History of the Bible Lesson 7

Imperial Sponsorship of the Bible

History of the Bible Lesson 7

Imperial Sponsorship of the Bible

The

story of the Bible we have described so far has been one of a slow organic

evolution over many centuries. The Bible, as we have described it, has been a

growing collection of compositions that gradually were collected into a larger

and larger collection that eventually became canonized. But now we are going to

talk about the first really major event that was a tectonic shift in the Bible

story, as well as in Christianity and Judaism.

The 4th Century - A Turning Point

This change happened very quickly, over less than a decade. To see how huge the change was, let’s talk about some of the contrasts:

In the 3rd century, and the first few years of the 4th century, Christianity was a very persecuted group in the Empire. This was the time of the Emperor Diocletian, who considered the growing new religion to be a threat to his empire.

The reigning religion of the empire was polytheism, that view of reality that there was a pantheon of gods that controlled the various parts of nature that needed to be appeased. And as in all ancient civilizations, that view was the beneficiary of the patronage of the emperor.

The emperors began each day receiving advice from the oracles. They built large edifices to the various gods, not just in Rome, but in the provinces. The worship of the gods was considered by the emperors to be a source of unity to help control the populace, and thus was heavily invested in.

In this environment Jews and Christians competed but Jews enjoyed official recognition. Judaism was a “licensed cult” because it was the religion of a nation. Christianity was instead considered a superstition - because of its outrageous claims - of a resurrected criminal, and no apparent national group.

The 4th Century - A Turning Point (2)

After the 4th century, Christianity was the privileged and powerful religion of the Roman Empire.

Christianity took over from Greco-Roman religion its place as imperial client, with property and power.

Judaism was increasingly marginalized and regarded as a threat to ecclesial and political order.

Christianity itself found its "orthodox" expression within the bounds of empire, while "heretical" forms of Christianity found refuge beyond imperial reach.

The Key Figure - Constantine (274-337)

When Constantine defeated his rival Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge in 313, he claimed that victory was owed to Christ, and he gave, first, tolerance, then, privilege to the Christian religion.

Eusebius's Life of Constantine applauds Constantine's conversion as sincere and as a providential act of God; Constantine is still regarded as a saint by the Eastern Orthodox tradition.

A more likely view - Constantine may have simply recognized the

inevitable triumph of the Christians and decided that it was a more cohesive

religious glue for the empire than paganism; the effect, in any case, was the

same.

The Key Figure - Constantine (274-337)

Like emperors before him, Constantine wanted the imperial religion to secure the unity of the empire and, therefore, demanded unity in Christianity.

He used his imperial influence to settle the Donatist dispute in North Africa in 316, deciding against the schismatics in favor of the Catholics.

His concern for unity also led him to call the Council of Nicea in 325, to settle the rancorous doctrinal disputes caused by Arianism.

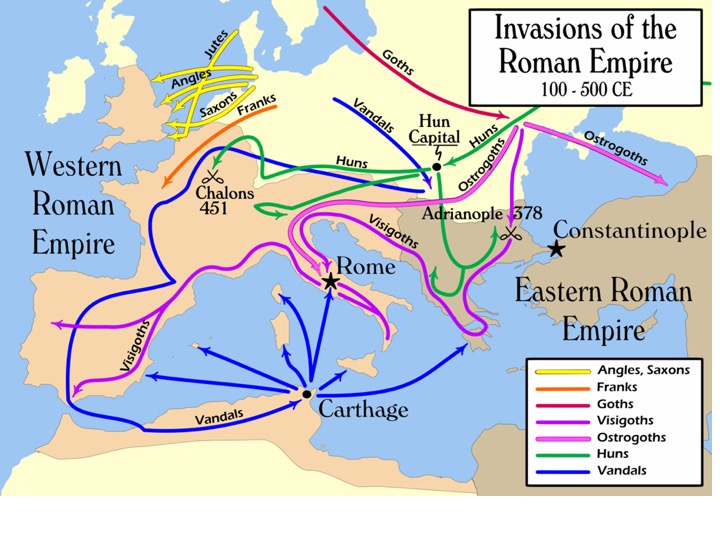

The Migration Period was a time of widespread migrations within or into Europe in the middle of the first millennium AD. It has also been termed the Barbarian invasions. Many of the migrations were movements of Germanic, Slavic, and other peoples into the territory of the then Roman Empire, with or without accompanying invasions or war.

The migrants comprised war bands or tribes of 10,000 to 20,000 people. The first migrations of peoples were made by Germanic tribes such as the Goths (including the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Anglo Saxons, Lombards, Suebi, Frisii, Jutes, Burgundians, Alamanni, Scirii and Franks; they were later pushed westwards by the Huns, the Avars, the Slavs and the Bulgars.

So these movements of peoples were perhaps more migrations then invasions, although the migrations often turned into wars because the Empire tried to keep them out. They were a growing major problem to the western empire. Over time though they absorbed into the culture and in fact became significant parts of the Roman legions, often led by German generals.

So, over time, three crises threatened the Roman Empire: external invasions, internal civil wars and an economy riddled with weaknesses and problems. The city of Rome gradually became less important as an administrative center. It was time to move the capitol and Constantine did not hesitate.

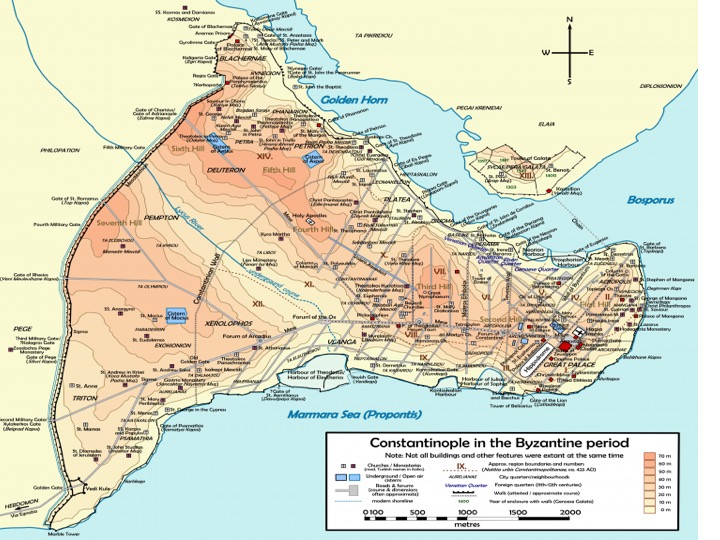

Constantinople in the Byzantine Period

Although he kept some remnants of the old city, New Rome - four times the size of Byzantium-- was said to have been inspired by the Christian God, yet remained classical in every sense. Built on seven hills (just like Old Rome), the city was divided into fourteen districts. Supposedly laid out by Constantine himself, there were wide avenues lined with statues of Alexander the Great, Caesar, Augustus, Diocletian, and of course, Constantine dressed in the garb of Apollo with a scepter in one hand and a globe in the other.

In 330 CE, Constantine consecrated the Empire’s new capital, a city that would one day bear the emperor’s name. Constantinople would become the economic and cultural hub of the east and the center of both Greek classics and Christian ideals. Its importance would take on new meaning with Alaric’s invasion of Rome in 410 CE and the eventual fall of the city to Odoacer in 476 CE. During the Middle Ages, Constantinople would become a refuge for ancient Greek and Roman texts.

With the move of the government of the empire to Constantinople the nature and culture of both the government and the church changed dramatically. Although the official government people called themselves Romans and Constantinople was frequently referred to as the “Second Rome”, this became in many ways a Greek government.

The Key Figure - Constantine (274-337)

By moving his capital to Byzantium (rebuilt and renamed Constantinople)

in 330, Constantine inadvertently opened the way for another sort of division

in the empire.

The Eastern Empire would remain steadfastly Greek in language and culture, and the patriarch of Constantinople would work in close harmony with the emperor for a millennium.

The Western Empire would become increasingly Latin in language and culture; the Church in Europe, under the bishop of Rome (the pope), would be increasingly a political, as well as a religious force.

The result, possibly not anticipated by Constantine, was that the two spheres, the East and the West, grew further apart over time and eventually caused the Great Schism between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. A schism that was never healed.

The Impact of Sponsorship

The decisions of Church councils (and of orthodox bishops) had the backing of imperial force; thus, the canonical declarations of the Council of Carthage (397) or the Festal Letter of Athanasius (367) had a certain coercive effect. The canon decisions were final because they were backed by the Empire's power.

Finally, Constantine put the services of imperial scribes to work in the production of 50 uncial codices that included the entire "Christian Bible" (the LXX and the New Testament), the first time we can confidently speak of the Bible as a "book."

The Fifty Books of Constantine

The Fifty Bibles of Constantine were Bibles in the Greek language commissioned in 331 by Constantine I and prepared by Eusebius of Caesarea. They were made for the use of the Bishop of Constantinople in the growing number of churches in that very new city.

According to Eusebius, Constantine I wrote him in his letter:

"I have thought it expedient to instruct your Prudence to order fifty copies of the sacred Scriptures, the provision and use of which you know to be most needful for the instruction of the Church, to be written on prepared parchment in a legible manner, and in a convenient, portable form, by professional transcribers thoroughly practiced in their art."

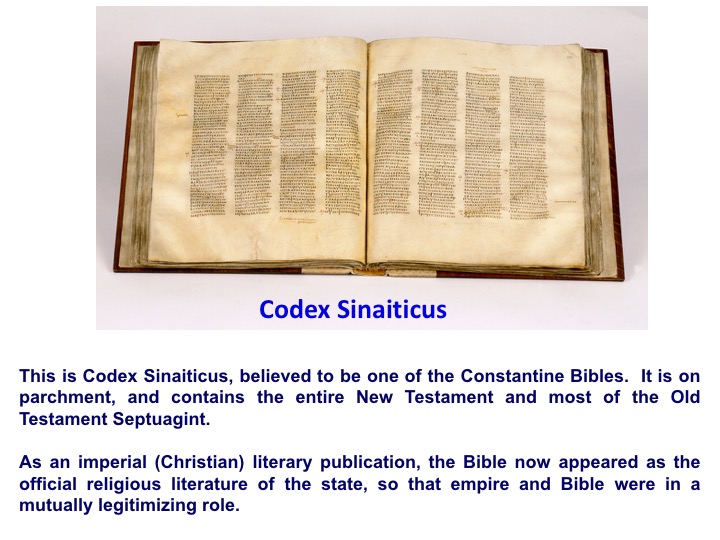

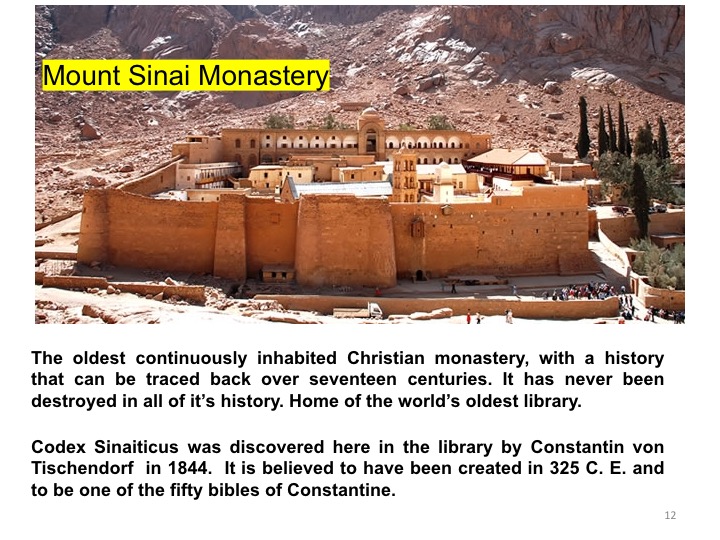

St. Catherine’s Monastery (Mount Sinai)

The oldest continuously inhabited Christian monastery, with a history that can be traced back over seventeen centuries. It has never been destroyed in all of it’s history. Home of the world’s oldest library.

Codex Sinaitcus was covered by here in the library by Constantin von Tischendorf in 1844. It is believed to have been created in 325 C. E. and to be one of the fifty bibles of Constantine.

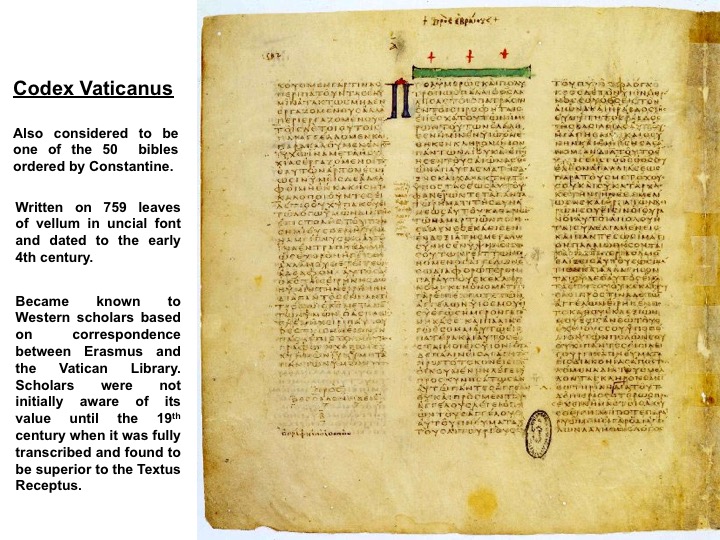

Codex Vaticanus

Also considered to be one of the 50 bibles ordered by Constantine.

Most current scholars consider the Codex Vaticanus to be one of the best Greek texts of the New Testament, with the Codex Sinaiticus as its only competitor

It is written on 759 leaves of vellum in uncial letters and has been dated palaeographically to the 4th century

The manuscript became known to Western scholars as a result of correspondence between Erasmus and the Vatican Library. Scholars were not initially aware of its value until the 19th century when it was fully transcribed and found to be superior to the Textus Receptus

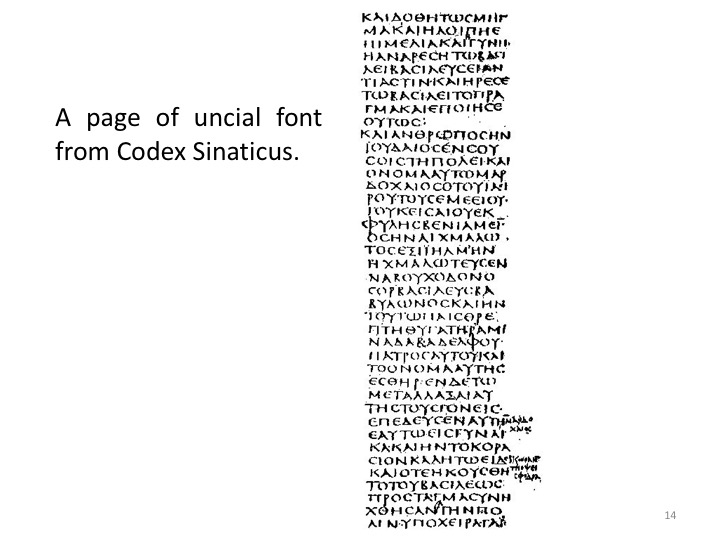

This is a column of uncial font from Codex Sinaticus. This particular font is all caps and designed to be easier to render with more modern inks and parchment. This development led quickly to the future use of this font and parchment for most important papers and marks the beginning of the demise of papyrus.

A New Status for the Christian Bible

Within Christianity - As a book with covers (often adorned) that could be closed and even locked, the Bible served as an object of veneration, whether carried in processions or placed in a shrine.

These expensive books, often bedecked with jewels, often were locked with clasps, and were only open for formal reading. In effect the Bible, for the first time as a book, became an object of worship. This was the beginning of a rather long period all the way until the Renaissance, when the Bible was at its apex in terms of perceived power.

The form of this book, with the Old Testament preceding the New and the two testaments "facing" each other, abetted supersessionist forms of interpretation, in which Judaism and paganism are replaced in God's story by Christianity.

Superseccionist - above or superior. Prophecy vs realization. Tic vs Toc. The preparation and the final result. In effect Judaism was a preparation for the eventual winner - Christianity. Some Christians began to ask - what about these Jews - why are they still here - aren’t they no longer part of history? Superseccisionism gradually became the gounding of anti-semitism.

And the

Jewish Bible, in contrast, did not enjoy official approval or sponsorship although it continued to be read as God's Word for the children of Abraham.

How Did Constantine Alter The Bible?

The question “How did Constantine alter the Bible?” has become popular since the release of The Da Vinci Code. The book reads, “The fundamental irony of Christianity! The Bible, as we know it today, was collated by the pagan Roman emperor Constantine the Great." The movie emphasized that in even stronger imagery.

The answer to the question? He didn’t.

In 325, Constantine called the Council of Nicaea, the first council of the Christian church. The canon was not even on the agenda at Nicaea. The council that formed decisions about the canon took place in 397 in Carthage. This was 60 years after Constantine’s death.

Next week we will turn our attention to many other bibles in many other translations. We tend to get most of our history of the Bible in the west from historians of the Roman Catholic Church. But we will learn next week that there were many competing "bibles" outside of the the control of the empire. Tune in next week.