History of the Bible Lesson 4

Birth of the Christian New Testament

History of the Bible Lesson 4

Birth of the Christian New Testament

By way of a quick refresher, for those of you who might have missed our introductory lesson in this series, let's briefly review the stages of Biblical history that we will be reviewing so yo can see where we are.

Lesson Stages

I. The origins of the biblical compositions and the process by which they reached the form of a collection within Judaism and Christianity.

II. The multiple versions of the Bible in antiquity and the patterns of interpretation thru the Middle Ages.

III. The multiple strands of the Bible’s story as a consequence of the Renaissance, Reformation, and Enlightenment.

IV. The Bible in modernity, with attention to the development of historical criticism and contemporary responses to it.

We are still in the first time period –covering the initial origins of the compositions that make up what we now call the Bible. Up until now we have covered the creation of the Hebrew Bible. Today we will cover the Birth of the Christian New Testament. And we will finish this first stage with a review of how both the Hebrew Bible and Christian Bible finally evolved into a collection, or canon.

One Jewish sect of the 1st century, which quickly

became a Gentile rather than a Jewish movement, also read the Jewish Bible in

its Greek form (the Septuagint), from a perspective established by the death

and resurrection of Jesus, whose followers called him Christ and Lord.

Christian writers engaged the Jewish Scripture in their effort to communicate

and understand the meaning of their own experiences and are legitimately

regarded as a form of sectarian Jewish interpretation. The 4 Gospels, 21

Letters, and 1 apocalyptic composition that comprise the earliest Christian

literature all seek to place Jesus and their experience of him within the

longer story of Israel, but do so in a manner that marks them as distinctive

and the start of an unanticipated sequel to that story. Indeed, the virtually

simultaneous birth of Christianity and the birth of the codex (a book instead of a scroll) will also give

distinctive shape to the Christian form of the Bible.

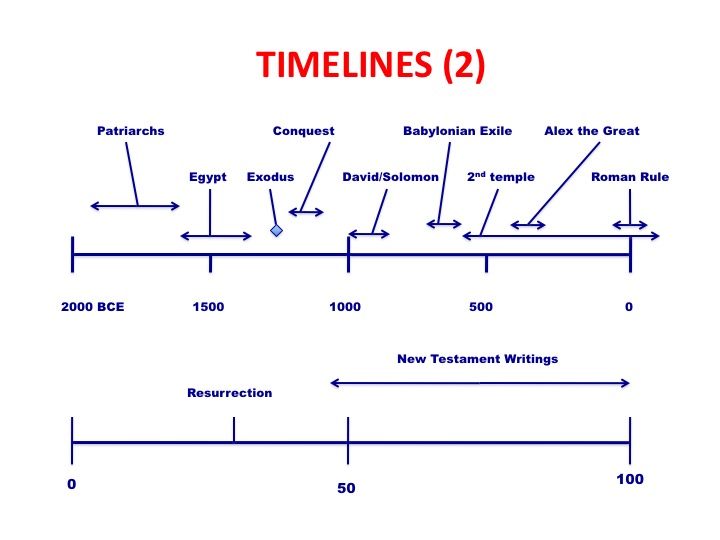

Let's first compare the timelines of the Hebrew Bible (old testament) and the New testament writings. We have already reviewed the top timeline, which covers approximately 15-20 centuries.

By contrast all of the writings that ended up in the New Testament were written in maybe 70 years. It is a remarkable literary production.

So - what other contrasts are there?

Contrasts

This literature is produced in

circumstances different than those that generated Torah.

In contrast to centuries of community life in ancient Israel, Christianity produced its formative literature within roughly 70 years.

In contrast to a literature formed out of the cult and court of a nation, the New Testament arose out of the religious claims of a Jewish sect.

In contrast to working in the Hebrew language, the New Testament was written entirely in Greek and interpreted the Greek Scriptures (LXX).

And in contrast to Torah, which remained and remains the text of the Jewish people, the New Testament everywhere reflects the inclusion of Gentiles.

And these writings had their own characteristics.

Characteristics

The writings undoubtedly emerged

from community experience, although there is even less confirming archaeological

evidence for earliest Christianity than for ancient Israel.

Both oral and scribal activities were involved in the process of composition, but it is not always possible to distinguish them.

The dating of compositions and the relationships among them are a matter of scholarly guesswork, with few external controls to provide certainty.

The rapid and prolific production of a body of literature suggests certain social dynamics in earliest Christianity, but even more, its place within a highly literary Jewish and Gentile world.

So, let's talk about what other differentiating factors were present.

Differentiating Factors

The fundamental starting point for the religion and for its reflection is the conviction that Jesus is Lord, not only resurrected from the dead but exalted to the status of God.

The fundamental issue that the first Christians needed to resolve was the manner of Jesus' death: Crucifixion created a cognitive dissonance with both Jewish and Greco-Roman ideas of how God works.

Not only the experience of the resurrection but the continuing experiences~both positive and negative-of believers within communities needed to be addressed and interpreted.

The framework for the interpretation

of Jesus and of the "New Creation" and "New Covenant" was

the text of the Septuagint (LXX), the Greek translation of Torah.

Authorship and Dating of the New Testament

Neither authorship nor dating of the New Testament books can be substantiated by examining the texts themselves.

The most “reliable sources” we have comes from the church fathers, the leaders of the church in the post-apostolic age. There is an unbroken chain of writers discussing the New Testament that goes back to soon after the Gospels were written. The writings of the church fathers are referred to as "the tradition" or as "patristic sources" in most discussions of this subject. So who are these "patristic sources". Well - they actually have names.

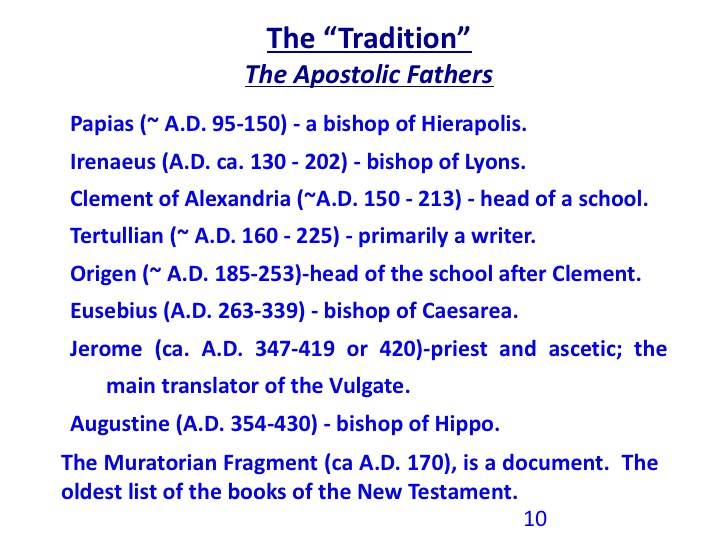

The “Tradition”

The Apostolic Fathers

Papias (late 1st cent. - mid 2nd cent.) was a bishop of Hierapolis. He wrote a five book series, Interpretations of the Sayings of the Lord, which has now been lost except for quotations in later books, which are referred to as the fragments of Papias.

Irenaeus (A.D. ca. 130 - ca. 202) was a bishop of Lyons. His preserved writings argue primarily against the Gnostics, a heretical splinter group. Because of the theme of this writing, he spent more time discussing sources than most writers of this era.

Clement of Alexandria (A.D. ca. 150 - ca. 213) was the head of the catechetical school in Alexandria. He should not be confused with Clement of Rome, one of the first popes.

Tertullian (A.D. ca. 160 - ca. 225) was primarily a writer of which many works are preserved. He converted to Christianity in middle life, but split away from the main church late in life largely because the church was not strict enough to suit him.

Origen (A.D. ca. 185 - ca. 253) was the head of the catechetical school in Alexandria after Clement. He left there as a result of a conflict (more political than theological) with the local bishop, and founded a new school in Caesarea.

Eusebius (A.D. 263-339) was bishop of Caesarea and the first true church historian. He preserved much of the tradition that would have been lost otherwise.

Jerome (ca. A.D. 347-419 or 420) was a priest and ascetic who moved frequently and wrote on many topics relevant to the church. He was the primary creator of the Vulgate, a key Latin translation of the Bible from Greek and Hebrew sources.

Augustine (A.D. 354-430) was a convert to Christianity and became bishop of Hippo. He was one of the great theologians of the church, and he also reported on historical details. In this time (and largely under the influence of Jerome and Augustine) there were several councils that ratified the contents of the current Roman Catholic Bible. As such, this is a natural time to end the discussion of the tradition. Practically speaking, the vast majority of the canon was accepted as soon as it was written, but there were several books with more controversial histories that took longer to accept or reject.

The Muratorian Fragment (ca A.D. 170) is not a church father, but a document. It is the oldest list of the books of the New Testament. The document itself is in bad shape (that's why it is labeled as a fragment), so for the most part it is difficult to interpret the absence of a particular book from this list. A book being on the list is a fair indication that it was in widespread use, however. It is dated because the author refers to the recent episcopate of Pius I of Rome, who died in A.D. 157.

The Fragment is very telling however. It lists 23 of the current 27 books of the New Testament. This seems to indicate that there may have already been rather broad agreement as to which books were being read in the next century after the completion of the writing of the New Testament composition.

Authorship and Dating of the New Testament (2)

Should we rely on the tradition or throw out the tradition and rely on careful examination of the texts?

Especially for the ancient tradition, we can expect that the church fathers actually had information that is not available to us by virtue of how close they were to the events themselves.

Textual criticism of the New Testament can be problematic because it lends itself very strongly to non-conclusive arguments that depend more on the assumptions of the critic than the text

The Gospels – Authorship

From examination of the texts themselves there is a predominant view that all four were anonymous.

The tradition (the patristic fathers) came down on the current common notion that the four authors were Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. And they tended to be precise about who they were. Matthew was the tax collector chosen by Jesus as one of his original disciples. Mark was John Mark, a traveling companion of Peter. Luke was Luke the physician, traveling companion of Paul, and John was John, son of Zebedee, an original disciple.

The Gospels – Dating and Sourcing

The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke show dramatic similarities. When displayed in three columns, with Matthew on the left, Mark in the middle, and Luke on the right, it becomes apparent that there is a significant relationship between the Gospels.

They frequently describe the same events, have events in the same order, and use the same wording in a way that implies written dependence rather than oral dependence.

Understanding the source of these similarities is referred to as the synoptic problem.

Synoptic is a Greek word meaning “seen together”.

The Gospels – Dating and Sourcing (2)

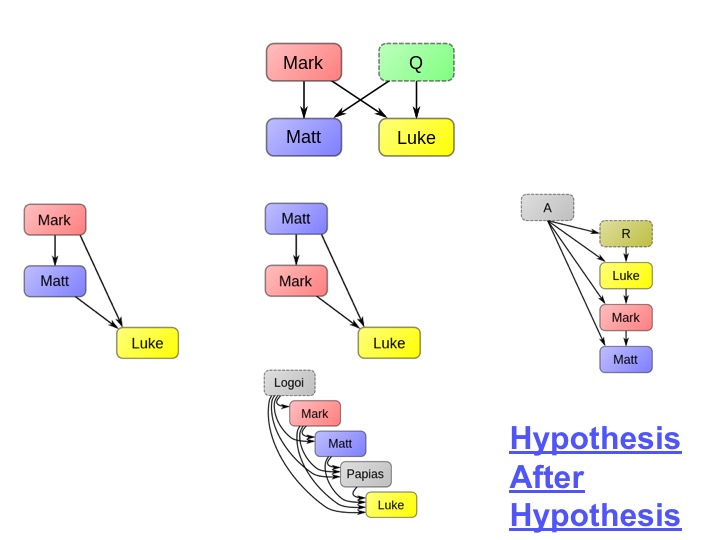

The dominant understanding is that Matthew and Luke both separately had access to Mark, but not to each other.

For passages that are in all three Gospels, Matthew agrees with Mark and Luke agrees with Mark much more than Matthew agrees with Luke.

Both Matthew and Luke agree with each other, however, on content that is not in Mark.

The understanding here is that there is another source, called Q by scholars, that both Matthew and Luke had. Q is primarily composed of sayings of Jesus.

As a footnote to this, Q is short for Quelle, a German word for "source". Q has never been found.

So this hypothesis became known as the "two-source" solution to the synoptic problem. There were two sources (Mark and Q), and Matthew and Luke copied from both of them, but not from each other.

So - were there more hypotheses that might be able to explain the relationships? I found about 20 of them. Here are a few:

The top one is the standard two source hypothesis. The others are just a few alternate hypothesis which are claimed to explain the synoptic problem.

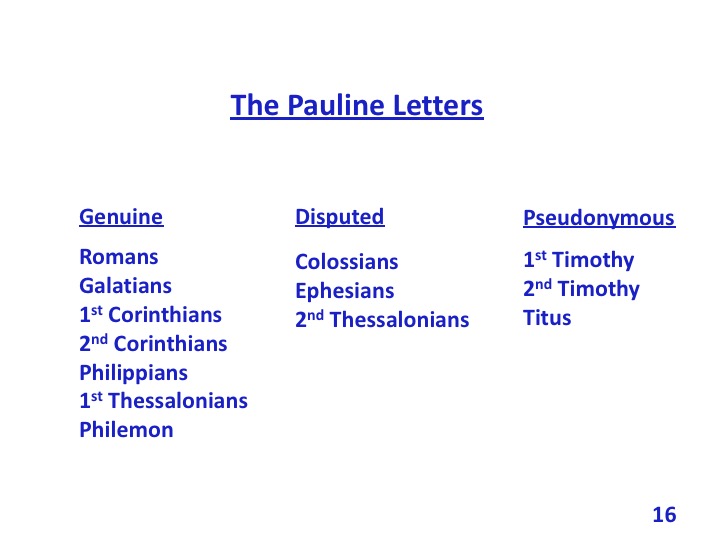

Authorship has always been a contentious subject among biblical scholars. One of the more common determinations of Paul's letters is shown here. Of his 13 epistles 7 are universally accepted as genuine - written or directly dictated by Paul. The next 3 are considered as disputed. This tends to mean they are letters probably written for Paul by one of his close associates, maybe with his approval, and then attributed to Paul. Pseudonymous means that these may also have been written by associates of Paul, but not with Paul's approval. But they claim Paul as author.

The Earliest Compositions - All Letters

In various ways and in a variety of literary genres, the first Christian writings sought to interpret the story of Jesus in the past, in the present (in the lives of believers), and in the future (in God's final triumph).

The earliest datable Christian compositions took the form of letters written by leaders of the movement to communities (ekklesia = "church").

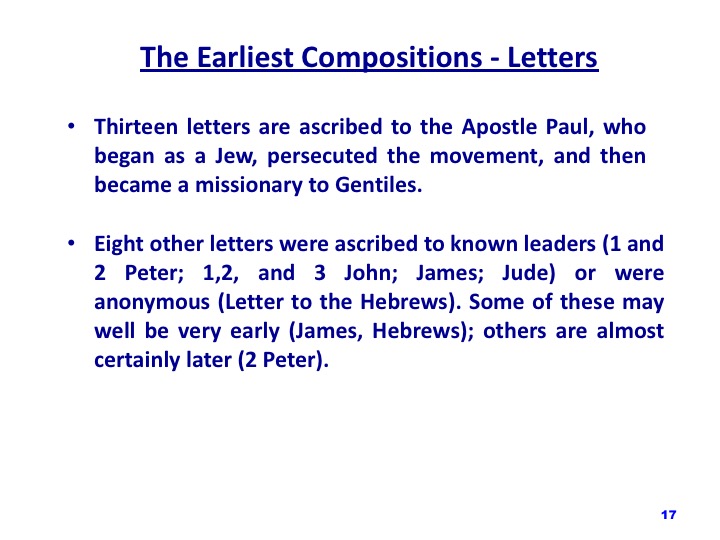

Thirteen letters are ascribed to the Apostle Paul, who began as a Jew, persecuted the movement, and then became a missionary to Gentiles. Seven letters (Romans, Galatians, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, Philemon) are certainly by Paul, while three (Colossians, Ephesians, 2 Thessalonians) are disputed, and three others (1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, Titus) are rejected by many scholars as pseudonymous.

Eight other letters were ascribed to known leaders (1 and 2 Peter; 1,2, and 3 John; James; Jude) or were anonymous (Letter to the Hebrews). Some of these may well be very early (James, Hebrews); others are almost certainly late (2 Peter).

Characteristic of these letters is a practical focus on the moral life of specific communities, an appreciation both for the death and resurrection of Jesus and his continuing presence, and in most, an intense engagement with the symbolic world of the Septuagint.

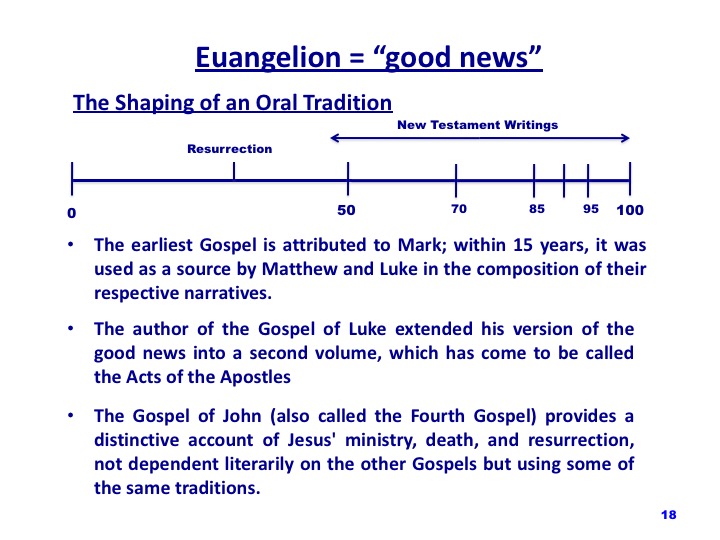

During the time when the earliest letters were being addressed to communities, the memory of Jesus was handed on in communities and, sometime around 70 C.E., began to be literarily shaped in the form of Gospels (euangelion = "good news").

The earliest Gospel is attributed to Mark; within 15 years, it was used as a source (together with another collection of sayings, called Q, and other materials) by Matthew and Luke in the composition of their respective narratives. The close literary relationship among Mark, Matthew, and Luke is expressed by the term Synoptic Gospels.

The author of the Gospel of Luke extended his version of the good news into a second volume, which has come to be called the Acts of the Apostles: It provides a selective and theologically weighted account of Christian beginnings with a particular focus on Peter and Paul.

Characteristic of the Gospels is the presentation of Jesus' ministry of teaching and wonder-working, his conflicts with religious authorities, and his death and resurrection. Implicit in the depiction of Jesus and his disciples (mathetai = "students"), however, is moral instruction of the readers. The Gospel of John (also called the Fourth Gospel) provides a distinctive account of Jesus' ministry, death, and resurrection, not dependent literarily on the other Gospels but using some of the same traditions.

The Book of Revelation, like its literary prototype, the Book of Daniel, is a mixed genre ofletters to the churches of Asia Minor (chapters 1-3) and heavenly visions by John the Seer (chapters 4-21), which assure readers that God's ultimate triumph in history is grounded in the exaltation of Jesus to God's throne.

Are There Other Writings?

There may well have been many more things written in the first generations that have been lost. There were certainly a great many things written in the first half of the 2nd century - and later.

Apostolic Fathers

•Shepherd of Hermes

•7 Letters of Ignatius

•2 Letters of Clements

•Didache

•Letter of Polycarp

“Competitive” Writings

•The Gnostic writings

•Acts of Peter

•Acts of Paul

•Gospel of James

•Gospel of Peter

•Gospel of Thomas

Many of the writings in the "competitive" group were considered completely heretical by the early church. Some of the those in the category of the Apostolic Fathers were favored by some of the "tradition" and were being considered for inclusion into the church's approved list.

Technological Changes

In the first of many technological changes that affect the story of the Bible, the New Testament compositions were predominantly written on the codex rather than the scroll.

Ancient "books," including those of the Jewish Scriptures, were written on scrolls, made up of papyrus or parchment and stitched together in rolls; writing could be on only one side, and texts were limited by the length of the scroll. Specific passages, furthermore, could be found only by "unscrolling."

The codex is a compilation of "pages" (usually of papyrus), folded and stitched together in quires to form a "book" in the proper sense. The codex was cheaper, more mobile, could contain more text, and allowed easier access to specific passages in a composition. The codex appears for the first time in the 1st and 2nd centuries C.E. and, from the first, is associated with Christian literature.

And in our next lesson we move on to the actual formation of the Jewish and Christian Canons.