New Testament Canon Lesson 3

Chris Knepp

Text of Lesson 3

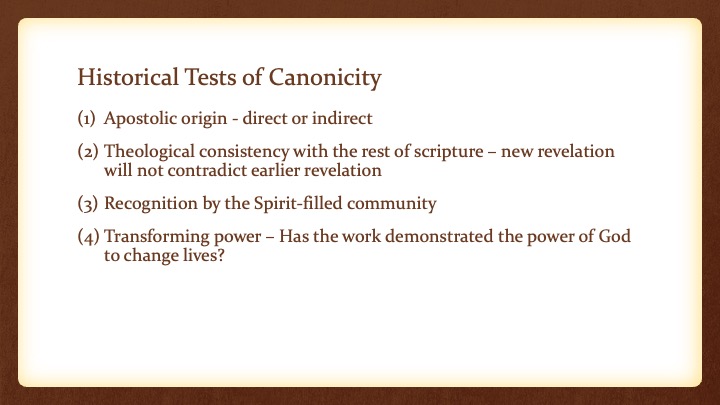

Historical Tests of Canonicity

(1) Apostolic origin - direct or indirect

(2) Theological consistency with the rest of scripture – new revelation will not contradict earlier revelation

(3) Recognition by the Spirit-filled community

(4) Transforming power – Has the work demonstrated the power of God to change lives?

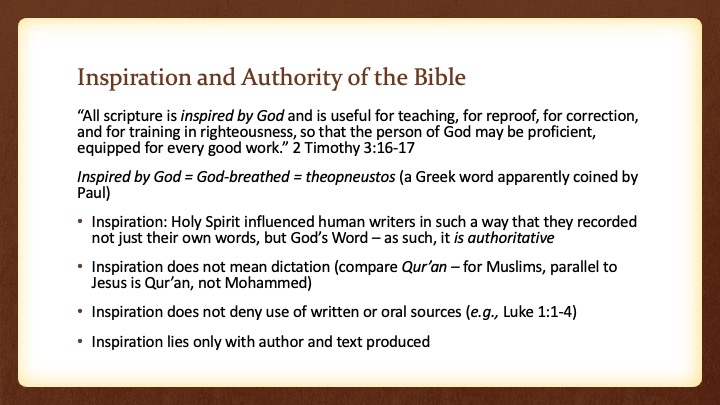

Inspiration and Authority of the Bible

“All scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, so that the person of God may be proficient, equipped for every good work.” 2 Timothy 3:16-17

Inspired by God = God-breathed = theopneustos (a Greek word apparently coined by Paul)

Inspiration: Holy Spirit influenced human writers in such a way that they recorded not just their own words, but God’s Word – as such, it is authoritative

Inspiration does not mean dictation (compare Qur’an – for Muslims, parallel to Jesus is Qur’an, not Mohammed)

Inspiration does not deny use of written or oral sources (e.g., Luke 1:1-4)

Inspiration lies only with author and text produced

The Textual Problem: We Have No Autographs

• It means the original biblical text penned by the author

• No autograph of a biblical text has survived

• So, we must reconstruct the autograph as closely as possible from existing manuscripts

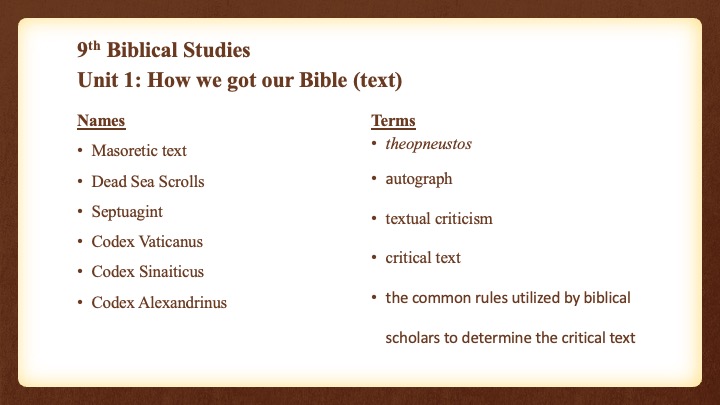

Learning Objective

• To be able to complete the following statement using the names and terms listed above:

• “Even though we do not have any of the autographs, I have confidence that the Bible I read accurately conveys the original text of the scriptures because….”

How Has the Biblical Text Been Preserved?

The Short Answer!

• “There are thousands of variant readings throughout the OT and NT, but most are very minor (many in the OT involve spelling), and no doctrine of the Christian faith rests on any of these divergences. Furthermore, the wealth of manuscript evidence and the strong consensus among scholars concerning the practice of textual criticism, together confirm the accuracy and reliability of the text of Scripture.” Mark Strauss, “Introducing the Bible,” IVP Introduction to the Bible

How Did We Get the Text of the Bible We Have Today?

Before invention of printing press (c. 1440), copies made by hand.

Errors inevitably resulted

More copies, more errors (think of “telephone game”)

Eyeglasses not invented until c. 1375!

No two copies are exactly alike. How can we be sure we have what the divinely inspired authors actually wrote?

The Science and Art Of Textual Criticism

“The goal of textual criticism is to work backwards from the many surviving manuscripts, reconstructing the autograph as closely as possible. This is accomplished by judging where scribes made unintentional errors or intentional changes. Textual criticism is a science, in that there are rules and principles which govern the procedure. It is also an art, in that nuanced decisions must be made from the best evidence. While one hundred percent reliability is never possible, there is widespread agreement among scholars today that the text of the Bible has been preserved and restored with a very high degree of reliability.” Mark Strauss, “Introducing the Bible,” IVP Introduction to the Bible

Textual Criticism: Two Kinds of Evidence

- External: Relates to date and value of manuscripts. Most important are Codex Vaticanus (4th century), Codex Sinaiticus (4th century), and Codex Alexandrinus (5th century). Earliest manuscripts are most reliable.

- Internal: Refers to tendencies of copyists – what kinds of mistakes did they tend to make?

Choose the reading that best explains how other readings might have been made

Shorter reading is usually original – copyist more likely to add clarification than drop it

“Harder reading” is usually original – copyist more likely to smooth over a difficulty than create one

Applying these principles produces the “critical text.”

Some Classic Examples:

Do Modern Translations “Cut” Words Out of the Bible?

Mark 9:29 And he said unto them, This kind can come forth by nothing, but by prayer and fasting. (KJV)

Mark 9:29 And he said to them, “This kind cannot be driven out by anything but prayer.” (RSV)

Luke 4:4 And Jesus answered him, saying, It is written, That man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word of God. (KJV)

Luke 4:4 And Jesus answered him, “It is written, ‘Man shall not live by bread alone.’” (RSV)

Not to mention Mark 16:9-20 (post-resurrection appearances of Jesus) and John 7:53-8:11 (woman caught in adultery). Have you noticed the annotations in your Bible for those passages?

OT Textual Evidence - The Masoretic Text (MT)

Standard Hebrew text of OT is Masoretic text

Jewish scholars known as Masoretes meticulously standardized and copied texts from 6th to 10th centuries A.D.

Good news: Masoretes worked precisely and accurately, producing high level of consistency

Bad news: Tended to destroy old copies to protect them from defilement

Result: Oldest copies are from 10-11th centuries, over 1000 years since last OT book written (oldest complete copy is Leningrad Codex, 1008 A.D.)

OT Textual Evidence

The Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS)

Discovered from 1947 on in caves near Qumran on shores of Dead Sea

Fragments from almost every OT book recovered, including scroll containing almost entire text of Isaiah (but no Esther!)

DSS, dating from 1st century B.C., have pushed back textual history of OT 1000 years

Many scrolls closely match Masoretic tradition

Have the DSS Changed Our Modern Translations?

James C. VanderKam, OT professor at Notre Dame, answered the question this way at a Smithsonian Institution symposium in 1990 called “The Dead Sea Scrolls After Forty Years”:

”If you look at any contemporary translations of the Bible into English, you will see in the footnotes a number of references to available Qumran texts and sometimes those readings are included. For the Revised Standard Version, the Old Testament of which came out (I think) in 1952, the translators had access to the Isaiah scroll and included 15 or 17 emendations from the Isaiah scroll in their translation. There are more in the New Revised Standard Version….”

OT Textual Evidence

The Septuagint (LXX)

Greek translation of OT text produced by Jews in Egypt in mid-third century B.C. to allow continued use of scriptures by generations of Jews who knew Greek better than Hebrew

Name comes from Latin word for “seventy,” a rounded-off reference to the 72 scholars who – according to legend – completed their work in 72 days

Significant because it represents pre-Masoretic traditions; most direct OT citations in NT match LXX, not MT (e.g., Matthew 1:23 – Hebrew “young woman’; Greek “virgin”)

Have to “retrovert” (translate back into Hebrew) to use in process of textual criticism

Use of the LXX in Our Modern Translations

From the Preface to the NRSV: “For the Old Testament the Committee has made use of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia…. This is an edition of the Hebrew and Aramaic text as current early in the Christian era and fixed by Jewish scholars (the “Masoretes”)….

“Departures … have been made only where it seems clear that errors in copying had been made before the text was standardized. Most of the corrections adopted are based on the ancient versions (translations into Greek, Aramaic, Syriac, and Latin) which were made prior to the time of the work of the Masoretes and which therefore may reflect earlier forms of the Hebrew text. In such instances a footnote specifies the version or versions from which the correction has been derived and also gives a translation of the Masoretic text….”

NT Textual Evidence

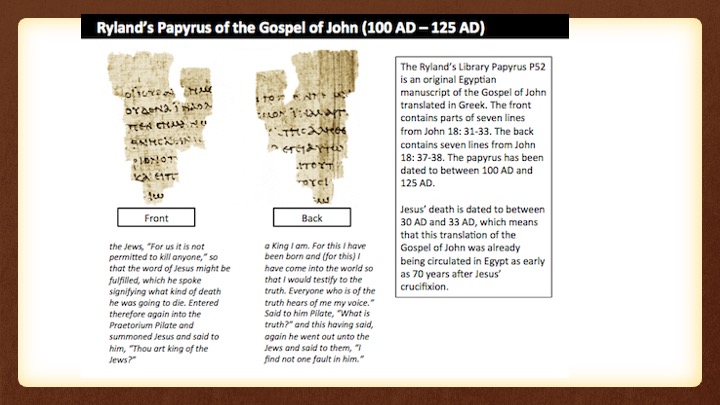

Much greater manuscript evidence for NT – over 5,000 Greek manuscripts (most are fragments - see Rylands Papyrus 52, next slide)

Earliest, most complete texts are three great uncial (written in capital letters) codices, in Greek, from fourth and fifth centuries A.D.: Codex Vaticanus (4th century), Codex Sinaiticus (4th century), and Codex Alexandrinus (5th century)

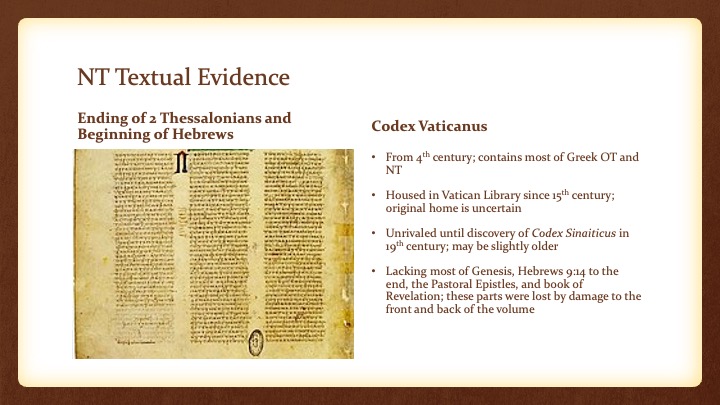

NT Textual Evidence

Codex Vaticanus

From 4th century; contains most of Greek OT and NT

Housed in Vatican Library since 15th century; original home is uncertain

Unrivaled until discovery of Codex Sinaiticus in 19th century; may be slightly older

Lacking most of Genesis, Hebrews 9:14 to the end, the Pastoral Epistles, and book of Revelation; these parts were lost by damage to the front and back of the volume

NT Textual Evidence

Codex Sinaiticus

From 4th century; oldest copy of entire Greek NT; missing some of OT (it’s a long and fascinating story)

Housed in British Library, Leipzig University Library, St. Catherine’s Monastery, Russian National Library (it’s a long and fascinating story)

Found in 1844 at St. Catherine’s Monastery by Constantin von Tischendorf (where the long and fascinating story begins)

Does not contain Mark 16:9-20 (post-resurrection appearances of Jesus) or John 7:53-8:11 (woman caught in adultery)

Codex Sinaiticus:

The Long and Fascinating Story Abbreviated

Leipzig biblical scholar Tischendorf traveled extensively in search of ancient Bible manuscripts

While at Eastern Orthodox monastery at Mt. Sinai, saw ancient-looking manuscript in basket of fire kindling

Had discovered what we now call Codex Sinaiticus; monks figured out something big was up and allowed Tischendorf to take only 43 pages with him (still in Leipzig)

Made a second trip to St. Catherine’s and tried to buy manuscript; was unsuccessful

Codex Sinaiticus:

The Long and Fascinating Story Abbreviated

Made a third trip under patronage of Czar of Russia

Convinced monks to let him borrow manuscript to copy it; gave a promissory note for its return (pictured here); never returned (St. Catherine’s has a dozen sheets later discovered after an earthquake)

Gifted to Czar and placed in Russian National Library

Economic downturn in Russia led to sale of most of manuscript to England where it still resides in British Library

NT Textual Evidence

Codex Alexandrinus

From 5th century; copy of entire OT in Greek (LXX+) and Greek NT

Name (“Book of Alexandria”) derived from city of Alexandria, Egypt; brought to Constantinople in 1621

Greek Orthodox Patriarch in Constantinople had close ties to Britain and Church of England; presented manuscript to Charles I in 1627; now in British Library

Excursus: Where is Emmaus?

Textual Criticism in Aid of Archaeology

Luke 24:13 Now on that same day two of them were going to a village called Emmaus, about seven miles[f] from Jerusalem, 14 and talking with each other about all these things that had happened. 15 While they were talking and discussing, Jesus himself came near and went with them, 16 but their eyes were kept from recognizing him.

f. Greek sixty stadia; other ancient authorities read a hundred sixty stadia

Excursus: Where is Emmaus?

Textual Criticism in Aid of Archaeology

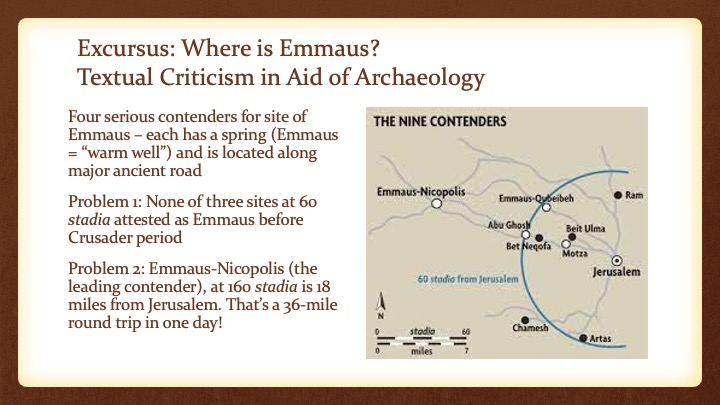

Four serious contenders for site of Emmaus – each has a spring (Emmaus = “warm well”) and is located along major ancient road

Problem 1: None of three sites at 60 stadia attested as Emmaus before Crusader period

Problem 2: Emmaus-Nicopolis (the leading contender), at 160 stadia is 18 miles from Jerusalem. That’s a 36-mile round trip in one day!

Excursus: Where is Emmaus?

Textual Criticism in Aid of Archaeology

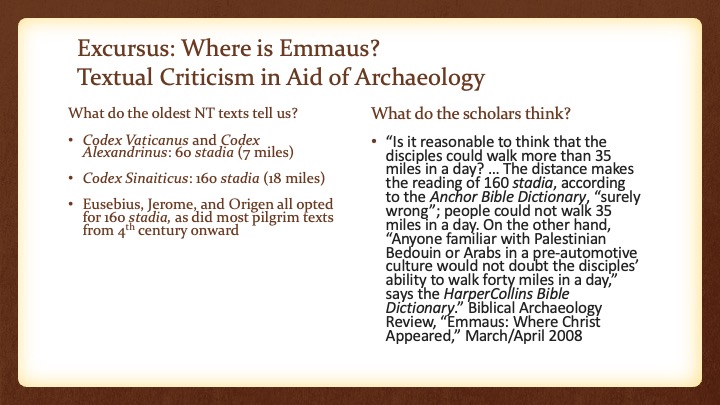

What do the oldest NT texts tell us?

Codex Vaticanus and Codex Alexandrinus: 60 stadia (7 miles)

Codex Sinaiticus: 160 stadia (18 miles)

Eusebius, Jerome, and Origen all opted for 160 stadia, as did most pilgrim texts from 4th century onward

What do the scholars think?

“Is it reasonable to think that the disciples could walk more than 35 miles in a day? … The distance makes the reading of 160 stadia, according to the Anchor Bible Dictionary, “surely wrong”; people could not walk 35 miles in a day. On the other hand, “Anyone familiar with Palestinian Bedouin or Arabs in a pre-automotive culture would not doubt the disciples’ ability to walk forty miles in a day,” says the HarperCollins Bible Dictionary.” Biblical Archaeology Review, “Emmaus: Where Christ Appeared,” March/April 2008

Christian History Interview with Bruce Metzger

We have about 5,000 Greek manuscripts that contain at least a portion of the New Testament, but in many places, they do not agree exactly on wording. And most of the earliest copies are 100 to 200 years later than the originals. From a historical perspective, how accurately does the modern Bible reflect the content of the original manuscripts?

To answer this question, Christian History talked with Bruce Metzger, professor emeritus of Princeton Theological Seminary. Dr. Metzger has had a distinguished career in biblical studies. His most important work was heading the translation committee for the New Revised Standard Version (1990).

How We Got Our Bible: Christian History Interview — From the Apostles To You

Note: the following article, copied from Christian History magazine, is an interview with noted bible historian Bruce Metzger, professor emeritus of Princeton Theological Seminary. It can give us a unique perspective on this question of how reliable our current bible is.

We have about 5,000 Greek manuscripts that contain at least a portion of

the New Testament, but in many places, they do not agree exactly on wording.

And most of the earliest copies are 100 to 200 years later than the originals.

From a historical perspective, how accurately does the modern Bible reflect the

content of the original manuscripts?

To answer this question, Christian History talked with Bruce Metzger, professor emeritus of Princeton Theological Seminary. Dr. Metzger has had a distinguished career in biblical studies. His most important work was heading the translation committee for the New Revised Standard Version (1990).

The interview has questions asked by "Christian History" and answered by "Bruce Metzger".

The Interview

Christian History: For most of its long history, the Bible was copied by hand. How easy was it for a mistake to enter into this process?

Bruce Metzger: Whenever something is copied by hand, frailties of human eyesight enter in, particularly if that document is old and some ink has faded. Copying is also long, tedious work. It would take a scribe several months to copy just one Gospel. In some secular Greek manuscripts, scribes left a note at the end that indicates the patient labor involved: “As the traveler rejoices to see the home country, so the scribe rejoices to see the end of a manuscript!” The invention of eyeglasses around 1375 certainly helped reduce the number of mistakes. And the invention of printing with movable type in 1456 assured production of duplicate copies. But prior to that, for over a thousand years, everything was done by hand, and the more times an ancient text was copied, the more chance for errors to creep in.

Christian History: How reliable are the Greek and Hebrew manuscripts we have today?

Bruce Metzger: The earlier copies are generally closer to the wording of the originals. The translators of the 1611 King James Bible, for instance, used Greek and Hebrew manuscripts from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Today Bible translators have access to Greek manuscripts from the third and fourth centuries and Hebrew manuscripts from the era of Jesus. We even have the Rylands Papyrus, just a torn page with a few verses from John 18, that we can date between a.d. 100 and 150. So today we have access to a text of the Old and New Testaments that is more basic, more fundamental, less open to charges of scribal error or change.

Christian History: How can we date such manuscripts accurately?

Bruce Metzger: Since manuscripts rarely have dates on them, we must judge the date by the handwriting. Handwriting styles differ with the times. So we compare the handwriting of a manuscript with that of deeds and bills of sale and other documents that do include dates. In addition, sometimes a scribal note in the margin or on the dedication page gives away the period in which the manuscript was copied.

Christian History: Most of the earliest surviving New Testament manuscripts are 100 to 200 years later than the originals. Is that cause for concern?

Bruce Metzger: By contrast, our copies of other ancient writings, like those of Virgil or Homer, are often many hundreds of years later than their originals. In some of those writings, we have only one copy! The New Testament, on the other hand, has many copies.

Christian History: Over the centuries of transmission, have scribal errors touched any core Christian doctrines?

Bruce Metzger: No key doctrine of the Christian faith has been invalidated by textual uncertainty. On the other hand, some passages have been affected. For example, take Mark 9:29. Jesus is explaining how he was able to cast out a demon, and in the earliest manuscripts, he is quoted as saying, “This kind can come out only by prayer.” In the Greek manuscripts the KJV translators used, the two words and fasting are tacked on. I do not think that is an earth-shaking difference, but it is typical of the kind of changes we are talking about.

Christian History: How would such a change have taken place?

Bruce Metzger: By studying manuscript history, we see that the words and fasting were inserted between 300 and 600. These were the years of the desert fathers and the birth of monasticism. The number of official fast days was increasing, and the regimens of fasting were becoming more strict. Probably a devout scribe, himself part of a fasting tradition, believed that Jesus must have meant to include “and fasting,” so he included the two words.

Christian History: Some Bibles list three endings for the Gospel of Mark. How should we understand these?

Bruce Metzger: The earliest Greek, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, and Latin manuscripts end the Gospel of Mark at 16:8: “The women said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.” That does not sound like an appropriate ending for a book of good news, so some early scribes, undertaking their own research, added what they thought would be appropriate endings. A few later manuscripts add just two or three verses to this abrupt ending, but most contain a longer ending, what we now number as verses 9 to 20. We can tell by examining the vocabulary that these endings were not written by Mark. So translators often put them in brackets or as a long footnote.

Christian History: Why not just keep them out of the Bible?

Bruce Metzger: Many translators, including myself, consider verses 9 through 20 to be a legitimate part of the New Testament. In the third and fourth centuries, when church fathers were deciding which books should be included in the New Testament, these verses were already in the copies of Mark that most of them were using. In other words, the early church considered verses 9 through 20 to be a credible account of the Resurrection. Though these verses were not written by Mark, I believe we have here a fifth evangelical witness to the resurrection of Jesus.

Christian History: You mentioned Coptic, Armenian, and Latin manuscripts—It sounds as though the Bible was being rapidly translated from the beginning.

Bruce Metzger: Not really. By the year 600, the Gospels had been translated into only eight languages. By the time of the Reformation, there were Bibles or portions of it translated into only 33 languages—out of a total of about 6,000 languages! It is discouraging to see how slow the church was in providing translations of the Holy Scriptures.

Christian History: When did that change?

Bruce Metzger: Not until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with the expansion of the Protestant missionary movement. According to the American Bible Society, at the end of 1993, the entire Bible has been translated into 329 languages, and at least one book of it has been translated into 2,009 languages. That means, of course, that a good many languages still lack even one book of the Bible. On the other hand, since 85 percent of the world speaks one of these 2,009 languages, the vast majority of people have access to at least one book. The Wycliffe Bible Translators and others have done wonderful work in reducing many languages to written form and then translating the Bible into them.

Christian History: In terms of the English Bible, it seems that the last few decades have been extraordinary years of translation.

Bruce Metzger: Between 1952, when the Revised Standard Version came out, and 1990, when the New RSV came out, there were 27 complete translations of the Bible in English published, plus another 25 New Testament translations - all within 38 years. That is unprecedented in the history of translation. Part of this activity is related to manuscript discoveries; when we discover still more ancient biblical manuscripts or ancient secular manuscripts that shed light on ancient languages, people naturally want that information reflected in their Bibles. Also, many different religious groups—Roman Catholics, moderate and conservative Protestants, and Jews—have each wanted their own translations. In addition, there is the economic factor: the Bible is a bestseller, so many publishing companies have been inclined to sponsor and publish new versions.

Christian History: With so many Bible translations available, are English-speaking people more biblically literate than in the past?

Bruce Metzger: I am not sure. In the first 1,500 years of the church’s history, literacy was low, and there were not many copies of the Scriptures available to read. Of the 5,000 Greek manuscripts of the New Testament now available, only 59 have all 27 books. That means that few congregations, and far fewer individuals, had access to all of the New Testament, let alone the whole Bible. Today we live in a culture of relatively high literacy, but we also have many, many newspapers, magazines, and books to read. In addition, radio, television, and the movies are a major distraction from reading. In some ways, then, people who can read probably are not as familiar with the Bible as those who could read in previous eras.

Christian History: You’ve spent the bulk of your 80 years immersed in this one Book. What has kept you energized?

Bruce Metzger: The very fact that the Bible is inspired to be Holy Scripture. I read it, and I am inspired by the inspired words of the writers. I also find it interesting as literature. It is productive for life, for the church, for the individual believer. I thank God that I am still able to study its passages. As long as I am able, I want to follow the motto that is found in a 1734 edition of the Greek New Testament: “Apply yourself totally to the text; apply the text totally to yourself.”

By Bruce Metzger