Examining the New Testament Lesson 3

Examining the New Testament - Lesson 3

Examining the New Testament Lesson 3

Links

< Home Page> < Examining N.T. Menu > < Top of Page >

A Panoramic View

of the New Testament

(In Three Weeks)

Today is Week 3

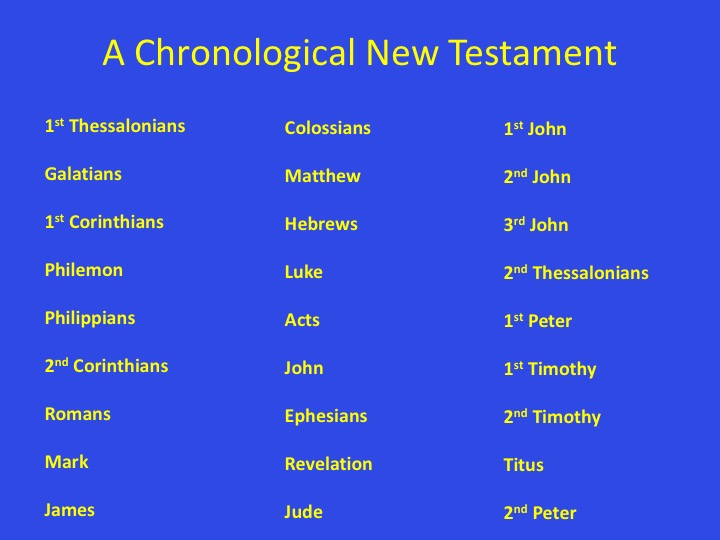

A Chronological New Testament

1st Thessalonians Galatians 1st Corinthians

Philemon Philippians 2nd Corinthians

Romans Mark James

Colossians Matthew Hebrews

Luke Acts John

Ephesians Revelation Jude

1st John 2nd John 3rd John

2nd Thessalonians 1st Peter 1st Timothy

2nd Timothy Titus 2nd Peter

We begin with Mark

MARK

• Around the year 70, an early Christian put the story of Jesus into written form for the first time. Though the location is uncertain, the best guess is a Christ-community near the northern border of Galilee in the Jewish homeland.

• Mark is also the shortest gospel. It has sixteen chapters, compared to Matthew’s twenty-eight, Luke’s twenty-four, and John’s twenty-one. It is important though as the gospels of Matthew and Luke clearly later used Mark when they wrote.

MARK’S STORY

• It is challenging to read Mark as the first gospel—as if the other gospels didn’t exist and this is our first encounter with the story of Jesus. It requires imagining that we haven’t already heard about Jesus from the other gospels, from Christian preaching and teaching, and from what is taken for granted about Jesus in Christian and popular culture.

• Mark’s story is striking because of what it does include and what it does not include.

• There are no stories of Jesus’s birth or early years. It begins with Jesus as an adult.

• The large collection of teachings shared by Matthew and Luke and commonly assigned to Q do not appear in Mark.

• Many of Jesus’s best-known parables are not in Mark.

• In Mark Jesus never publicly proclaims his identity.

• Mark has no stories of the risen Jesus appearing

MARK’S EASTER SUNDAY

• Mark’s description of Easter Sunday is remarkable for it’s brevity. It is eight verses.

• Three women go to the tomb to anoint Jesus with spices. They walk into the tomb and are greeted by a young man in a white robe who announces, “Fear not”, Jesus was crucified, he has been raised, he is not here.” An incredibly concise summary of a world changing event.

• Then the white-robed figure promises that the women and Jesus’s other followers will see Jesus in Galilee: “There you will see him, just as he told you” (16.7).

• Mark could have ended his Gospel right there but he chose to add one more verse. It said that “the women fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them, and they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.” Mark 16.8)

• As you can probably imagine, Mark’s ending has been puzzling for a long time, beginning in Christian antiquity. New endings were added in the early centuries of Christianity, one from the late second century and another one from the fourth century.

• But modern Bible scholarship has devoted considerable attention to Mark in trying to understand why it ended so abruptly.

• But interestingly one view often expressed is in admiration of Mark’s abrupt and concise way of communicating. They believe it unambiguously proclaims the central conviction of Jesus’s followers post Easter. As one scholar noted Mark expressed what they all realized with great economy and it’s all there. “Jesus was crucified - the tomb is empty – Jesus is loose in the world – the Kingdom of God has arrived.”

James

• For centuries, Christian tradition took it for granted that the author was James, the brother of Jesus.

• But the majority of mainstream scholars do not think the author was the brother of Jesus. The author does not say so, but describes himself simply as “James, a servant of God and of the Lord Jesus Christ.” And his use of Greek language and grammar is quite sophisticated—not impossible for a brother of Jesus from the peasant class whose native language was Aramaic, but at least unlikely.

• There is little in this document that is overtly theological, nothing about the death and resurrection of Jesus, nothing about “doctrines” that are to be believed. Its focus is primarily practical, combining wisdom about how to live and prophetic indictment of how people commonly do live.

•The author emphasizes the importance of doing and acting. Two of the best-known passages are: “Be doers of the word, and not merely hearers…doers who act” (1.22–25) and “Faith without works is dead” (2.14–26). His examples of “works” are concretely compassionate: clothing the naked, feeding the hungry, supplying their bodily needs.

• “Wisdom”—how to live - is a frequent theme in James. And he (like Jesus) includes harsh indictments of the rich and their position in the world.

Colossians

• Colossians is almost certainly the earliest of the letters attributed to Paul but probably not written by him.

• In style and content, it differs significantly from the first seven letters of Paul. Its sentences are much longer and more complex. Its content not only goes beyond what is in the first seven letters, but sometimes conflicts with them.

• The earliest New Testament example of what are called “household codes” begins in Colossians. It includes the subordination of wives to husbands and slaves to masters. “Wives, be subject to your husbands, as is fitting in the Lord” (3.18). Slaves are to be obedient to their “earthly masters in everything, not only while being watched and in order to please them, but wholeheartedly, fearing the Lord” (3.22).

• The radicalism of Paul’s early communities (and in the life of Jesus) is beginning to be accommodated to the hierarchical normalcy of the Roman world.

Colossians Content

• I would like to mention a very striking passage where Colossians describes the “cosmic Christ” in saying what is seen in Jesus is:

•”the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him. He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together. He is the head of the body, the church; he is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead, so that he might come to have first place in everything. For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven.” (1.15–20)

Matthew

• Matthew was written a decade or two after Mark, in the 80s or perhaps early 90s.

• In an important sense, Matthew is an expanded version of Mark.

• Matthew used 90 percent of Mark (about 600 of Mark’s 678 verses) in his 1,071 verses. To Mark he added birth stories (48 verses) and about 400 verses mostly of Jesus’s teaching. About 200 of those come from Q, the collection of Jesus’s teaching shared with Luke.

The Structure

• Though Matthew takes over Mark’s threefold narrative pattern of Galilee, journey to Jerusalem, and Jerusalem, he also imposes his own fivefold structure. In between the stories of Jesus’s birth in chapters 1–2 and his final days in 26–28, the body of Matthew’s gospel has five “blocks” or “sections” of material, as scholars have long noted.

• Matthew’s fivefold structure and the theme it expresses indicate the gospel’s deep roots within Judaism. Of course, the other gospels and the New Testament are also rooted in Judaism, but Matthew emphasizes this more.

• Matthew quotes the Jewish Bible forty times with an explicit phrase such as “It is written” and another twenty-one times without such a phrase. Only Matthew affirms the eternal validity of the “law” and the “prophets.”

• Jesus says in this gospel (and only in this gospel): “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfill. For truly I tell you, until heaven and earth pass away, not one letter, not one stroke of a letter, will pass from the law until all is accomplished” (5.17–18).

Matthew – Affirmation & Hostility

• Yet Matthew is deeply hostile toward “Jews”—meaning those who opposed Jesus or did not respond to him.

• The hostility dominates a whole chapter in Matthew’s story of Jesus’s final week in Jerusalem. Matthew 23, added to the story of Jesus’s last week as told by Mark, is a sustained indictment of the “scribes and Pharisees.”

• Though some of the content of Matthew’s indictment of scribes and Pharisees is also found in Luke (and is thus from Q), Matthew’s language is stridently condemnatory and includes name-calling. They are not just hypocrites, but children of hell, “blind guides,” “blind fools.” They are “whitewashed tombs” that look great outside, but are filled with rot and death inside. They are “snakes,” a “brood of vipers,” and “descendants of those who murdered the prophets.”

• Finally, in Matthew, Jesus restricts his mission during his lifetime to Jews. When he gives his disciples mission instructions, he tells them: “Go nowhere among the Gentiles, and enter no town of the Samaritans, but go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (10.5–6).

• Later he says about himself: “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (15.24). It is only the risen Jesus, the post-Easter Jesus, in the last verse of the gospel, who commissions his followers to go to “the nations” (the Gentiles).

Hostility – Historical Contextualization

• Matthew wrote during a time of growing conflict between Christian Jews and non-Christian Jews in the last decades of the first century.

• The conflict was particularly intense in and near the Jewish homeland, where there were large Jewish communities.

• One reason was the growing number of Gentile Christians, especially outside of the homeland. Though Gentiles were still a minority of Christians and would remain so for perhaps another century or so, early Christian communities increasingly included Gentiles who had not become Jews. The men remained uncircumcised, and adherence to Jewish food and purity laws was not required.

• The conflict led to what has been called “Jewish persecution of Christians.” It began in the decades around the time Matthew wrote. Compared to later Christian persecution of Jews, it was mild and seldom lethal.

• Rather, Jewish persecution of Christian Jews in the decades after 70 took the form of social ostracism. Commonly called “expulsion from the synagogue,” it was far more serious than being expelled from a church today.

• To be expelled from the synagogue, “the gathering” or “assembly,” which is what the word meant, resulted in exclusion from the Jewish community.

• Though we do not know the details of what this included, presumably it meant no marriage between Christian Jews and non-Christian Jews and perhaps the severing of family and economic relationships. In locations where Jews were the majority of the population, the consequences could have been severe.

The Ending of This Gospel

• Recall that Mark’s gospel ends with the story of an angel promising the women at the empty tomb that Jesus would appear to his followers in Galilee, though no appearance is narrated. In his last chapter, Matthew adds a story of Jesus appearing to his disciples in Galilee, thereby fulfilling the promise in Mark.

• In the final words of the gospel, the Jesus of Matthew promises his followers: “Remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.” The ending returns to a theme announced at the beginning of Matthew’s gospel. In his story of Jesus’s birth, he names Jesus as “Emmanuel” (citing Isa. 7.14) and explains that it means “God is with us” (1.23). Now the risen Christ says the same thing about himself in first-person language: “I am with you always.”

Hebrews

• The document we know as “the letter to the Hebrews” is exceptionally rich. Its central and best-known metaphor presents Jesus as the “great high priest” who offers himself as the “once for all” sacrifice. Its chapter on faith is one of the most famous in the New Testament. Its creative use of texts from the Jewish Bible, especially from Psalms and the prophets, is powerful.

• We do not know who wrote it. Origen, in the 2nd century declared the author was only known to God.

• From the document itself, we learn a few things about the author. His use of Greek and his literary style were very sophisticated, perhaps the best in the New Testament. He knew the Old Testament very well, quoting it thirty times, sometimes at considerable length, and alluding to it another seventy times. He was brilliant, creatively weaving together evocative readings of texts from the Jewish Bible with a presentation of Jesus as the Son of God, who is also the great high priest and sacrifice.

• Hebrews begins: “Long ago,” God spoke to our ancestors in many and various ways by the prophets, but in these last days…has spoken to us by a Son.” God has appointed him “heir of all things,” and through him God “also created the worlds.” He is no less than “the reflection of God’s glory and the exact imprint of God’s very being,…he sustains all things by his powerful words,” and he is now “at the right hand of the Majesty on high” (1.1–3).

• These affirmations about Jesus are like those in Colossians and the gospel of John, both of which speak of the cosmic Christ present with God at creation.

Luke – Acts

•We combine these because they had the same author, and Acts continues the story.

•Luke used Mark as a major source, as did Matthew, but in a different way. He has the same threefold narrative pattern of Mark (teaching in Galilee, the journey to Jerusalem, then the passion story in Jerusalem). But he expands the journey section from 3 chapters to 9 chapters, and has major teaching elements in that journey.

•With respect to the birth stories of Jesus, they are very different than Matthew’s. There is no mention of Herod’s plot, no star of Bethlehem, no wise men, and no flight into Egypt. In Luke, Mary is the main character, not Joseph, as in Matthew. There are more differences. In Matthew, the holy family lives in Bethlehem, and Jesus is born at home. In Luke, they live in Nazareth, and Jesus is born in a stable in Bethlehem.

•Matthew’s story is dark and full of foreboding, dominated by Herod’s attempt to kill Jesus. Luke’s is full of joy. Three “hymns,” known by Christians ever since as the Benedictus, the Magnificat, and the Nunc Dimittis, herald the coming of Jesus. Angels sing in the night sky to shepherds, “Glory to God in the highest.”

•The final hymn, the Nunc Dimittis, ends with an affirmation of the significance of Jesus not only for Jews, but also for Gentiles; he is the “salvation” that God has “prepared in the presence of all peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles” (2.30–32; Yet the very last line of the Nunc Dimittis reads: “and for glory to your people Israel.”

•The author proclaims in both volumes that the inclusion of Gentiles as well as Jews in the Jesus movement was divinely and providentially ordained from the beginning of Jesus’s life. It was neither an accident nor a mistake.

John

• The gospel of John is very different from the synoptic gospels, as we will see. And yet its language has shaped Christian understandings of Jesus and his significance perhaps even more than the first three gospels. Its language is both familiar and beloved by many Christians:

• Its use of archetypal imagery to testify to the significance of Jesus is magnificent and powerful. For millions of Christians ever since, Jesus has been “the Word” become flesh, the Light of the World, the Bread of Life, the Way, the Truth, and the Life. Much of John’s language speaks to the deepest of human yearnings. In the gospel’s final scene, the post-Easter Jesus speaks words that are also central to the synoptics: “Follow me” (21.19). Follow Jesus; he is the word and wisdom of God incarnate, the light, the bread that satisfies our hunger, the way, the truth, and the life. Jesus is the embodiment of what can be seen of God in a human life; so follow him.

Ephesians

• Like Colossians, Ephesians is one of the “disputed” letters of Paul. A minority of modern scholars argue that it was written by Paul, but a majority have concluded that it was written a generation or so after Paul’s death. Though it has the typical form of a Pauline letter and echoes some important themes from the seven genuine letters of Paul, it also differs in several ways.

• The differences include style and subject matter. In Ephesians, as in Colossians, many of the sentences are very long, unlike the commonly short and energized sentences of Paul’s genuine letters.

• Differences in subject matter include the emphasis of Ephesians on its extended “household codes,” about which more will be said later.

• Despite the fact that Ephesians not only goes beyond and sometimes seems to compromise Paul’s teachings in his seven genuine letters, the letter also echoes some of what was central to some of Paul’s theology. For example, 2.7–10 concisely summarizes Paul’s affirmation of justification by grace through faith, found in Galatians and Romans. The author proclaims:

• 2.7-10…”the immeasurable riches of [God’s] grace in kindness toward us in Christ Jesus. For by grace you have been saved through faith, and this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God -not the result of works, so that no one may boast. For we are what [God] has made us, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand to be our way of life.”

• Ephesians also includes “rules,” or directives, for the structuring of Christian life. The “household code” for Christians that appears for the first time in nine verses in Colossians (3.18–4.1) is expanded in Ephesians (5.21–6.9) to twenty-two verses. Some of these rules relate to husbands and wives in marriage.

• ”Wives, be subject to your husbands as you are to the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife just as Christ is the head of the church, the body of which he is the Savior. Just as the church is subject to Christ, so also wives ought to be, in everything, to their husbands. Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ loved the church.” (5.22–25)

Ephesians – Slaves & Masters

• The household code concludes with the relationship between slaves and masters:

• ”Slaves, obey your earthly masters with fear and trembling, in singleness of heart, as you obey Christ; not only while being watched, and in order to please them, but as slaves of Christ, doing the will of God from the heart. Render service with enthusiasm, as to the Lord and not to men and women, knowing that whatever good we do, we will receive the same again from the Lord, whether we are slaves or free.” (6.5–8)

• This position is very different from the one espoused by Paul in Galatians and Philemon.

Revelation

• So how do we explain Revelation.

• It describes the second coming of Jesus, the ending of “this world,” and its replacement by a new heaven and a new earth. Its final two chapters describe the “new Jerusalem” descending to earth, a glorious city in which mourning, crying, pain, and death are no more.

• Because Revelation speaks about the second coming of Jesus and the events preceding it, many Christians throughout the centuries have convinced themselves that it refers to events that are still in their future, because to say the obvious, the second coming of Jesus hasn’t happened. Therefore, what Revelation speaks about must still be in the future, and it could be soon.

• A recent poll suggests that as many as 40 percent of American Protestants think it certainly or probably will happen by the year 2050, a conviction based on the futurist interpretation of Revelation.

• A historical contextualization sets Revelation in its late first-century context and asks what it meant (past tense) then. What did its language mean to its author and to the early Christian communities to which it was addressed? Within their shared field of meaning, what did he communicate to them?

• The answers that result are fairly clear.

• Seven times he writes, “The time is near,” “what must soon take place,” “I am coming soon.” “Soon” and “near” cannot plausibly be extended to two thousand years and counting. Like the authors of a number of New Testament documents, John of Patmos thought the second coming would happen soon.

Revelation – The Symbolism

• The author identified the dragon, the ancient serpent, Babylon the Great, the great whore, the beast whose number is 666. It was Rome—not just the city, but the Roman Empire. The identification is unmistakable in a late first-century context.

• Because of the Roman destruction of Jerusalem in 70, Jews and Christians spoke of Rome as “Babylon”—because the Babylonian Empire was the previous destroyer of the holy city and its temple. The woman and the beast live in a city built on seven hills, a designation for Rome that goes back to antiquity.

• It is the city that rules the world; in a first-century context, that could only be Rome. The number 666 is a numerical code for Caesar Nero, the first Roman persecutor of Christians. The beast is the Roman Empire of the first century—not some future beast from our point in time.

Jude

• Jude is perhaps the strangest document in the New Testament. It is one of the shortest, about a page long, and is the most enigmatic. Its authorship, the community to which it was addressed, and its date involve more “guesswork” than any other document.

• It was taken for granted until recently that Jude was a brother of Jesus.

• If so, that would make Jude one of the earliest documents in the New Testament. But modern mainline scholars have concluded that it was written much later. Though precision is impossible, most date it around 100.

• Finally, it is the most judgmental and condemnatory of all the New Testament documents. Of course, these themes are found in other places in the New Testament, but even Revelation is not as consistently judgmental and condemnatory.

The Johns I-II-III

•Three letters are attributed to “John” in the New Testament. The first is the most substantial and important. Five chapters long, it emphasizes love as much as any document in the New Testament. The other two are less than a page long and are among the shortest documents in Christian scripture.

•John I has been associated with the Gospel of John since the 2nd century because they share so many themes.

•John II is only 13 verses. It is a letter addressed to the “elect lady and her children”. We don’t know who this lady is.

•John III is also very brief. Addressed to some one named Gaius.

2 Thessalonians

•Paul’s first letter to the Christ-community in Thessalonica in northern Greece is the earliest document in the New Testament, but 2 Thessalonians is one of the disputed letters of Paul. The majority of mainstream scholars do not think it was written by Paul, but by someone writing in his name some three to four decades after his martyrdom in the 60s.

•The letter addresses two questions that belong to a time period later than Paul: the delay of the second coming of Jesus and the issue of “freeloaders”—people who became part of a Christ-community in order to receive free food.

•Recall that Paul in 1 Thessalonians expected it soon. But this letter affirms that there are events that must happen first: and mentions a "rebellion,” and the revelation of the “lawless one”. Though the recipients of the letter most likely understood what the author was writing about, we do not.

1 Peter

•Two letters in the New Testament have been attributed to Peter. But today the majority of mainstream scholars do not think that either one was written by Peter. The letters reflect a later historical context. Moreover, they were not written by the same person. Second Peter is significantly later than 1 Peter. 1 Peter is thought to have been written around 90 AD.

•The letter is addressed to Christ-communities in five regions of Asia Minor (Turkey). It was thus a “circular” letter, carried and read to several communities in different locations.

•The letter indicates that these communities were mostly made up of Gentile followers of Christ.

•The letter combines affirmations about Jesus, God, and the new life with exhortations, moral teaching, and encouragement. The rhythm is repeated again and again.

•But some of these affirmations seem to reflect a later accommodation to the dominant culture.

•Verses 2.13 – 3.7 is an extended passage urging obeying worldly authority.

•The recipients are to “accept the authority of every human institution,” including the emperor and governors. Slaves are to accept the authority of their masters, and wives, the authority of their husbands. This teaching about slaves and wives is also found in Colossians, Ephesians, and 1 Timothy, documents from the last part of the first century and early second century.

•It also uses the language of being “born again”, which only occurs in John.

Martin Luther is said to have loved some of the language of this letter. Particularly the language that inspired his notions of a priesthood of all believers. As well as the notion of being living stones. One of those well know passages was in (2.9)

(2.9) “But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people, in order that you may proclaim the mighty acts of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light.”

(2. 4-5) 4 Now you are coming to him as to a living stone. Even though this stone was rejected by humans, from God’s perspective it is chosen, valuable. 5 You yourselves are being built like living stones into a spiritual temple. You are being made into a holy priesthood to offer up spiritual sacrifices that are acceptable to God through Jesus Christ.”

The Pastorals

•1st & 2nd Timothy and Titus are known as the Pastoral letters. Timothy and Titus were associates of Paul mentioned in about 5 of his epistles. They are placed very late in this chronological NT because all evidence indicates they were written much later and their vocabulary, tone, and style as well as some of the most negative comments on issues such as women and slaves in the church were very different than anything Paul wrote in his first 7 letters. Some examples:

•Let a woman learn in silence with full submission. I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over a man; she is to keep silent.

•Let all who are under the yoke of slavery regard their masters as worthy of all honor, so that the name of God and the teaching may not be blasphemed. Those who have believing masters must not be disrespectful to them on the ground that they are members of the church; rather they must serve them all the more, since those who benefit by their service are believers and beloved. (6.1–2)

2 Peter

•There is a strong scholarly consensus that 2 Peter is the last New Testament document to be written. Some date it as late as 150, and most date it between 120 and 150.

•The final chapter of the letter explains why the second coming of Jesus had not yet happened. Recall that many early Christians shared the conviction that it was imminent, close at hand. The author refers to “scoffers” who will ask, “Where is the promise of his coming?” Already their ancestors had died (once again suggesting a late date for the letter), but still the world continued as it was (3.4).

•The author offers a twofold explanation for the delay. First, God’s time is not like our sense of time: “With the Lord one day is like a thousand years, and a thousand years are like one day” (3.8). Second, because of God’s patience, God is providing more time for “all to come to repentance” (3.9).

•The more general theme of the letter is separation from the ways of the world (1.3–11)

•The antidote—the way of escaping the “corruption that is in the world”—is the power and promises of God, who has given them “everything needed for life and godliness” through Jesus. (1.3–4).

•On this foundation, the author writes: “You must make every effort to support your faith with goodness, and goodness with knowledge, and knowledge with self-control, and self-control with endurance, and endurance with godliness, and godliness with mutual affection, and mutual affection with love”. (1.5–7)

• Thus, like the New Testament as a whole, its last letter emphasizes love as the climactic Christian virtue.

We Did It!