This Religion Called Christianity 10

Mike Ervin

This Religion Christianity 10

Links

< Home Page > < This Religion - Christianity Menu > < Top of Page >

This Religion Called Christianity - the Text

Lesson Ten Christianity and Politics

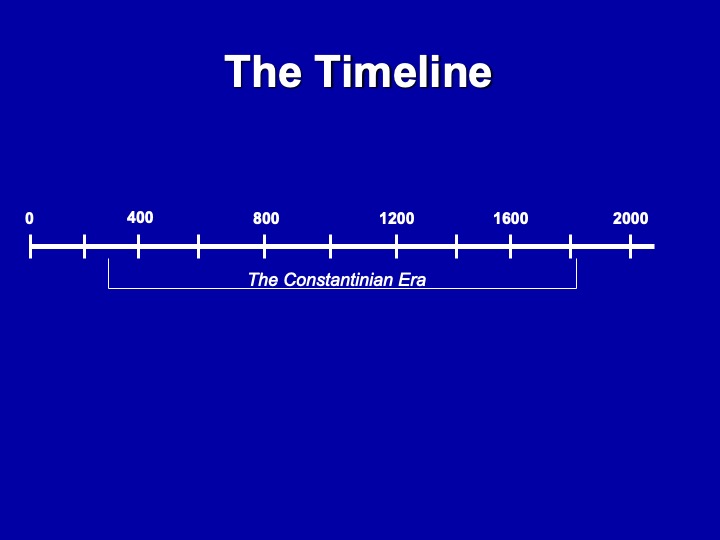

Scope: Christianity began as a minority intentional community that was socially marginalized and persecuted by imperial power. Over the centuries, it became closely associated with state power, and the shadow of the Constantinian era continues until today. In the East, Caesaro-Papism retains some appeal and influence. In the West, Christendom involved a constant negotiation between the worldly ambitions of the papacy and those of emperors and kings. After the Reformation, there were religious wars in Europe between Catholic and Protestant. In newly discovered lands, missionary competition was closely associated with colonialism. The political revolutions of the 18th through 20th centuries (the American, French, and Russian) ushered in the Post-Constantinian era, which poses fresh challenges to Christians.

Outline

I. One reason that Christianity is so seldom appreciated in strictly religious terms is that, for much of its existence, it has been deeply involved in politics and culture.

A. This is one of Christianity's many paradoxes, because it began life as a sect of Judaism that met resistance and persecution.

1. Jesus was executed by Roman authority as a messianic pretender.

2. Paul and other first-generation leaders were repeatedly imprisoned.

3. The tradition of martyrdom and of apologetic literature through Christianity's first centuries testify to its political powerlessness.

B. Christianity's initial focus-found in the New Testament-was on the shaping of an intentional community. It was ill-equipped to become the imperial religion.

1. In this respect, Christianity is distinct both from Judaism and Islam, whose systems of law had the shaping of a society in view from the beginning.

2. Remember the complexity of Christian moral teaching in the New Testament, and think of using the New Testament to guide the religious life of a civilization.

II. In 313, the Emperor Constantine convelied and established Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire; the "Constantinian era" has affected Christianity up to the present.

A.

1. Constantine's summoning of the Council of Nice a in 325 indicated the need to have a unified Christianity as the glue of society.

2. Under Theodosius I, the establishment of Christianity was complete, and both Judaism and Greco-Roman religions became severely disadvantaged.

B. In the East, the Constantinian connection took the form of Caesaro-Papism, in which there was a close cooperation between political and ecclesiastical authorities.

1. Such emperors as Leo and Justinian considered themselves theologians, as well as leaders of the state.

2. The "New Rome" held off the "infidels" (Muslims) for centuries in the name of Christ, until the final conquest of Constantinople in 1516.

C. In the West, the ascendancy of the pope made for a sharper distinction between political and religious authority, but tbe history of "Christendom" was one in which botb popes and kings tbought of themselves as servants of God.

D. The four crusades undertaken by European Christians to retake the Holy Land from Muslims represented the ideal of state/church collaboration. We should note several paradoxes of these crusades.

1. Christians, who in the beginning, proclaimed only a new heavenly Jerusalem and awaited the coming again of Jesus, were now involved in a real estate and trade venture, in conquering the Holy Land as a political and religious

2. The last and fourth crusade ended with Christian warriors sacking the city of Constantinople, which was a Christian city!

3. Christians today who are upset by the concept ofIslamic jihad should remember that the notion of a holy war (a crusade) is deeply ingrained in the Christian tradition.

E. Equally a manifestation of the Constantinian outlook is the Inquisition, a cooperative effort between the church and tbe state to establish uniformity. It tortured and sometimes killed heretics (and Jews), both for the sake of the church and the "Christian state"-to keep them pure.

F. The expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492 is another example of the profound affiliation of politics and religion in medieval Europe.

G. Even with the Reformation, the same assumed link between political and religious power continued on every side:

1. In European countries, the principle of cuius regio, eius religio ("whoever is prince, his is the religion") divided a continent into Catholic and Protestant countries that entered into long-lasting religious wars.

2. World exploration by European adventurers served the ends of ecclesiastical, as well as political, desires. A divided Christianity was transported to new lands, as mission and colonialism merged in a competition for souls and the importation of European culture as "Christian."

III. Since the 18th century, the Constantinian era has been challenged above all in the West through political revolutions.

A. The American, French, and Russian Revolutions each called into question the place of Christianity as a state religion.

1. In the United States, the "separation of church and state" removes the privilege of establishment without directly attacking Christianity or any other religion.

2. In France, a more aggressive revolt against the church in tbe name of secular ideals (that themselves took on religious coloration) continued the old struggle over property and power.

3. The Bolshevik Revolution in Russia took its stand on the explicit repudiation of, and systematic attempt to eradicate, all religion.

B. Christians today struggle to come to grips with the reversal in the religion's political fortunes.

1. Some Christians still consider the Constantinian arrangement the ideal and seek to assert Christian political power.

2. Others rejoice in the separation of the religion from political power and see it as a chance to recover some of the essential dimensions ofthe religion that its long political history tended to obscure.