History of Christianity Class 12

Crusades, Universities, Scholastic Theology

Mike Ervin

History of Christianity Class 12

Crusades, Universities, Scholastic Theology

The Crusades

The argument has been made that the 11th through the 13th centuries represent the high water mark of the European civilization called Christendom, shaped by specifically Christian values and institutions.

As much as in the monasteries with their schools and the cathedrals with their chapters, and as much as in the universities that we will talk about in the next lecture, the vibrancy and vision of this Christian society is expressed by the series of military expeditions against the Muslim occupiers of the Holy Land.

Backdrop to the Crusades

The Crusades, part popular movement, part political calculation, part religious fervor, began in 1095 and extended, both literally and symbolically, for centuries.

Like the building projects described in the previous class, the expeditions known as the Crusades expressed a new sense of power and self-confidence in European Christianity.

In the 8th century, Europe as a whole had barely escaped coming under Muslim rule during the great expansion of Islam that had swallowed all of the East (except Byzantium), North Africa, and Spain.

Charles Martel had stopped the advance of Muslim armies at the Battle of Tours in 732. His victory was the foundation, as we have seen, of the Frankish kingdom, the prominence of the papacy, and the feudal system that structured medieval society.

In the 11th century, the time seemed right for payback, to reverse the conquests of Islam and take back at least the places that Christians regarded as especially holy and worthy of pilgrimage.

Further, some outlet was needed to channel the aggressive militarism of the ascendant Normans.

The Normans were descendants of the Vikings who settled on the western coast of France; the duchy of Normandy dates from 10th century.

The Norman leader Robert Guiscard had already conquered the Saracens (Muslims) in Sicily and Malta—with the pope’s blessing, and in 1038–1040, we find Normans serving as mercenaries in the Byzantine army. The Normans were great warriors and were spoiling for a fight.

Another strong incentive to undertake a military expedition was the loss of the eastern frontier of the Byzantine Empire to the Seljuk Turks (who were Muslims) in 1071, which threatened not only Byzantium but potentially also the West.

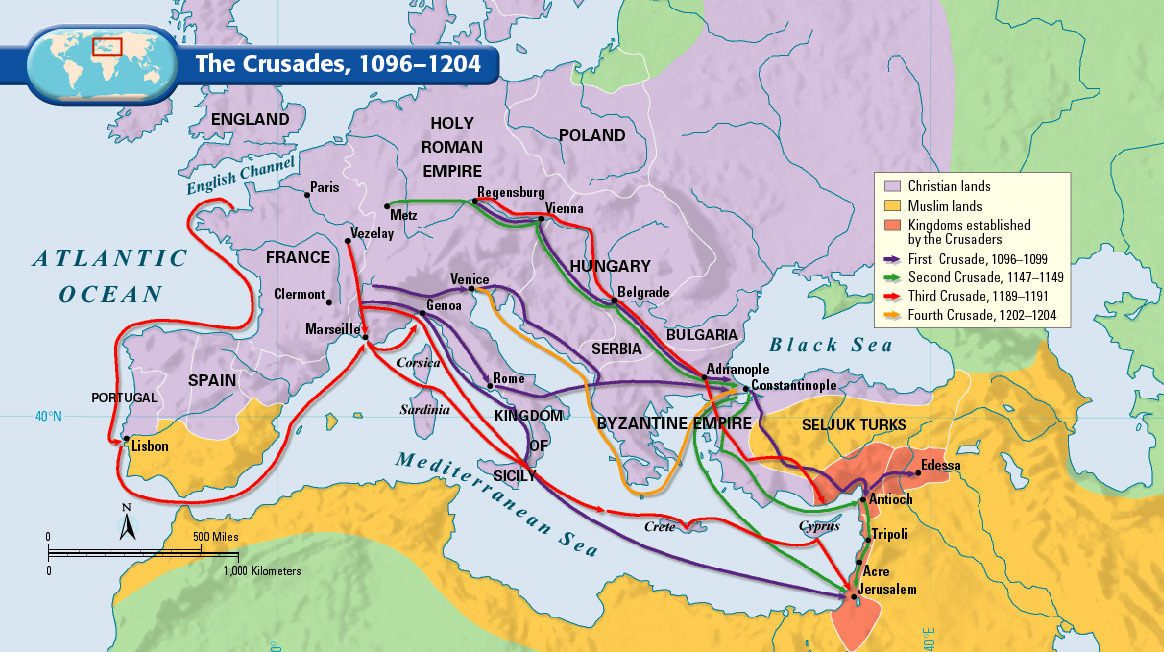

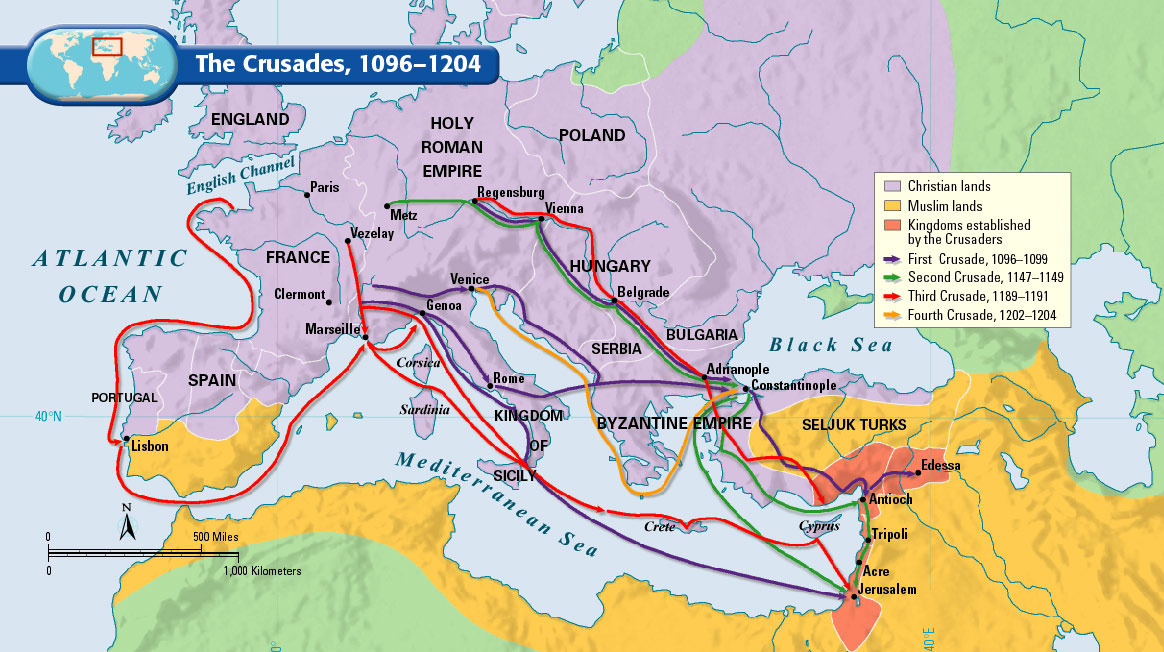

This is an excellent map showing the tracks for the principal four crusades. But for now I want to focus on the lands involved.

Most of the purple in the north is the Holy Roman Empire and predominately Christian. All of the yellow is the areas conquered by the Muslims in the 7th century. That 7th century campaign was led by Muslims predominately out of Arabia. But of particular note is this area now identified as the Seljuk Turks.

These Seljuk Turks are not middle easterners, not Arabia, not even Persian. You recall the mass migration of German tribes that engulfed western Europe earlier. In roughly the 10th century another great migration was moving into the old Persian empire. They were the powerful Seljuk Turks, the namesakes of modern Turkey. Their homeland was actually in western Mongolia. As they began to arrive they converted to Islam and soon in rather short order took control of much of Anatolia, the eastern end of Asia Minor, and all the way down to Jerusalem.

The emperor of the Christian east in Constantinople was very worried that the Turks fully intended to keep moving to the northwest to capture the Eastern Catholic Empire (Constantinople). That assumption by the Emperor was actually a strategic error of rather monumental proportions. We now know from some of the historical records of the Seljuk Turks that they actually had no immediate interest in ither Constantinople or the rest of western Europe. The Seljuk Turks, who were Sunni Muslims instead were completely focused on ridding Islam of the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt. The Fatimids were named after Fatima (daughter of Mohammed) and were Shia Muslims.

So the Emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire assembled a large army of 40,000 men and crossed into Asia Minor to attack the Seljuk Turks before they got any stronger. The result was a disaster. The Turks completely routed the Christian army, surrounded it, and captured the Roman Emperor. This was the Battle of Manzikert. After humiliating the Emperor and extracting a large ransom of gold the Turkish leader sent him home.

Over the next decade the defeated emperor struggled with internal civil wars in his empire, and became more concerned about the Turks. He finally sent a desperate plea to the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor for military aid. This request led to the first Crusade.

The Crusades - Religious Incentives

The papacy promised protection of property for participants, granted plenary indulgences, and promised to regard those who fell in battle as martyrs.

Indulgences were a feature of medieval Christianity that made sense only within the framework of a highly evolved view of the afterlife.

Indulgences were, in effect, “time off” from such punishment; plenary indulgences represented a “full pardon.” Therefore, participation in the Crusades could mean, even if one survived, a direct ticket to heavenly bliss.

History of Christianity

The Crusades - Christian?

There is no question that many of the crusaders were men of genuine piety who accepted generously the cost of such expeditions: separation from home and family and the possibility of suffering and death for the sake of an ideal of no benefit to them personally.

Yet the idea of a holy war was certainly—however much it had become familiar over the centuries—a corruption of original Christian ideals, which advocated peace and the acceptance of violence toward the self rather than its imposition on others.

Not all crusaders had purely religious motives, especially not those most responsible for the missions. Some were probably avid for political and economic gain through booty and through access to lucrative trade routes, although this motivation was probably not dominant.

Perhaps most problematic was the

equation of “defense of the faith” with the killing of “infidels” (“the

unfaithful”), including both Saracens and Jews, without acknowledgment of them

as humans, much less as people of genuine if different faith in the same God.

As many as seven expeditions going by the name of “Crusades” moved from the west to the east, from the north to the south, between the 11th and 14th centuries. We will review only the first four, because they are religiously and politically the most significant and set the pattern for the others.

The First Crusade

The First Crusade was summoned by Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont on November 27, 1095. He summoned the Christians of Europe to free Jerusalem and to relieve the besieged Byzantine Empire.

The pope’s legate Adhemar, bishop of LePuy, was put in charge, together with Robert of Normandy and Godfrey of Bouillon. The cause was hugely popular, and knights and peasants alike were rallied for the expedition.

The knights were disciplined and kept separate from the peasants, who had no military training. It is among the peasants that the Crusade took on the character of a popular movement. The so-called “People’s Crusade” was an offshoot that was led by the charismatic Peter the Hermit.

Lack of discipline (and ignorance) also led to the outbreak of anti- Jewish attacks in both France and Germany. Such “infidels” were closer to hand and viewed as responsible for the death of Christ. The robbing of Jews and the killing of many was the first outbreak of such violence in centuries and set the pattern for a tragic history in Europe.

The name “Crusade” derives from the cross (crux or crosier) that was worn by soldiers on their way to Palestine to liberate the Holy Lands from their muslim occupiers.

The army of Christian knights crossed the Balkans and Asia Minor, conquering Antioch in 1098 and liberating Jerusalem in 1099. The First Crusade was far and away the most successful of all the expeditions.

Fortified Latin states were established in Jerusalem, Tripoli, Antioch, and Edessa, with subsidiary fiefdoms established in Galilee, Transjordan, Jaffa, and Ascalon. The states lasted from 50 to 100 years.

In Jerusalem in 1099, some knights banded together to provide hospice for pilgrims (the Knights Hospitaller), and in 1119, others vowed to protect pilgrims on their way to the church of the Holy Sepulchre (the Knights Templar). These knights organized themselves along the lines of religious orders, with a commitment to piety.

The areas in red on this map show the fortified Latin states that were established in the Holy Land as a result of the First Crusade. During this time many Christians from western Europe could go on pilgrimage (by sea) and visit Jerusalem.

There were a number of ideas (mostly guesswork) proposed for why the crusaders were so successful on this first crusade. One that may have been true was that at the time of that crusade the Turks had already struck at Egypt and captured it, leaving them spread too thin in the Holy Land around Jerusalem.

The first of the latin states to fall back to the Turks was Edessa. This rather shocking development led to the second Crusade.

History of Christianity

The Second Crusade

The Second Crusade was called by Pope Eugene III in 1147 because of the shocking collapse of the Latin state of Edessa to the Saracens.

The pope enlisted Bernard of Clairvaux, one of the most influential figures in Christendom, to preach the Crusade, which Bernard did through an extended tour.

This Crusade was led by King Louis VII of France and King Conrad III of Germany. Once more, mob action was carried out against Jews across Germany, leading Bernard and other leaders to condemn such action.

The military effort in the East was a failure, except for the 13,000 troops who, carrying out another, more local program—managed to free Lisbon from Muslim control.

The great Kurdish Muslim general Saladin (1138–1192) overran Jerusalem and eliminated the Latin state there in 1187.

The Christians were reduced to occupying the stronghold at Tyre, a humiliating setback.

History of Christianity

The Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was led by three Christian kings of Europe: the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (1122– 1190), Richard I of England (1157–1199), and Philip II of France (1165–1223).

The kings demanded financial support from bishops to finance the Crusade—the “Saladin tithe.”

The crusaders, especially Richard of England, managed to recover territory along the coast from the Saracens, but Jerusalem itself remained in Muslim hands. King Richard negotiated the right of pilgrims to visit Jerusalem.

The Fourth Crusade (1202)

The Fourth Crusade in 1202 was stimulated by Pope Innocent III, who assured the Byzantine emperor Alexius III that he would be safe from crusader attack.

The Crusade was, however, hijacked by the Venetians, the emerging commercial force in Italy that was intensely hostile toward its rival Byzantium, and the crusaders attacked Constantinople in 1203.

The Venetians established in Byzantium a Latin empire ruled by the pretender Alexius IV.

Deep local resentment led to the assassination of Alexius; the crusaders responded by sacking the city and establishing Baldwin of Flanders as the Latin emperor. This Latin version of the Byzantine Empire lasted until 1261.

The Fourth Crusade represented a low point in the collapse of the initial ideal of freeing the Holy Land by pitting parts of the Christian world against each other; the incident only hardened the resentment Eastern Christians felt toward the West. It also weakened Constantinople greatly (many inhabitants left the city) and may have contributed to the eventual fall of the city to the Turks two centuries later.

History of Christianity

Later Crusades

Efforts at mounting and carrying out Crusades continued in the 13th century, but (as with the partly legendary “Children’s Crusade” in 1212), most were exercises in vanity and futility.

The crusader ideal was even more sullied when it was transferred to the efforts of kings and popes to extirpate heretics. Innocent III launched an “Albigensian Crusade” in 1208 to try to dislodge and destroy the dualist heretics in southern France. And in the 13th century, the popes spoke in terms of crusade in their battles against the Hohenstaufen dynasty in Italy.

The Latin states in the Holy Land were slowly overrun, and by 1291, all the remaining Latin holdings on the mainland disappeared. The grand experiment in Christian conquest had failed even in strictly military and political terms, not to mention religious ones.

Universities and Theology

One of the most impressive signs of a mature Christian culture in the High Middle Ages was the development of universities. As we have seen, the desire for higher learning within Christianity was never completely lost, even during the most chaotic periods of life in the West.

Universities, though, were a new invention in the West; they emerged when they did because of the convergence of a number of factors. In a flash, over the span of some 80 years, four great universities were founded in Europe that quickly became important centers of learning and eventually contributed heavily to social change: Bologna in 1119, Paris in 1150, Oxford in 1167, and Cambridge in 1200.

In their first stages, the universities were not the great sprawling campuses and huge dedicated buildings we associate with present- day universities.

Students moved about from one “faculty” or “master” to another in the various monastic and cathedral schools; the growth of colleges with distinct student bodies and faculties came with the establishment of student residence halls as growth in student numbers dictated.

There were no “sciences” in the contemporary sense, thus, no laboratories or physical experimentation. Reading texts, lecturing on texts, and taking notes on lectures and texts made up the essential pedagogy. Students paid masters directly after a lecture and on the basis of its satisfying character.

The curriculum through which students passed began with the study of the seven liberal arts and then moved to the advanced study of either law or theology, the professional schools that prepared leaders for church and state.

The first part of the liberal arts was the trivium, consisting of the three basic arts of grammar, logic, and rhetoric. It is important to note that the textual basis for these arts was entirely Christian: the Bible and other “classics” of the Christian tradition.

The quadrivium was given to the four more advanced arts: arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. Again, these were grounded in lore derived from the classics of Christian history. To the quadrivium should be added philosophy, which was regarded as the necessary entry point into theology.

History of Christianity

Scholastic Theology

In these universities, theology was truly “the queen of the sciences” not only because its knowledge gave preferment in the most important profession, but also because it provided the fullest expression of the medieval conception of reality sub specie aeternitatis (“from the perspective of eternity”).

The subject matter of theology was conceived of primarily in terms of doctrines. Over the course of centuries, the statements of the creeds and of Scripture were collated into collections of “Sentences” (sententiae) that expressed key doctrines, together with the scriptural passages that supported the propositions.

This represented a radically different approach to the learning and reading of Scripture than had obtained in the monasteries and cathedral chapters; there, lectio divina, as we have seen, was a ruminative and meditative reading. But the schools were training professionals who had to be brought up to speed within a short time; thus, Scripture was employed technically as “proof texts” for theological positions.

The four books of Sentences written by Peter Lombard (1100– 1160) provided doctrinal statements and scriptural proofs organized according to the topics of the Trinity, creation and sin, Incarnation and the virtues, and the sacraments and “last things” (death, judgment, heaven, hell). The Sentences became the standard textbook for Catholic theology and the basis for commentary by subsequent masters.

If the substance of Scholastic theology was doctrine contained in propositions or sentences, its life and bite came from the invigoration offered by the challenge of philosophy, specifically that of Aristotle, whose works had been translated from Greek into Arabic by Muslims and from Arabic into Latin.

Aristotle’s teachings (for example, on the human soul and on the relation of God to the world) were less apparently congenial to Christian doctrine than had been those of Plato, whose view of the world had been adjudged compatible with the Bible by Christian thinkers from Justin through Origen to Augustine.

For such masters as Thomas Aquinas, however, the teachings of Ibn Sīnā (Latin, Avicenna) and Ibn Rushd (Latin, Averroës), based in an understanding of Aristotle that emphasized the godless aspect of the Greek sage, had to be engaged by the Catholic faith in the same way that ancient philosophers had to be engaged by the early church fathers if Christian faith was to be considered fully rational in character and reasonable to maintain.

In its medieval manifestation, Scholastic theology had great dynamism because of its employment of dialectic, developed especially by Peter Abelard (1079–1142). His Sic et non (Thus and Not Thus) brought dialectical reasoning to theology as he worked through some 158 apparent contradictions in Christian philosophy and theology.

Scholastic theology continued to dominate in the universities and the church for the next 500 years, although not without controversy.

History of Christianity

Scholastic Theology – So What was Controversial?

This scholastic interpretation of theology was dramatically different than the interpretive methods practiced earlier in monasteries and cathedral chapters – based on lectio divina using ruminative and meditative reading.

Scholastic Theology required a comprehensive education in the logical analysis of Aristotelian philosophy. It was tantamount to moving the analysis of scripture from the heart to the head.

In addition many of the university faculty in the theological departments were Friars of either the Dominicans or the Franciscan orders of mendicants – and they differed in how rigorously to apply the philosophical analysis.

Scholastic Theology – Two Intellectual Leaders

Dominicans – Thomas Aquinas. Throughly rigorous in applying Aristotelian logic and argument to scriptural interpretation. His “Summa Theologiae” is now considered the gold standard in Catholic theology, despite at one time being condemned by the church.

John Duns Scotus (Franciscan). Oxford and Paris. He sought a middle ground between Aristotelian and Augustinian thought.

In the final analysis Scholastic theology became the standard for Catholics, and was roundly criticized by Protestants such as Luther. Both Luther and Calvin tended to lean heavily on Augustine in their analysis of scripture and doctrine.