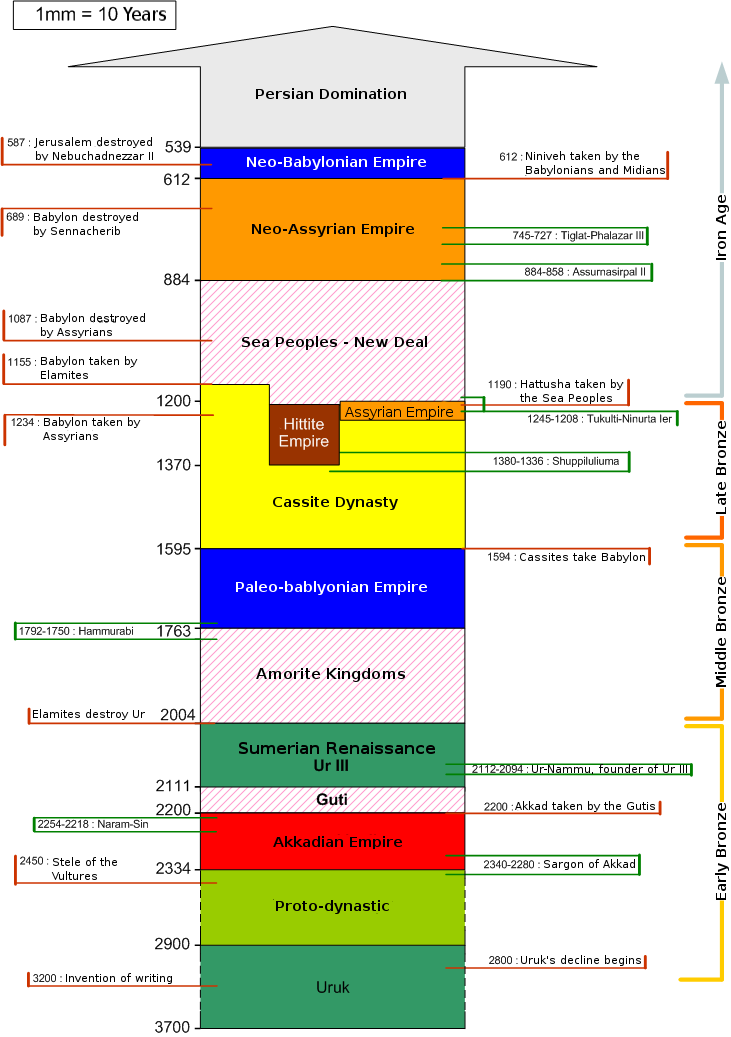

This is a historical chart focusing only on Mesopotamia. It is loaded with information regarding the empires, dynasties, and kingdoms that attempted over time to control the rich agricultural lands of Mesopotamia.

There is much more information summarized in this chart that I have time to teach today, and in fact I could not talk coherently about all of it.

But this is an attempt to conquer on one presentation all of the known history of the empires of the broad area of Mesopotamia. And I would like to use it to give a better understanding of all of the context that preceded and surrounded the development of the Tanak.

Mesopotamia is a a broad region that includes all of the lands supported by the Tigris and Euphrates river systems. Mesopotamia, like Egypt, has been called riverine civilization because of this. Almost all ancient civilizations were riverine civilizations.

A point to notice is that Mesopotamia has a very long history of many empires and kingdoms that dominated it at different times. From the earliest empire to today is 5,700 years, beginning in 3700 BC. But when we make architectural finds we do find written information because writing was invented in the Uruk period, in 3200 BC. It was cuneiform writing, and we will talk about that later.

Moving up to the period after the Cassite Dynasty and the Hittites we see this representation called the Sea Peoples. This is actually the Phoenicians. And they moved in and settled immediately along the coast above Israel ( modern Lebanon). They were much different than many of these major players in that they were not interested in further conquests, but in establishing major sea trade routes to make money. Which they did very successfully. Trading across the entire Mediterranean basin for several centuries. It is believed that the tribes called the Philistines were part of the sea peoples, and that the Philistines we encounter in the story of young David may have been part of their defense forces to ward of possible marauders trying to raid the relatively wealthy cities of the Phoenicians along the coast.

Importantly, the Phoenicians invented the first alphabet, composed of 22 sounds. This alphabet became the alphabet of biblical Hebrew.

The compositions were written over an extended period of time and reflect interaction with several stages of ancient Near Eastern culture.

The original language of the Bible was Hebrew, a distinctive consonantal language with cognates in several other ancient Near Eastern languages; the exception is the second part of the Book of Daniel, which is composed in Aramaic, a dialect of Hebrew.

The process by which biblical compositions came into being involved both oral and written practices.

Oral performance is most obvious in the prophetic literature and in the psalms, but it is likely that writing was also a feature in prophetic activity. The great written narratives may well also have begun as oral recitations in the manner of the folklore of other peoples.

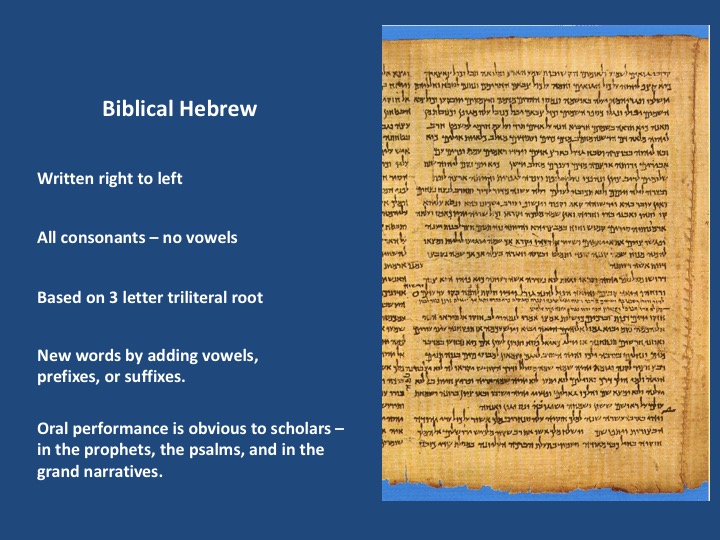

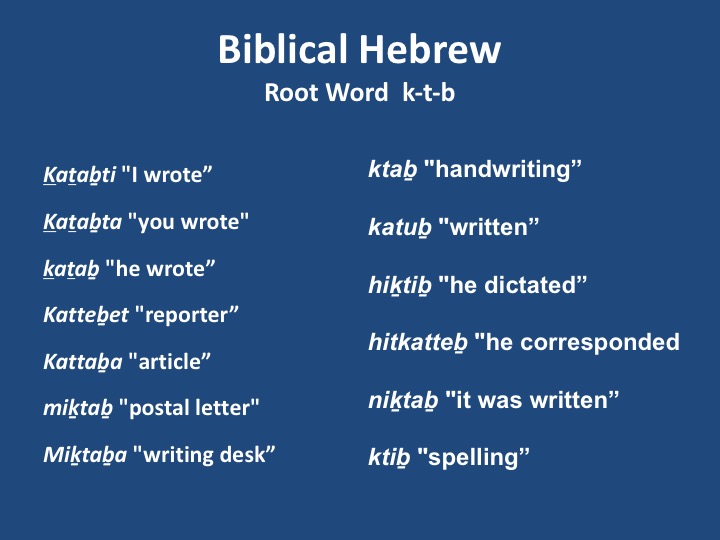

Let's take a quick look at Hebrew and describe what we mean when we say that it was a distinctive consonantal language.

This is sometimes referred to as biblical Hebrew to distinguish it because like all languages Hebrew evolved over time. It is written right to left. Only consonants are used - no vowels. It is based on a 3 letter triliteral root. And we will show how that works.

I might add that the oral performance of Biblical is obvious to Hebrew language scholars; particularly in the prophets, the psalms, and in the grand narratives. This was written to be read aloud.

This is how a triliteral root word can then be extended to many words. The root is k-t-b. These are other words that can be created using the root word with added letters.

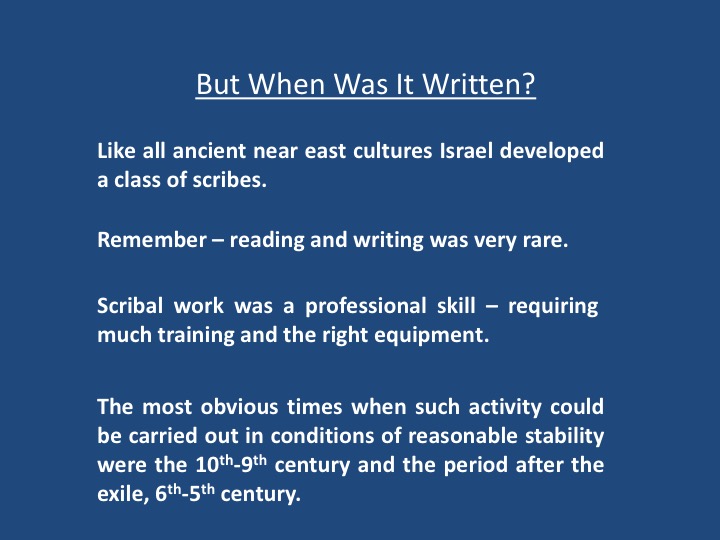

The creation of literature presupposes certain social settings and technical capabilities.

As in other ancient Near Eastern cultures, Israel developed a scribal class whose writing capabilities served both court and temple.

The most obvious times when such activity could be carried out in conditions of reasonable stability were the period following the establishment of court and temple by Solomon and the period after the exile, when a more modest version of court and temple were reestablished.

Thus many scholars surmise that most of the written work on the TaNaK was done in two periods. The period of David and Solomon, and the period of the 2nd temple.

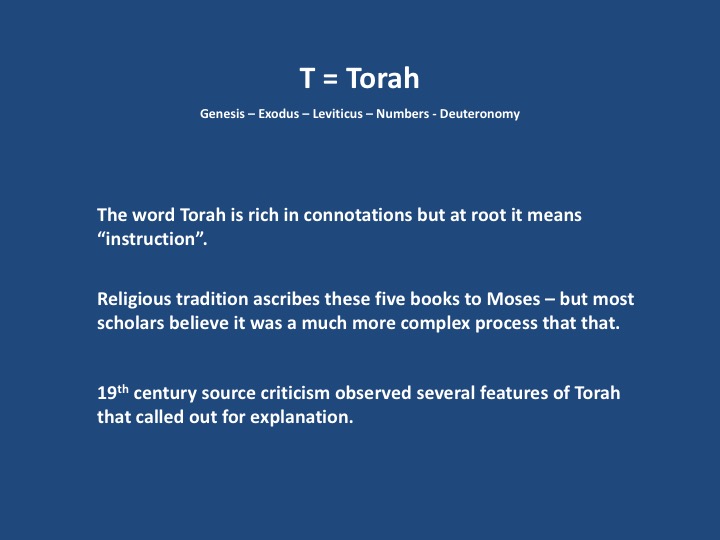

The most authoritative part of the Hebrew Bible is called Torah, or the five books of Moses (Pentateuch). Although religious tradition ascribes these five books (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy) to the prophet and lawgiver Moses (c. 1250 B.C.E.), who led the people out of Egypt, scholars unanimously agree that their composition involved a complex process over a considerable period of time.

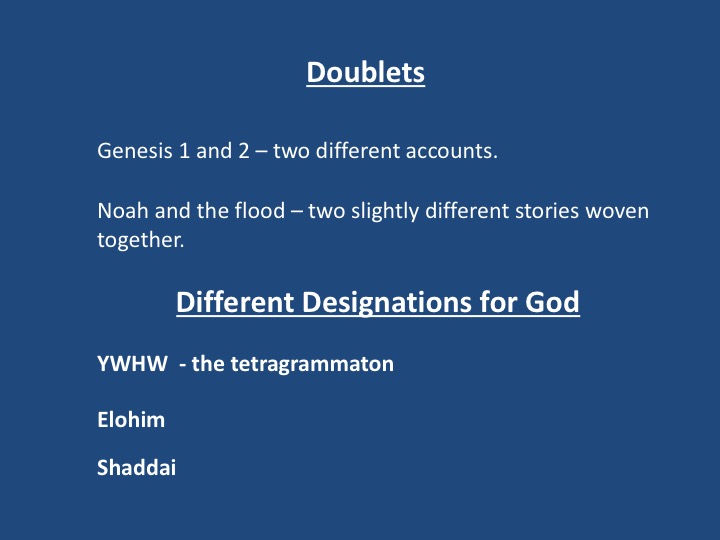

Nineteenth-century source criticism of the Pentateuch observed several features of the five books that called out for explanation (such as doublets and the use of different designations for God).

Although the precise delineation of the sources is debated, many scholars perceive four distinct sources: the Yahwist, the Elohist, the Deuteronomist, and the Priestly.

Even more vigorously debated is the assignment of distinct periods of composition according to the supposed outlook of the sources, with the Yahwist and Elohist representing the more ancient voices (perhaps 10th century B.C.E.), the Deuteronomist representing a reform voice (6th century), and the Priestly outlook serving as editor of the whole.

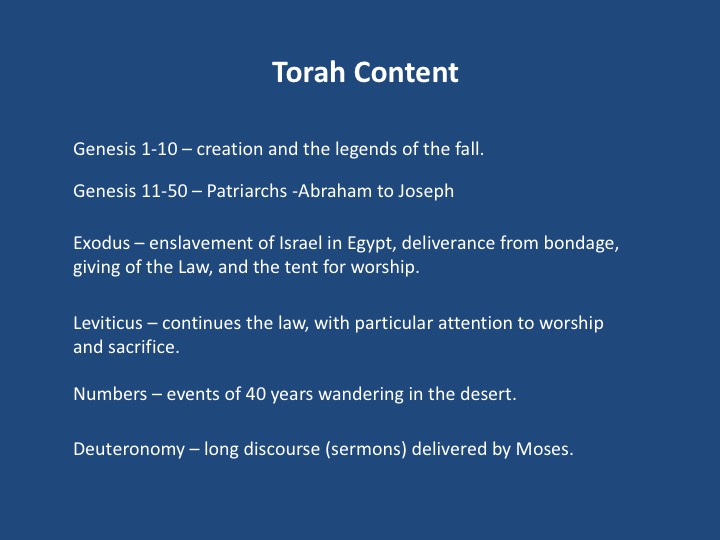

The five books of Moses provide the grand narrative of the formation of Israel as a people and the terms of its covenant with God.

After the account of creation and the legends of the Fall, the stories of the patriarchs from Abraham to Joseph dominate Genesis (Breshit).

Exodus (Shemot) describes the enslavement of Israel in Egypt, the call of Moses and the plagues that come upon Egypt, the deliverance of the people from bondage, and the giving of the Law through Moses, climaxing in the description of the tent for worship in the wilderness.

Leviticus (Wayikra) continues the legislation given to the people through Moses, with particular attention given to the practices of worship, especially sacrifice.

Numbers (Bamidbar) recounts the events of the 40 years of wandering in the wilderness under the leadership of Moses, including the rebellion of the people and the mighty works of God.

Deuteronomy (Devarim) consists of long discourses delivered to the people by Moses before entering the land of Canaan, summoning them to obedience and describing the blessings that came with obedience to the covenant and the curses that came with disobedience.

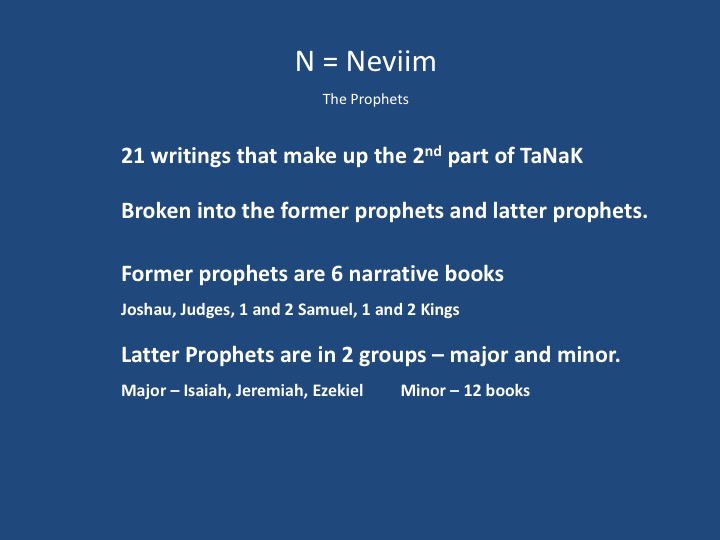

The Prophets (Neviim) are 21 writings that make up the second major portion of TaNaK.

The first portion of the Prophets is made up of six narrative books that continue the story of the people from the time of entering the land (Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings); these books are also called the Former Prophets.

The Jewish Bible counts as the Latter Prophets those spokespersons for God to the people; the term Major Prophets refers to the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel.

The term Minor Prophets is given to a collection of 12 books, not because of their importance but because of their length (Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi).

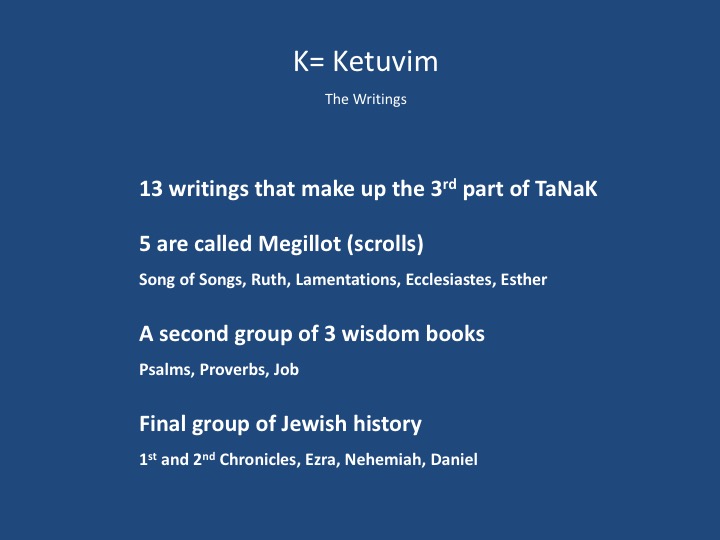

The 13 Writings (Ketuvim) make up the final and least internally organized portion of the Jewish Bible, making a total of 39 compositions. An ancient designation for five of these writings is megillot ("scrolls"): the Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes (Qoheleth), and Esther.

A second loose grouping contains the Psalms, Proverbs, and Job, which can also be seen as wisdom literature.

The final group again takes up aspects of Jewish history: 1st and 2nd Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah, and Daniel.

As I have tried to point out, the TaNaK is a very complex and variegated literature. The most remarkable aspect of this

variegated literature is that in each of its parts and as a whole, it imagines

a world that is at once astonishing and coherent, a world that is in every

respect created by and answerable to God.