Jesus and the Gospels Lesson 1

Mike Ervin Introduction

Jesus and the Gospels

To most Christians the Gospels represent the stories they love the most. And the best source to better understand Jesus of Nazareth.

But maybe there are better ways to read them.

We are going to talk about how we might engage the Gospels as literature, which is probably how the early church engaged them.

And since it is usually the case that context is as important as text when reading scripture, we are going to try to give you some context today, before we start engaging the Gospels.

Questions We Will Consider Today

How many Gospels did the early church produce?

When did we get the Gospels?

How did we get the Gospels?

Why did we get the Gospels?

Jesus and the Gospels. Early Christianity was prolific in its production of Gospels. The Gospels are fascinating literary compositions in their own right, and they raise puzzling questions about the figure they portray and about the religious movement, Christianity, that produced them. What accounts for the diversity of images? Is it possible to speak of a single Jesus when accounts about him are so various?

Our Approach in This Series

There have been a number of approaches to interpreting the gospels.

The most common approach is through history.

History approaches treat the gospels shabbily.

Our approach will not primarily be historical, but literary.

Jesus and the Gospels

Why

Did Scholars Want to Find the Historical Jesus?

That Jesus of Nazareth is a figure

deserving study is not difficult, and usually not necessary, to demonstrate.

Jesus is the single most pivotal figure in the shaping of Western culture: One

cannot claim to understand the West without coming to grips with Jesus.

He is the founding figure of the largest world religion; understanding the

religious behavior of two billion people involves understanding their

allegiance to Jesus. Even though Christians are deeply divided on many points,

and even disagree on the implications of this one, they all agree that the

human Jesus is the measure of their identity. By any standard, Jesus is one of

history’s most

fascinating,

compelling, and illusive figures.

Given that Jesus is a historical figure,

many assume that the methods of history provide the best access to learning

about him. Since the Enlightenment, a major project of religious scholarship

was the “quest for the historical Jesus” (see Albert Schweitzer). That quest

involved a decision concerning the nature of historiography: It cannot include

the miraculous. The first classic work in this quest was The Life of Jesus

Critically Examined, published in 1835 by David Friedrich Strauss, who made the

fundamental decision that history has to do with human events in time and

space. It also involved a search for the earliest (and least dogmatically

tainted) source about Jesus. But all the sources turned out to be dogmatic.

Although the quest failed to find a historically satisfying Jesus, it did

clarify the character of the Gospels.

Jesus and the Gospels

Why Doesn’t a History Approach Work?

Recorded history or written history is a historical narrative based on a written record or other documented communication. It contrasts with other narratives of the past, such as mythological, oral or archeological traditions.

For broader world history, recorded history begins with the accounts of the ancient world around the 4th millennium BC, and coincides with the invention of writing.

For some geographic regions or cultures, written history is limited to a relatively recent period in human history because of the limited use of written records.

Moreover, human cultures do not always record all of the information relevant to later historians, such as the full impact of natural disasters or the names of individuals; thus, recorded history for particular types of information is limited based on the types of records kept. Because of this, recorded history in different contexts may refer to different periods of time depending on the topic.

The interpretation of recorded history often relies on historical method, or the set of techniques and guidelines by which historians use primary sources and other evidence to research and then to write accounts of the past. The question of the nature, and even the possibility, of an effective method for interpreting recorded history is raised in the philosophy of history as a question of epistemology. The study of different historical methods is known as historiography, which focuses on examining how different interpreters of recorded history create different interpretations of historical evidence.

Jesus and the Gospels

Our Focus

Our focus, in short, is not simply on Jesus but also on the Gospels as literary compositions.

We want to know how they came to be, how they are related to one another, and how they communicate through their literary structure, plot, character development, themes, and symbolism.

It is as literature that the Gospels

influenced history. And it is through literature that present - day readers and

believers encounter Jesus.

Jesus and the Gospels

Context!

As mentioned earlier, when reading scripture, understanding the context helps us understand the text. What was going on behind the scenes of the stories that led to the Gospels we have.

So we will begin on the next slide with a

map, and use it to begin to introduce some of the cultural context that was

going on as the Gospels were under development.

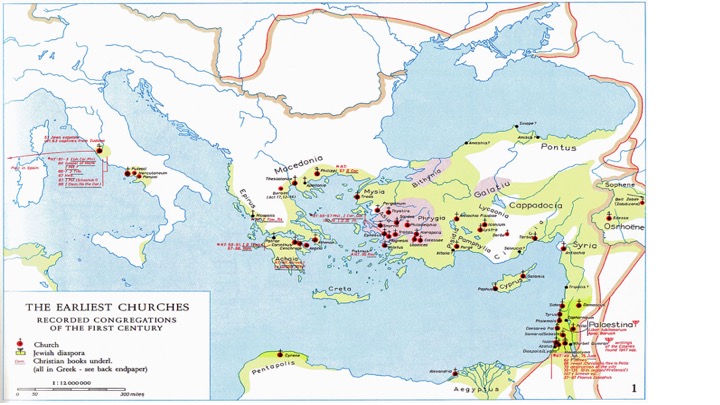

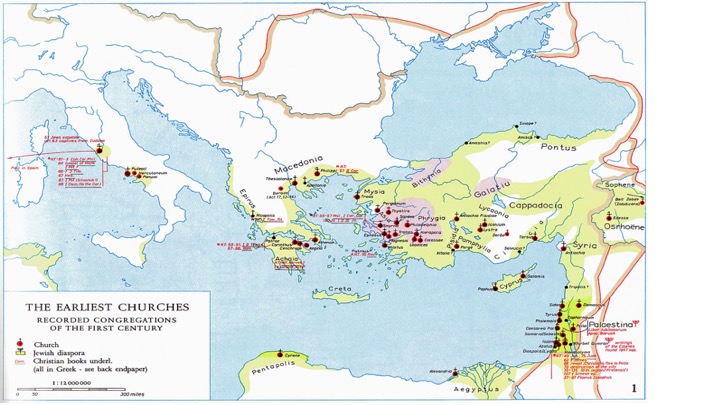

Initial Growth of Christian Churches

The early growth from 30-70 AD was nothing short of phenomenal.

Christianity had no power base (in the conventional sense) and was in fact suspect to the Roman government.

There was no central home church training missionaries. In fact the Jerusalem church was very poor as evidence of Paul’s trying to take up a collection from his Greek churches to take back to Jerusalem.

These

churches were being established in multiple different churches with multiple

different languages.

And yet Christianity continued

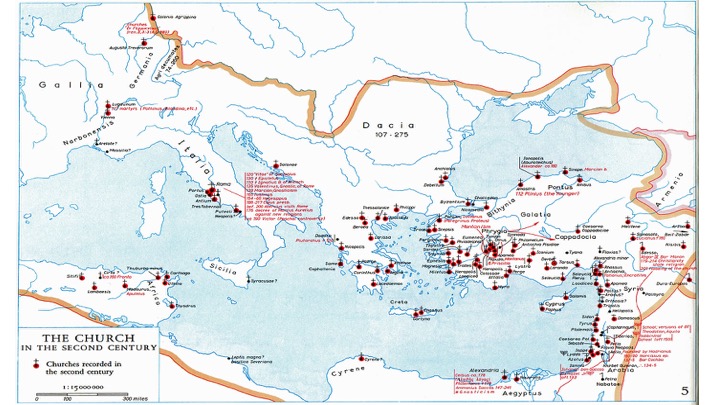

And if we briefly look at the second century – the growth of Christianity after the destruction of the Temple did not abate.

The number of recorded Christian churches more than doubled.

Jesus and the Gospels

Context – The Matrix of Greek & Jewish Worlds

Most of the lands just shown were under Roman rule. Yet there was a relatively small influence of that in early Christian writings.

The Greek and Jewish influences were much more evident. The Romans had adopted many aspects of Greek civilization. Greek was the official language of the Roman Empire during this entire period.

Jesus was a Jew. Christianity began as a Jewish sect, and was part of the symbolic world of Torah. But all the early written Christian material was in Greek. And Jews had been reading read their Bible in Greek (the Septuagint) for more than 200 years.

Understanding the development of early

Christianity requires a good understanding of these dominant Hellenistic and

Jewish cultures.

Let’s return to the map.

Regarding the Jewish influence, note the lands represented by the light green coloring. This represents the Jewish Diaspora – the dispersion of the Jews outside of Palestine.

We should not forget that our best estimates of this is that in the first century there were about 2 million Jews living in Palestine – the place of all of Jesus’s ministry. But there were more than 5 million Jews living outside of Palestine. And this dispersion had been in place for many centuries.

There was no Temple in the Diaspora – no place for the traditional mode of worship involving temple sacrifices.

Diaspora Judaism was a well established religious experience practiced in a different way. And in all of the Diaspora that religion worked and thrived within a strong Hellenistic Greek speaking culture. Im most of the Diaspora the ability to read biblical Hebrew was lost – remember their Bible was the Septuagint - a Greek text.

And Another map

This is a map of known Jewish synagogues in the 1st and second centuries.

It is striking that the locations of these synagogues corresponds to the locations of the early Christian churches.

This is probably not surprising in that as we follow the missionary work of Paul we notice because Paul was a devout Jew, his letters and the book of Acts frequently report that as he carried out his work by visiting Jewish synagogues to proclaim his message. And he not only was able to convert Jews to messianic Jews, he also was able to recruit what was called the God-fearers, Gentiles who frequented the synagogues attracted to the ancient religion of Israel.

We sometimes forget that 1st century Judaism was still a growing religion that actively encouraged conversion of Gentiles to Judaism.

Jesus and the Gospels

How Did We Ever Get Gospels?

We need to remind ourselves that the Gospels were not composed by eyewitnesses immediately after the resurrection and used by preachers – the rather amazing growth of the early church between 30 and 70 AD was accomplished without a “new testament” book.

So how and why did we finally get “The Gospels”, telling us about the life of Jesus some 40-60 years after the resurrection.

Before the appearance of the written 4 Gospels near the end of the 1st century, the memory of Jesus was transmitted in widely scattered Christian communities via oral transmission and some scribal work.

Jesus and the Gospels

How Did We Ever Get Gospels?

In Hellenism and Judaism alike, oral tradition and scribal activity were closely intertwined. Letters, for example, are written and sent to others, but they are often dictated and are read out loud to their recipients. Similarly, an orator or teacher could prepare notes for an oral presentation, and these could be inscribed in writing as notes by hearers.

The scholarly approach to figuring out how the oral tradition and scribal activity evolved is called form criticism. Form criticism devotes itself to the analysis of the oral tradition that precedes the Gospels but is also found within them.

How Did We Ever Get Gospels? (3)

Stories and sayings in the Gospels appear most often in the form of isolated units (pericopes). These pericopes appear in different places in the Gospels; thus, they are units that can be moved around.

Regarding the passion narratives, they are the most detailed and consistent in their presentation, the passion account was probably the first part of the Gospel tradition to reach the form of a sustained recital, whether oral or written.

And many scholars think that many of Jesus’s

sayings reached a written stage (called Q) before the composition of the first

narrative Gospel. We

have never found a copy of Q.

Jesus and the Gospels

Why Compose Gospels?

The composition of full narrative Gospels represents a fundamental shift in early Christian consciousness. The meaning of the word Gospel changed.

When Paul uses the Greek word euangelion, which means the “good news”, and is translated in most bibles as “the Gospel” he refers not to stories about Jesus, but to the kerygma, the proclamation of God’s work in the death and resurrection of Jesus.

But over 20 years after Paul’s death the term Gospel took on a completely new meaning to most Christians, now referring formally to a written composition and to what Jesus did and said in the power of God. The ministry - and, eventually, the birth and infancy of Jesus are now included in the meaning of the “good news.”

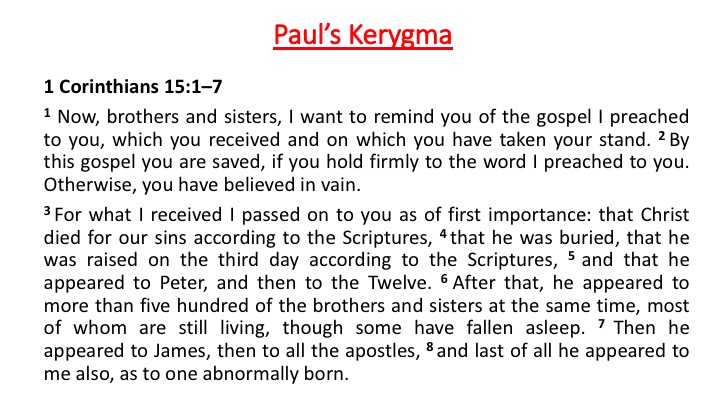

Paul’s Kerygma

So what was Paul’s kerygma – his constant proclamation?

1 Corinthians 15:3–7

15 Now, brothers and sisters, I want to remind you of the gospel I preached to you, which you received and on which you have taken your stand. 2 By this gospel you are saved, if you hold firmly to the word I preached to you. Otherwise, you have believed in vain.

3 For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, 4 that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, 5 and that he appeared to Peter, and then to the Twelve. 6 After that, he appeared to more than five hundred of the brothers and sisters at the same time, most of whom are still living, though some have fallen asleep. 7 Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles, 8 and last of all he appeared to me also, as to one abnormally born.

To Paul – this was the Gospel. To later Christians the word Gospel took on a different meaning once the Gospels began to appear after the death of Paul, Peter, and most of the early church leaders.

Jesus and the Gospels

Why Compose Gospels? (2)

The reasons for finally composing full narrative Gospels after such a long period of oral tradition must have been real and weighty.

A number of hypothesis have been floated by scholars to try to explain why the Christian movement “rather suddenly” seemed to need Gospel stories.

The most probable incentive to composing Gospels was a combination of factors connected to the Jewish War with Rome in 67–70.

By the year 70, many eyewitnesses

especially such leaders as Peter and Paul—had died.

Jesus and the Gospels

Why Compose Gospels? (3)

In the Jewish War, the Christian community abandoned the city of Jerusalem, meaning that the symbolic center of the movement was lost along with the rootedness of the Jesus tradition in Palestine.

Relations between messianic and non-messianic Jews were strained by the events of the war.

Christianity was becoming increasingly Gentile in makeup, again threatening the Jewish roots of the movement.

This cluster of circumstances made it important to “remember Jesus” in a new and more authoritative manner, both to preserve the best of the oral tradition and to enable future generations to encounter a Jesus who was recognizably the one proclaimed by the first generations.

The Nature of the Gospels

If we recognize all of this pre-history of the Gospels, including the earlier oral and scribal tradition, it can help present-day readers appreciate the complex multilayered character of the Gospels.

Each of the gospel writer’s wanted to address the events of Jesus’s life, death and resurrection, they wanted to address the concerns of the church that had remembered and transmitted those events, and each gospel writer wanted to address their own concerns by the way in which they organized the memories and scribal notes each had access to.

Thus we can maybe appreciate the choices made by the evangelists (both canonical and apocryphal) in their compositions, because the oral tradition made possible a number of different selections of material, yielding a number of different portraits of Jesus.

Harmonizing the Gospels – the Diatessaron

We mentioned earlier that the various Gospels represent a sometimes bewildering portrayal of Jesus.

This is not just a modern concern of the Enlightenment but was being discussed in early Christianity.

One rather prominent response to this was the Diatessaron, produced by Taitian, an Assyrian early Christian apologist and ascetic, in about 160-175 AD.

Taitian sought to combine all of the textual material he found in the 4 Gospels into a single coherent narrative of Jesus’ life and death.

The final work is about 72% the size of the 4 Gospels put together.

The Diatessaron

In the early church the 4 Gospels at first circulated independently, with Matthew as the most popular.

It is not clear whether Tatian intended the Diatessaron to supplement or to replace 4 Gospels, but both outcomes came to pass.

The Diatessaron became the standard lectionary used in worship in some Syriac-speaking churches from the late 2nd to the 5th centuries, before giving way to the 4 Gospels.

During that time the Diatessaron circulated widely as a supplement to the four Gospels in the Latin west, especially the Latin version.

Eventually though, the Diatessaron faded and the canon became the four Gospels we now know.

A Study Outline Jesus and the Gospels

With all of this “context” setting as a background, we will begin in two weeks to:

- Examine the four canonical gospels in a literary fashion to try to interpret the convictions of the writers concerning Jesus.

- And finish with a brief review of the apocryphal Gospels.