History of the Bible

Types of Jewish Scripture

History of the Bible Lesson 3

Types of Jewish Scripture

We left off last week giving the best scholarly guesses as to the origins of the compositions of the TaNaK or Hebrew Bible. At the stage we were describing them they had not reached a fully fixed state. And we know little about how well they were accepted as the official compositions of the Jews.

In the 1st century C.E., we catch a glimpse of the Jewish Bible as the central symbol of Jews throughout the world, yet also as diverse in its forms and in its interpretations as Judaism was itself diverse and even divided in its response to Hellenistic culture and Roman rule. Different groups of Jews disagreed on what books constituted Scripture. They read their texts in different languages: While the Hebrew text was read by many in Palestine, other Jews both in Palestine and in the Diaspora read Scripture in Greek. Distinct lines of biblical interpretations also developed in this period. An examination of the Bible at Qumran (in the Dead Sea Scrolls) reveals some of the complexity.

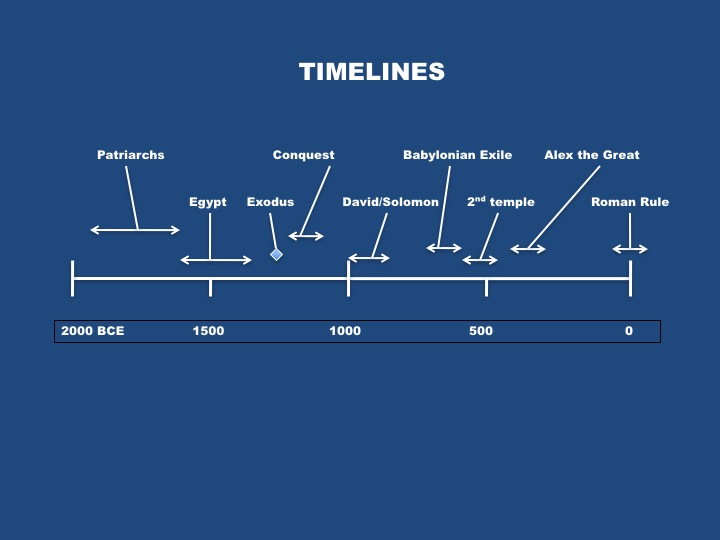

Let’s look at the timelines again as a reminder of what we said last week.

Timelines

Here is the somewhat complex picture I drew last week. What we concluded was that the compositions came from a rich oral tradition of the people of Israel that stretched over a thousand years and that this oral tradition was written down in two brief periods in which the people of Israel had a stable court bureaucracy in place. That would be this period labeled as David/Solomon, which was the era of the first temple. And this period labeled 2nd temple. But again, we do not know a lot about how the Jewish people used this literature and which parts of it they used. So today we will fast forward a few more centuries to the period labeled as Roman rule, which coincides with the beginning of the Christian movement.

Because here, for the first time, we get a real

historical glimpse of how these compositions were being used and by whom.

Types of Jewish Scripture

So our discussion for today is called The Types of Jewish Scripture. And the reason this period has become such a good source for understanding is that it is a period in which we have found a great deal of written Jewish literature.

And this literature happens to be focused to a large extent on those scriptures in the TaNaK. So we have a somewhat circular process going on here. We read this literature that is interpreting those scriptures in order to interpret what the writers of of this literature thought of those scriptures. Before, all we had was those scriptures – now we have a first glimpse of what the Jews thought of those scriptures. And what the Jews of that era thought of those scriptures may surprise you.

And what we learn from this literature is that in this time period Judaism was simultaneously distinctly unified and at the same time internally divided. To an outsider, a Gentile, there was no other people so unified, an extended family, despite being scattered all over the Mediterranean world. They were considered almost a second race among the world’s people. But from the inside ,they were almost at each others throats. And they held widely differing views about TaNaK.

The “Torah” Concept

As we have learned before in our year long Torah cycle, the word Torah has many connotations in Jewish thought.

The term Torah can stand as a central symbol that unified Jews throughout the Mediterranean world.

Torah signifies a shared set of texts that are read in worship and study, above all, the Law of Moses.

Torah connotes a shared story as well found within those texts, a story that provides all Jews with a sense of identity among the nations.

Torah means also a set of fundamental convictions, especially that God is One, that God has elected the people Israel, and that God and Israel are bound by covenant.

Torah contains the commandments that spell out the demands of covenant on the side of the people, and Jews everywhere were linked by shared observance of circumcision, the Sabbath, and other moral and ritual obligations.

Torah also provides the basis for a

wisdom, or philosophy of life, based on the covenant and commandments.

Torah as a Source of Contention

But in 1st century Judaism if Torah is a symbol of unity; it was also a source of contention among competing groups.

There was not firm agreement on what actually constituted Torah -which writings were to be regarded as Scripture.

The Samaritans, centered in their temple at Shechem, and the Sadducees, centered in the national temple in Jerusalem, each recognized only the five books of Moses as authoritative and based their beliefs and practices on Torah in the narrowest sense.

In Alexandria, the Hellenistic Jew Philo also seemed to focus almost exclusively on the first five books in his extensive writings, although he was aware of the Prophets and other writings.

At Qumran, the Essene sect recognized and commented extensively on both the Law and the Prophets but also collected and wrote a number of apocryphal texts of their own.

The Pharisees seem to have had the most

inclusive sense of Scripture, including Torah, the Prophets, and the

Writings, as well as their distinctive understanding of Oral Torah (continuing

interpretation).

The Diversity of Judaism

Jews in the Mediterranean world of the 1st century C.E. were diverse and, sometimes, divided.

The first way Jews were divided was geographically. As a result of all of the turmoil in the Jewish homeland over many centuries there were multiple instances of Jews leaving Israel and not returning. Sometimes voluntarily, sometimes through force. By the first century there were approximately 2 million Jews in Israel and over 5 million in the Diaspora. The Diaspora simply means any place other than Israel. Not highly dispersed, but in urban centers. Some of the larger ones were in Alexandria in Egypt, Rome, in present day Italy, Duro Europa in Babylon, and Athens in present day Greece. Geographically, more Jews lived in the Diaspora than in Palestine. Most of the Jews lived in urban centers rather than the countryside, where they could form larger communities to practice a more holy life separate from the surrounding pagan culture.

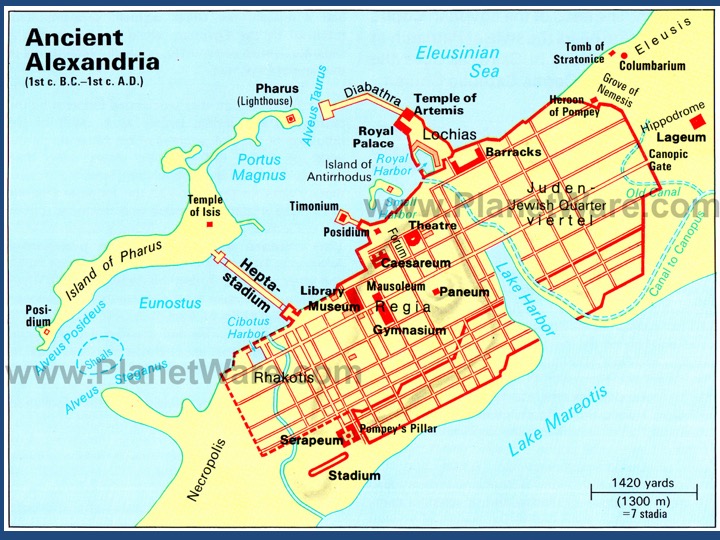

This map illustrates the widespread nature of the Jewish Diaspora. Again, many more Jews lived in the Diaspora than in present day Israel. The largest concentrations were in Alexandria, Damascus, Antioch, and Rome. Alexandria represents an important and impressive Jewish population in the Diaspora. See the map below.

This is a 1st century map of Alexandria in Egypt. When Alexander the Great took Egypt he paid special attention to Alexandria, building many important edifices, including the Gymnasium for education in Greek culture, theaters and Museums, as well as a Royal Palace and a magnificent temple to the pagan goddess Artemis. Then he named the city after his favorite person in the world - himself.

But note the very large Jewish Quarter on the eastern side of the city. This was separate and consisted almost entirely of Jews.

Alexandria was the home of Philo, the famous Jewish philosopher of the first century.

Further Diversity

Linguistically, Jews in the Diaspora predominantly spoke Greek (in the west) or Aramaic (in the east), whereas in Palestine, Hebrew and Aramaic dominated, although Greek was widespread as well.

Culturally, Jews in the Diaspora were a tiny minority among pagan neighbors, whereas in Israel, Jews were an oppressed majority. And the Roman Empire had a consistent strategy on how to handle problems from a major majority. They did it by breaking things and killing people.

The most important divisive factors were ideological: Jews disagreed on how to respond to the aggressive cultural challenge posed by Greco-Roman culture and Roman imperial rule. In Palestine, Jewish sects (the Sadducees, Pharisees, Essenes, Zealots) had political, as well as religious, differences.

This combination of factors generated a large amount of literature in both Hebrew and Greek that forms the basis, together with archaeological information, of our knowledge.

Diversity in Scripture

Diversity also appears in the version of Scripture used by Jews.

In the western Diaspora, the Hebrew text had been translated into Greek already by 250 B.C.E. This translation was regarded as divinely inspired by Hellenistic Jews, who exclusively used the LXX, perhaps little aware of the differences between the Greek and Hebrew.

In Palestine, Hebrew seemed to have been exclusively used in synagogue worship and in study. The appearance of Aramaic Targums (highly interpretive translations of the Hebrew), however, suggests that Hebrew was not familiar to many worshiping Jews even in Israel.

Diversity in Interpretation

Jews in the 1st century also interpreted their Scripture from distinctive perspectives.

Our knowledge on this point (as on others) is selective and based on the extant literature: We may suspect that the Zealots, for example, interpreted Torah from their perspective, but we don't have evidence of that.

Philo of Alexandria read the LXX in the manner of a Greek philosopher, seeking moral instruction and interpreting difficult passages allegorically in order to find a deeper wisdom.

Pharisees used midrash (from Hebrew darash = "seek") as a way of contemporizing ancient written commandments to new circumstances in accord with their commitment to a life of purity.

The Qumran sect interpreted the Hebrew text from the perspective of their sectarian identity as a community of the pure, formed and instructed by the Teacher of Righteousness, using pesher interpretation to apply all of Scripture to the life of their community.

Dead Sea Scrolls

And before we conclude I want to emphasize briefly the importance of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran (the Essenes) and subsequent archaeological and literary study is of foremost importance for the knowledge of the Hebrew Bible in the 1st century.

Among the compositions were many biblical manuscripts in Hebrew, the oldest extant witnesses to the text.

The numbers of copies of certain compositions suggest the importance they held for the community. There were copies of almost every book of today's jewish Bible in the Collection. There were many copies of the Torah. And several of the book of Isaiah, indicating a possible higher appreciation of that book.

Comparing biblical compositions to the LXX and to later standard versions of the Hebrew (the Masoretic text) indicates a highly fluid textual situation.

The sect's practice of collecting (e.g., the Book of Jubilees) and writing biblical apocrypha (e.g., the Genesis Apocrypha) suggests simultaneously the central position of Torah and its malleability.

The same combination is found in Qumran's sectarian mode of interpretation: Torah is all important, but it is also read in light of contemporary experience.

These Essene interpretations are

remarkably similar to another Jewish sect’s interpretations – the Christians.

In conclusion, in the first century the TaNaK was fairly well defined. But as you can see from our discussion there was no consensus with the Jewish community as to which parts of it were important other than the Torah.

That consensus would come later. It is interesting to note historically that the canon of TaNaK and the canon of the New Testament were pretty much decided at the same point in history.

Next Week:

The Birth of the New Testament canon.

We will now be making a shift away from our Old Testament to our New Testament.