Joseph Story - and It's Egyptian Background

There are two classes remaining in our summer Genesis series – today’s story and next weeks wrap-up. Today we will cover the last extended section of Genesis, which is often called the Joseph story.

And I want to do two things today – tell that story and in doing so try to show what a great story it is – often called a novella because it is less episodic than the other patriarchal stories. But while telling the story I want to show and compare the cultural elements of that story to show the many contact points between that story of the people of Israel and what we now know about ancient Egypt. Because unlike what we said earlier about the other patriarchs and the lack of historical evidence from the land of Canaan to compare those against – we have a wealth of information of ancient Egypt – based on over two centuries of archeological research. Because Egypt for two centuries was a place that archeologists could spend large amounts of time working without being shot at. And the Egyptians were much more prone to preserving their history than the cultures of Mesopotamia and particularly the Land of Canaan.

And what we find is that the

ancient Israelite author of Genesis had an intimate knowledge of Egyptian

culture and language and that, most likely, he expected his Israelite audience

to know many of these details.

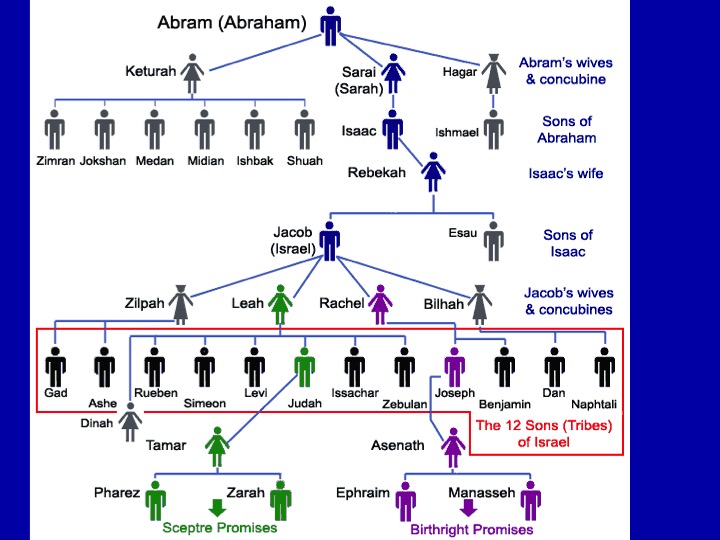

O.K. – let’s start with our scorecard. The growing family of Abraham. And let’s remind where Joseph fits in.

The two youngest sons of Jacob

were Joseph and Benjamin. They also were

true brothers – that is they had the same mother – Rachel.

The story begins in Genesis 37.

The story is set up

here. And immediately there is conflict.

And we learn that the young Joseph is a tattletale on his brothers. Furthermore

we learn that Joseph’s now elderly father Israel played favorites – something

Jacob should have know better about because his father Isaac had also played

favorites with his sons.

And the story continues as Israel sends Joseph in search for his brothers. And we here learn the now familiar story of how Joseph’s brother’s plan to get even with him.

The original idea, as you can see, is to kill

Joseph. But as you may remember Judah suggests a different plan when he sees

some traders coming and suggests that rather than kill Joseph they make some

money on the deal and sell him into slavery.

We will not read the entire story of the brother’s capture of Joseph and throwing him in a well. But we see beginning in verse 28 what the brothers finally did.

So now Joseph is in Egypt and we encounter our first Egyptian name. The very interesting story that follows describes the ongoing adventures of Joseph in Egypt. He rises quickly in the house of Potiphar and eventually is put in charge of his house. Sometime after that Potiphar’s wife tries to seduce Joseph and when he rejects her advances she accuses him of attempted rape and Joseph is thrown in prison. After he spends a great deal of time in prison he becomes famous there as an interpreter of dreams. And I might add that dream interpretation was a big deal in Egyptian culture (not so in Israelite culture). So when the Pharaoh has two vivid dreams that neither he nor his experts can fathom Joseph is hauled out of prison for an audience with the Pharaoh.

As you may remember from the story, Joseph then quickly interpreted the dreams and as a result impressed the Pharaoh and Joseph was brought into his government as an important person.

Potiphar is in fact an

authentic Egyptian name so let’s break from the story for a while to look at

some of the Egyptian names and customs that we see in this story.

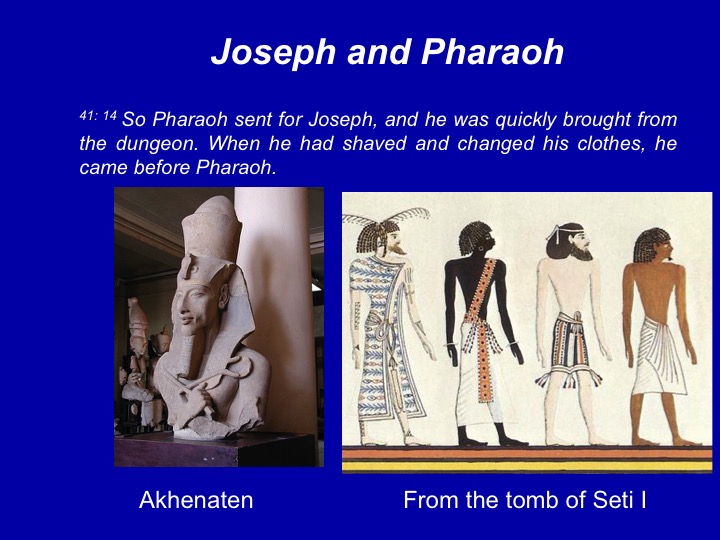

And as Joseph is summoned before the Pharaoh we read this in Genesis 41:14. Note that Joseph had to shave before meeting Pharaoh.

Two images – the first is a recovered statue of Akhenaten – the supposed father of King Tut. It shows the typical Egyptian custom of staying clean shaven (except for a either a false beard as shown here) or maybe a very small goatee.

By contrast the relief from

the tomb of the Pharoh Seti I is supposed to depict first a Libyan, a Nubian,

an Asiatic, and an Egyptian. Asiatics

was a general term used in Egypt for anyone from the Northeast – including the Land of Canaan

and Mesopotamia. It is well recorded that the Egyptians were highly suspicious

of foreigners.

The names in the story are also authentically Egyptian, including Potiphar (whom we encountered in the previous lecture), Potiphera (a variant form of the same name, the father-in-law of Joseph), Asenath (Joseph's Egyptian wife), and Zaphenath-paneah (Joseph's Egyptian name, meaning something like "the god has spoken and he has life").

Names in antiquity typically have the name of the deity whom one worships embedded into them.

1. Potiphar, Joseph's master, and Potiphera, Joseph's new father in-law, are variants of the same name, meaning "given by Ra."

2. Earlier we referred to Akhenaten, and showed his statue. The god Aten appears in his name.

And lest you think this habit of putting God’s name in your name is exclusively Egyptian – let’s look at some Hebrew names.

In Hebrew, those names that end in "yah" reflect the fact that these individuals worshiped Yahweh-"yah" is a shortened form of Yahweh-as you see at the end of names such as Isaiah and Jeremiah. If you have "el" in a biblical name, this is a shortened form of the word Elohim, as you get in at the end of Samuel, and Daniel, or at the beginning of Elijah and Elisha.

Joseph's father-in-law is a

priest in the city of On, an authentic place in ancient Egypt, the center of

worship of the sun-god Ra, and, thus, later called, most appropriately,

Heliopolis by the Greeks (located in the northern suburbs of modern Cairo).

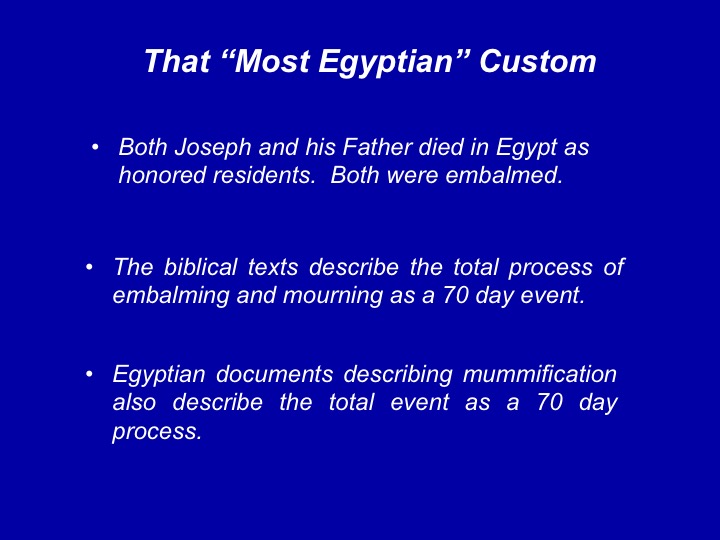

And finally – that most Egyptian custom is attested to in this story.

We are talking about the ancient Egyptian custom of mummification. In Genesis both Joseph and his father died in Egypt as honored residents and both were embalmed.

The writer of Genesis knew Egyptian customs very well!

As

an aside only the Egyptians has a strong belief in a positive afterlife. The Torah for example does not discuss this

at all.

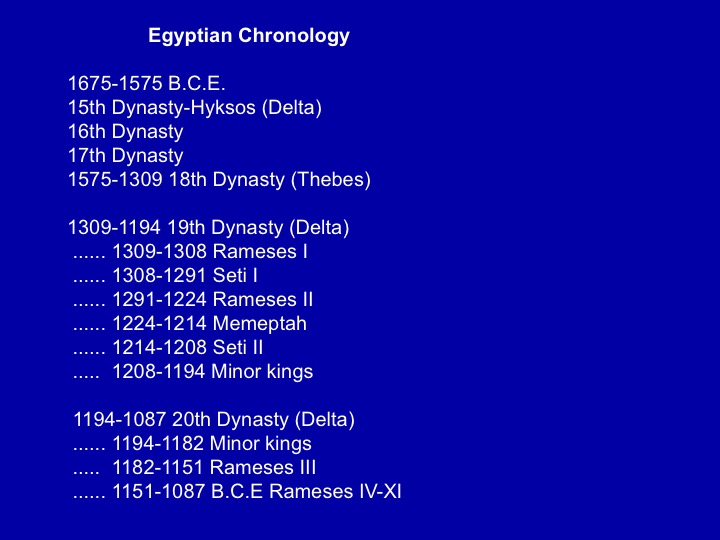

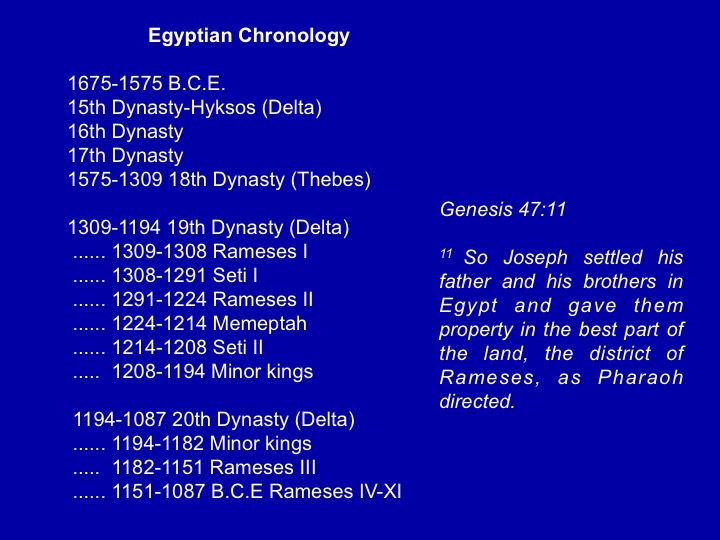

Unlike the land of Canaan we have a rather detailed chronology of the various dynasties of Egypt.

Unfortunately, to the

consternation of biblical historians, the Joseph story never gives the names of

the Pharaoh that Joseph served. There

are two predominant theories – that the Pharaoh that Joseph served was from the

Hyksos dynasty or was Seti I in the 19th dynasty. Both arguments have some good reasons for

their hypothesis – but we do not know conclusively.

The Biblical argument for

Seti I is this verse in Genesis that indicates that Isaac's family settled in

the District of Rameses. It seems unlikely that there would have been a

district of Rameses until the Rameses family name appeared in the 19th

dynasty.

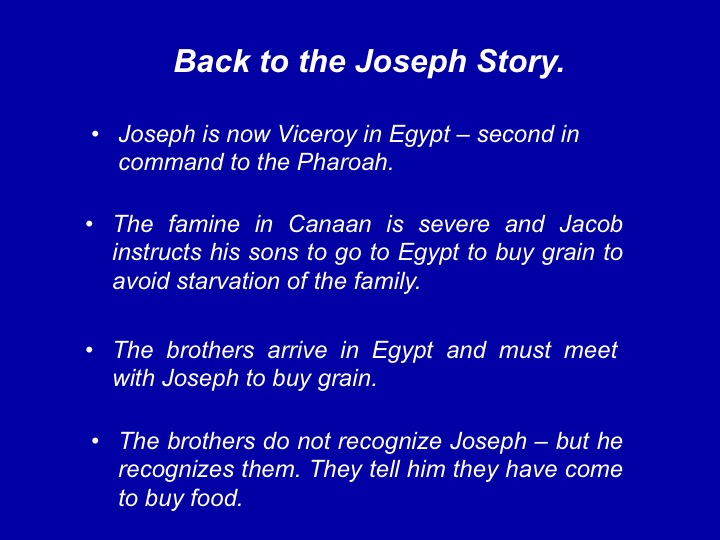

And now we return to the Joseph and review the elements we already know from this well told story.

The famine, that Joseph had foretold in his dream interpretation has now happened, but Egypt is prepared for it and Canaan is not. Jacob is forced to send his sons to Egypt to buy grain to save his family. They meet with Joseph to buy grain. Note that they do not recognize him. Not only is he older, but he is a clean shaven Egyptian.

But importantly, Joseph does know them.

And it continues.

And continues.

And continues.

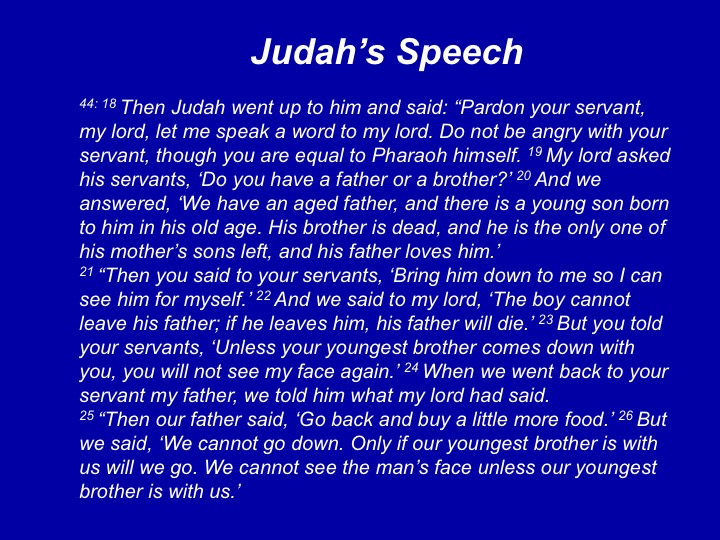

And now we read my favorite story in the Old Testament. No other speech in the Torah is more than 2 or 3 verses. This is 17 uninterrupted verses in which Judah “grows up” as a man. Let’s read it together.

And the speech continues.

In the end Judah offers to stay behind as a slave

in order to save Benjamin and by inference save his father from dying of grief. And as we will see, it got to Joseph.

And now for the first time Joseph revels who he is to his brothers.

They are stunned and frightened. Surely their powerful brother will now take his revenge for what they did.

But Joseph instead tells them that all of this was

God’s plan to save the lives of the people of Israel (Jacob).

God is involved and God is in control. Joseph’s statement is at the pivot point of the chiasm of the Joseph story. In other words this is the central message. And just to emphasize it Joseph returns to it several chapters later at the end of Genesis in chapter 50. Jacob had just died and once again the brothers feared Joseph might take revenge on them. But Joseph again explained what really happened.

The Message - the hand of God is always to

be seen in the history of Israel.

Next week we will wrap up and reflect on everything

we learned in the tour of Genesis.